Saying Goodbye To Jacob Riis Beach, Until Next Summer

At Jacob Riis beach, I feel less alone.

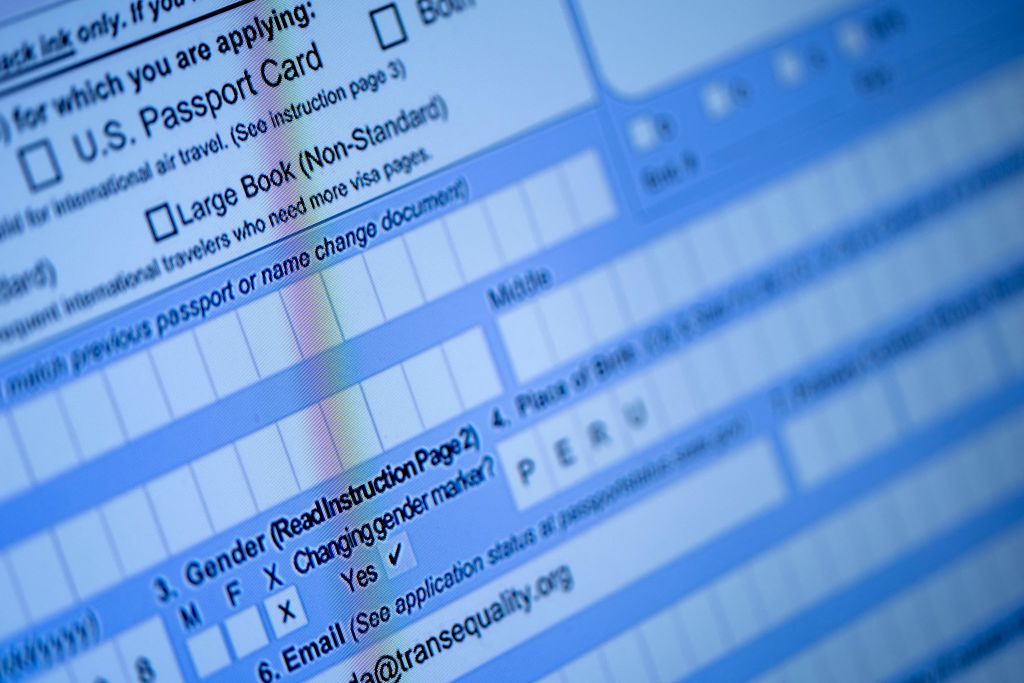

My first summer in New York was the summer I forgot how to be alone. I spent nearly every free Saturday traveling to Jacob Riis beach just to swim for a few hours and then commute back. Living in lower Westchester, “The People’s Beach” is a full two and a half hours away — train-to-train-to-ferry-to-shuttle — but I kept going back. Maybe it has something to do with the sealife instinct I am convinced that all trans women (weird mermaids, migratory maybe) develop. This instinct drove me to write continuously about them through the first year of my MFA — about gills and the gross, beautiful bodies of the sea.

In the wild, certain fish — salmon being the most well-known — return to their home waters by river and creek and fish-tube to mate. Sea turtles do it too, as does the bluefin tuna, which can grow to more than 300 pounds easily. The ocean is full of wonderful bodies.

I have found my body strange for a long time. That parasite called dysphoria has hung from me like a dorsal fin for years, but at Jacob Riis beach that summer, I didn’t feel that way. I didn’t feel like such a freakish fish. I didn’t feel so alone.

*

The first time Charlie — who is at all times my girlfriend and boyfriend and self-appointed partner — and I went to the Jacob Riis beach, we were just going out of curiosity. What was this famous queer beach really like? It was late May, one of those hot early summer days where anything seems better than sitting in an unairconditioned bedroom. So why not spend some time on the ferry, watching the Statue of Liberty and the Manhattan skyline fade away?

When we finally got there, we walked in through the old art-deco bathhouse courtyard, past the overpriced bar that sells cold beverages to all the hot bathers. We walked down along the shore and passed all kinds of people sitting on towels, listening to music, and reading. Meanwhile, in the water, people dove, splashed, floated, or fought the waves toward the sandbar. A few people walked by, boobs bare and penises in full view.

It was lovely, just nature and body. But at this point in the story, Charlie and I acted as the awkward voyeurs. Not ready enough to join, I stood there feeling so distinctly my skin, the awkward patch of coarse hair I missed on my chin. I was watching. I was all eyes.

We chose a space to spread our sheet on the far-left side of the beach by an abandoned civic building. (I’d later learn from the internet that it was, in fact, an old naval base.)

“How many people are having sex in there right now?” Charlie asked, pointing to the building.

“Seven,” we both agreed.

In front of us, there was a group of stunning sunbathers. Their genders were impossible to really tell, and it did not matter. They were drinking white wine and primping their hair and cuddling and taking pictures. I was thrilled. I was nervous. I was in love with them, with Charlie, with the whole scene. One of them pulled off a white button-up they had been wearing and darted into the sea, a pair of top surgery scars a glossy red on their chest.

