The first thing you should know about this Prussian women’s boarding school: You’ll find more lingering glances within its walls than at a Smith College library on a Friday night.

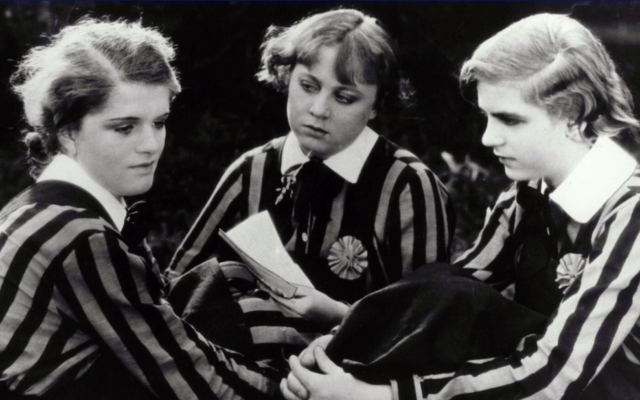

After her mother dies, grieving teenager Manuela (Hertha Thiele) is sent to aforementioned boarding school for daughters of Prussian soldiers in Northern Germany. She is heartily welcomed by a posse of endearing and occasionally mischievous girls. They make it clear from the onset: they are enamored with their governess Fräulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck). “Almost all the girls here have a crush on Miss von Bernburg.” Soon, Manuela, too, is stricken by infatuation (as evidenced by the hazy close-ups best achieved with a dab of petroleum jelly on the lens). While the girls embody a spirit of playfulness, warmth and to some extent, rebellion, the atmosphere is stingy on kindness under the oppressive watch of the headmistress (Emile Unda). Discipline rules. Chocolates are verboten. And God help the girl who tries to smuggle out a letter to parents decrying Sunday’s lack of food.

Mädchen in Uniform (Germany, 1931) was directed by Leontine Sagan, based on the 1930 play Gestern und heute (Yesterday and Today) by Christa Winsloe.

The subject of girl-on-girl desire is treated with a normalcy that might surprise the modern theatergoer, given the puritanism that has gripped swaths of the U.S., since, well the Puritans. But the film was made at a time when Germany enjoyed more artistic freedom under the liberal government of the Weimar Republic, which held sway from the end of WWI in 1918 until the cementing of Hitler’s dictatorship in 1933.

The movie played at Film Forum this weekend – the first of three showings as part of the SAPPH-O-RAMA Film Fest. In one memorable scene, students with rapturous expressions kneel at the ends of their beds, waiting for Governess Fräulein von Bernburg. To their giddy delight, von Bernburg makes her rounds with a kiss to each forehead. You would think a Manhattan audience has seen it all, and would be unfazed. But as anticipation mounts, when it’s Manuela’s turn, the full on affection reserved by Governess von Bernburg for her student draws a sizable gasp and awkward laughter from the house.

“I loved it!” says Sarah Cowan, 36, a video producer from Brooklyn.

“The whole scene was really funny, but also hot, because these kids are so repressed,” adds fellow film-goer Ainara Tiefenthäler, 33, a Brooklyn journalist. Ainara happens to be German and also notes the gender-neutral aspect of some of the language.

The sub-titles refer to “girls” [“Mädchen”], but the spoken German in the film is actually a gender-neutral “the children” [“die Kinder”]. With regard to the bedtime scene, “…that’s what I thought was interesting about the gender neutral language,” Ainara says. They use the words “the child” in the film. “But these are teenagers. They’re young women. They have desires that they’re living up through this fantasy. And it becomes so clear in that scene, because they’re all just smitten.”

“But also if that was a movie now [in the US], or if that was a scene now, that would be banned – or people would try to ban it.”

In its day, the film was initially well-received and garnered excellent reviews.

“This all-woman film from Germany is more than a curiosity and a worthy artistic achievement. It is a cinema phenomenon…Its memory will be for a long time a clearly defined emotion – that is the personal reaction of this hack”, wrote Edgar Hay, The Miami Herald, 1933.

“It’s rare to see a movie that’s almost 100 years old, and people are still laughing and engaging in this way,” Ainara tells GO. “And it’s not even an American movie, so the cultural context is completely different.”

The happenings in the film reflect the real-world rise of authoritarianism. Governess von Bernburg “has ideas that are clearly considered progressive in the school,” Sarah comments of an atmosphere that is all about grooming girls to become mothers of the soldiers that will fight for Germany. “The dynamic with the headmistress and then the other teachers or governesses – you get the sense that they disagree with her authoritarian practices but they don’t say anything,” Sarah notices.

Ainara’s take: “The governess is just wanting them to grow into fully rounded happy humans.”

After a school play put on to honor the headmistress, the girls drink a pungent, and clearly fermented, punch. Manuela creates a scandal in her tipsy state, loudly declaring her love for the governess. She is punished with isolation in “the sick room”. Students and teachers are forbidden to speak with her. But Governess von Bernburg breaks from the edict to try to offer comfort. Their bond is real, but the love must not be allowed to blossom.

A doom takes over the school, which soon turns to hysteria and terror when Manuela can’t be found. We see her begin to ascend a tall winding staircase. Her classmates ring the bell in alarm and frantically call her name.

The Film Forum audience groaned with worry. Would this be another lesbian film with a tragic ending? “But it’s also beautiful how all the girls come together and save her because I feel like we all know so many movies where the kid gets bullied… here she clearly gets bullied by authorities, but her peers come and embrace her,” says Ainara.

Several years after its release, Mädchen in Uniform was banned by the Nazi’s, specifically by Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Propaganda. He ordered all copies of the “degenerate” film burned. He also didn’t like the hints that authoritarianism sucks. Director Leontine Sagan fled for her life and playwright Christa Winsloe left Germany with lover Dorothy Thompson, the first American journalist to be expelled from Nazi Germany in 1934. Some of the cast and crew were Jewish, and met their demise in concentration camps.

Actor Hertha Thiele stood up to Goebbels when asked to appear in Nazi propaganda: “I don’t blow with the wind each time it changes directions.” She was blacklisted, left for Switzerland and lived to age 76.

Some prints remained in Romania where a “longstockings and kissing” cult reportedly existed among Bucharest schoolgirls, no doubt helping ensure that the film survived. It was almost banned in the U.S., but got a limited release because Eleanor Roosevelt liked it.

The film is “still is powerful, I think. It’s a different audience, certainly younger,” says West Village-resident, Regina, age 73. She saw it this past weekend and remembers seeing it 50 years ago in a lesbian coffee house. “The little bit of shame in our lives is less, certainly for a younger audience than it was for me when I was in my twenties.” Now more savvy about filmmaking itself, she appreciates the use of shadow and light, the black and white, and the quality of the production. “It still holds up. I think it’s a remarkable film.”

Mädchen in Uniform will hold additional screenings at Film Forum’s SAPPH-O-RAMA Film Festival on Tuesday, February 6 at 4:10pm, and Saturday, February 10 at 12:15pm

What Do You Think?

One comment on “Mädchen in Uniform Is Unexpectedly Timeless”

the only thing i’ll disagree with here is the “unexpectedly”. I actually screened this in a college course. once you watch it, you know exactly why it has endured. makes my little lezzie heart so happy for it to get the kudos it deserves…. campy, sincerely, or a little of both.