My hair is shorter now than it has been in years — an awkward kind of quarantine haircut. As I look toward a horizon of arches, an outline of ascending figures, and oil-paint blue and peach, I feel my hair pinned annoyingly tight behind my cloth mask. This view is very different from the one I have seen every day for the last six months while sheltering in place in my apartment: the dull cornsilk-toned siding of the two-story house across the street, occasionally the woman who lives there unloading her groceries, and many squirrels running along the phone lines (for some reason they always seem to run north). Looking at buildings has become a staple COVID-19 activity. Unable to enter places, I look at them. I go on date-day walks around Manhattan with my partner, Charlie. I text pictures of windows to a friend I have not seen in months. But now, back at the newly reopened Museum of Modern Art on 53rd Street, some things feel strange. For one, the absence of a crowd. For another, your temperature is taken at the door. Other than that, the dominant sense is a kind of tenuous hope bound up in the slow cynicism of reopening as Charlie and I look at Sonja Sekula’s “The Town of the Poor” (1951).

In pre-pandemic times, I would come to the MoMA often — three times a month sometimes. It is one of my favorite places to go on dates; there’s something erotic about looking and not being able to touch. I have seen “The Town of the Poor” many times before. It is a dense depiction of a city largely shaped by bridge-like gray lines and calligraphic traces, a barely decipherable writing. If you are deliberate, you can see what looks like mice, people walking down the street, windows, buildings, even hallways and — my partner says — our bedroom. It’s a cityscape few have ever seen in life, but now it seems all the more familiar. It’s a collision of interior and exterior. It is a painting full of forms — architectural, animal, human — and yet no form is entirely legible. Every body is a sketch, and every building is a blueprint. The exhibit quotes Sekula: “Looking outside my window, I think of all the contemporary American poets and artists who represent their outlook on this strange country and I find myself beginning to realize that I shall be one of them. I shall begin to speak of … a future that we begin to feel underneath the current of war and strife and uncertainty.”

“The Town of the Poor” is a projection, a wish, and an outline, a plan for space with room for deviation. What Sonja didn’t know was that she was at the height of a career that would be cut short by the combined pressures of misogyny, homophobia, and ableism. And maybe, I say to Charlie, that ignorance was a kind of short-lived blessing. Every morning we wake up in a nervous country and walk around the structures we know too well are impermanent.

Sonja Sekula was born in Switzerland in 1918 to well-off parents. When she was 17, she met and fell in love with the photojournalist and writer (and notoriously androgynous bad-girl who looked very hot in pleated pants, a Weimer-style gay) Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Their relationship was short-lived because the Sekula family moved to New York and Sonja enrolled at Sarah Lawrence College to study art. The following year, Sonja attempted suicide and was hospitalized. Of her 45 years alive, she would spend nearly a fourth of them in institutions.

This is where it gets hard to know who Sonja Sekula was, what the city and the suburbs looked like to her, what was going on in her head. One account tells of her walking down the street, convinced she was Jesus. Richard G. Mann, professor of art at San Francisco State University, writes that, during the era of her hospitalizations, “many leading psychologists considered lesbianism a symptom of profound mental disorder. … Her doctors repeatedly tried to ‘cure’ her of her sexual orientation, which they regarded as a debilitating manifestation of schizophrenia.” In her diary, Sekula wrote, “Let homosexuality be forgiven … for most often she did not sin against nature but tried to be true to the law of her own. To feel guilt about having loved your own kind body and soul is hopeless.”

Last year, I was at Sarah Lawrence College and took a class with the poet CAConrad. It was, in my memory, a hot autumn day early in the semester and full of the gradual chaos of the changing season. Students were lost around campus, wasps that had made their way indoors were diving against windows trying to get out. “Hope,” CA said, “is a scary word. If you are saying hope more than three times a day, there’s a crisis.” Looking back on it now, I realize that was one of the most stable points of my life. I failed to imagine that I would leave graduate school at all, that those tables would be replaced by windows of another kind. Crisis seemed so far away. Hope was a sentiment I remembered and was fortunate not to feel.

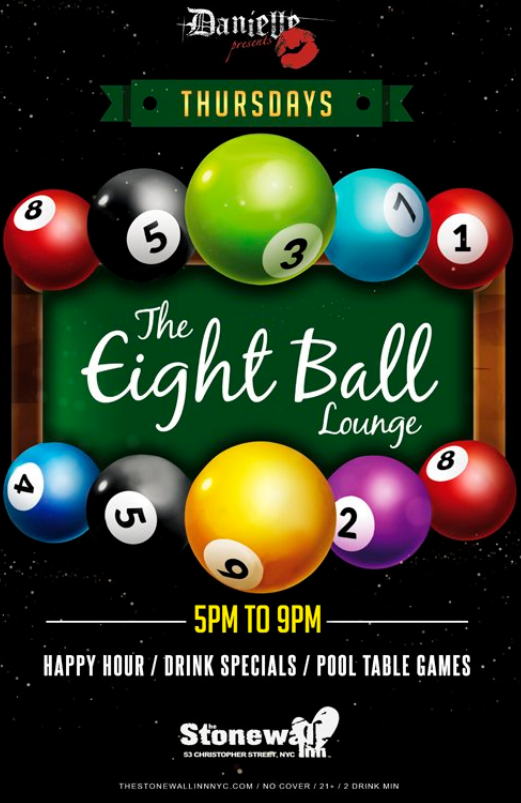

At the time of “The Town of the Poor,” hope was Sekula’s main resource. She had embraced her sexuality and was out proudly to the extent possible in 1951 New York. She lived with John Cage and Merce Cunningham — who were themselves lovers — and she finally experienced the success that the other abstract expressionists circumambulating down Monroe Street had.

Her paintings were featured in a group show at Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of This Century” Gallery and in three solo exhibitions. For a few years, she had been a regular contributor to shows at Betty Parsons Gallery. Her inclusion, as it turns out, was a bit of a controversy. Not long after her arrival, the men at Parsons, including Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, began to complain that there were too many unknown artists — “many of them amateurs, most of them women” — and left for male-operated galleries. While her work was attracting attention, it didn’t receive the acclaim of male artists. Her work was too small, often less than one square foot, and too varied to form a marketable brand. In 1951, shortly after their departure, Sonja suffered from another breakdown from which her career would never recover.

For the next 12 years, the frequency of her hospitalizations became more common, and she “lost the confidence to paint.” At one point in her diary, she attests to the reason for her frequent stays and writes: “I have enough experiences, also religious ‘visions’” — the scare quotes are her own — “which made my own family turn me to a sanatorium believing I was ‘sick’ when often all I was was being true to my mystically inclined nature.”

What strikes me now about “The Town of the Poor” is how dense and dark the lower left is, how much like a nighttime street-scene it is — infrequent yellows, a round window or a moon — and how bright the canvas becomes as it stretches up. This is one of Sonja’s largest works, if not the largest, and the most fun. Hidden in the vast crowd of spaces, there is a man in a funny hat and four people around a round table. It is so easy to lose them — to get caught up in the precarious patterns, sloping bridges, and shadows — but coming back to the painting after all these months apart, Charlie and I find them all over again. I recall another quote of Sonja’s: “Maybe a fire will come, maybe a war, maybe death or loss of mind, but today was good.”