That is when, suddenly, I felt comfortable. I took off my dress, unclasped my swimsuit top, and left it sitting in the sand. I let my little breasts feel the sunlight and salt for the first time, knowing there were others like me all around: undefined beach bodies having fun.

By the time we were done traversing the waves, picking up blue and orange and murky green shells, watching little white crabs the size of a fingernail spin their legs into secret sand tunnels — the sky was flooded with night. Charlie and I packed up our things and started back home. We slept as densely as the ocean floor all night.

*

I repeated this trip to Jacob Riis beach numerous times throughout the summer, always with other people. I was never alone. I was forgetting how to be alone, in a good way.

On the Fourth of July, Charlie and I brought Jancie, our Canadian friend, to celebrate this country the only way we knew how—with queers and immigrants, all of just desperately trying to find a way to stay here. When a cop walked up to us, we looked him dead in the eyes with our tits out and both wondered, “What the hell did we do?”

He looked at us sternly for a moment. Then he said, “Your PBR looks nice and cold, but you can’t drink it here.” Somehow, there was no fear in either of us. All over the beach, there was beer and liquor and weed, and no one had been hurt, no one had been given a ticket. So we just covered the labels with a sock, and the cop made his way to the next enclave. All-day he walked back and forth in the heat, and all I could think about it was, “This what it’s like to feel safe and free in your body.”

I know that it is a blessing to have the body I have, that my whiteness and passability are qualities that protect me. The people that pose the biggest threat to me are cishet men and myself. But Jacob Riis, for the most part, feels especially safe because of the community. Allow me this naiveté.

*

My next beach visit was on a weekday. I had some time off and arranged with Charlie to meet at our usual spot; they could catch the ferry when they got done at work. So, I packed a book and headphones. I was ready to be alone.

At the pier, the line to board was quickly moving off the dock. I was running to catch it when I heard a familiar voice behind me call, “Brynn!” It was a poet friend of mine from college, Milly, and her girlfriend Erika.

“Are you going to the beach!?” Millie and I howled in unison at each other

“The gay beach!”

“Of course!”

That we should be so synced up was a miracle. They had missed the ferry an hour before and went to get lunch — an expensive salad with olives and the kind of dressing where, even if you could remember the name, you’d never be able to pronounce all the oils, spices, and sweetnesses that comprised it. From my bag, I supplied some wine I had been saving, and we drank and traded forkfuls of salad the whole way.

When we got there, we all laid out our towels, and I ran into Ophelia — a darling brief fling of my ex-girlfriend over whose neediness we bonded. Ophelia is another one of those trans women who had to forsake the sea when her body was changing, but here, it was amazing to see her feeling so free. We posed and took pictures, all salt, skin, and hair. When Charlie found us, we were drunk in the sand and our bodies were extensions of the coast — unimaginable until you see it in person, and then you never forget.

*

But the nature of the beach isn’t always accommodating. It isn’t always nice and scenic, doesn’t always even offer safe swimming.

There was the time Charlie and I went down without accounting for the summer rainstorm two days before. The rain had washed all the sewage and garbage out into the water. It was a hot August day, and maybe I should have noticed that no one was swimming before I took off my top and rushed into the water. Maybe I should have heard the chants of “No, no, no, no, don’t,” and the lifeguard’s whistle, but I didn’t. I dove right in and felt contaminated for weeks.

And then there was the time I went with my mom. She was a champion swimmer in her youth, and she wanted to see where I always swam. When we got there, thick gray clouds had gathered and were beginning to clap the sea with lightning. Just when we’d been there for long enough to be embarrassed by each other’s music choices and shocked in the way you are when you see your mother or daughter’s body and recognize that they really are a person too, we had to run to catch the first bus home.

*

My final trip to Jacob Riis beach was on the last day of the season. I was at work and kept talking about how much I was going to miss it until my boss finally said, “It’s slow. You can just go.” So I went.

I was content on the ferry, even though I had forgotten a hair tie and the wind whipped my hair all around my face. A girl, sitting with a boy on the other side of the deck, got up and brought me a scrunchie. “It looked like you needed one,” she said, and then walked back to her seat. I started reading a book and looked out over the water, glad for once to be alone — surprised I still knew how to be, but it didn’t last.

A deckhand came over to me. Sneakily at first, he pretended to examine the lifejacket container, then the conditioner of the wires, and then finally he asked, “Why are you alone?”

Because I could be, and I want to go to Jacob Riis beach one more time this summer. I hadn’t forgotten how.

It had only been two weeks since I had last been out there, but the landscape had changed so drastically. The tide had worn away about four feet of sand, leaving a wall between the waves which crashed more violently than I had ever seen before. There were only a few of us weirdos out there: a man painting waves on his hand and trying to capture a picture of them blending in, two other dykes making out in the sand, and a man juggling in a thong.

It was cold. Too cold to take my dress off. Too cold to swim. But I walked along the beach for a few hours and thought about what a summer it had been. How happy I was. How I finally found a place to match my body.