Coming out means different things to different people.

Donna Sue Johnson self-identifies as a “big Black beautiful bohemian Buddhist butch.” She first started coming out as a lesbian to herself when she was a lieutenant in the Air Force in 1980. “Which is kind of precarious, especially in those days, because there were a lot of witch hunts in the service, trying to weed out the LGBTQ crowd and dishonorably discharge them,” she tells GO.

But it was the San Francisco Pride parade in 1980 that saved Johnson and gave her the resounding affirmation she needed so she could live her true, authentic life.

Coming out was a moment of empowerment for Johnson—but she recognizes the challenges many LGBTQ people face when they come out to their community, family, and the world at large. While her family had an initial response of disappointment, it was temporary.

National Coming Day, coined by queer activists Robert Eichberg, his partner William Gamble, and Jean O’Leary—has come to shift over the years. It began as a positive effort to urge LGBTQ people to come out and allow everyone else to see queer existence and break down stereotypes and fears about LGBTQ people. As acceptance and tolerance for LGBTQ people have grown, the experience of coming out has morphed into something that many of us feel obliged to do, or want to do, in order to have a valid queer experience. Because straightness and cis-ness are still assumed until we announce to friends and family our truths, there is a sense of urgency around coming out.

GO wanted to connect with generations past and present about what it means to come out in a world not built for the safety of LGBTQ people. Does coming out give us more freedom to thrive? Or is it something we feel pressured to do by living in a cis-heteronormative culture? Or is it both of these things all at once?

At 62 years old, Johnson still believes that coming out is an important process for LGBTQ people, but wonders who exactly it’s for. Queer and trans people are sometimes made to feel like they need to come out because they’re automatically “othered” living in a cis-heteronormative world. While some queer and trans folks who “pass” as straight or cisgender face the constant annoyance of coming out to feel valid in their identity, others who may not have this passing privilege are outed without their consent by not conforming to what this cis-heteronormative world expects from gender presentation.

“Normal is only a setting on a washing machine. What’s really normal? You know what I mean? But I do feel that it’s important to come out,” Johnson tells GO.

The notion of coming out as LGBTQ, at first, wasn’t about making an announcement about sexuality or gender identity for straight or cisgender people. It was actually all about coming out into gay culture. Which Joyce Banks, a 74-year-old lesbian, confirms when telling the story of coming out in 1961. “I’m a World War II baby. You just didn’t come out and parade yourself,” she tells GO. “You stayed in the closet until you got with people who felt the same way you did.”

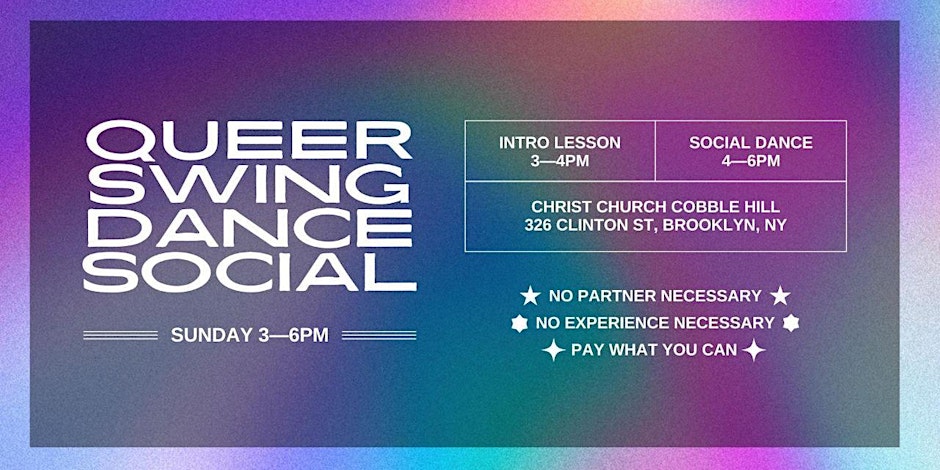

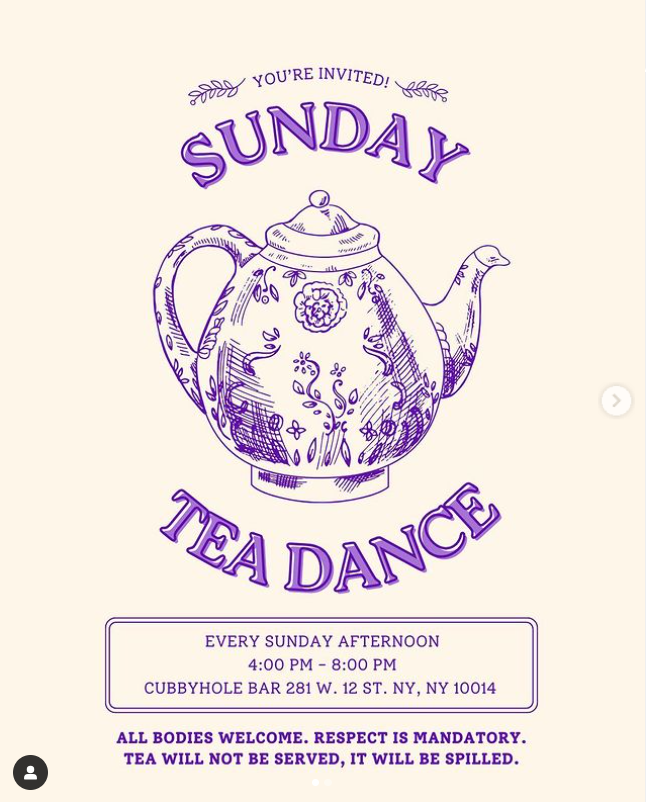

Banks recalls gatherings at some of the first gay bars in NYC back in the day: how they’d get raided by police, and how men and women had to be wearing at least three items of clothing associated to their assigned sex, otherwise they’d be arrested, or worse. Banks likened coming out in the 60s to playing poker, saying, “You don’t show all of your hand, you just show some of it until you know how someone perceives you.” And while she believes the worst is over, as LGBTQ people don’t have to hide the shadows as much anymore, there’s often still the need to hide half your cards out of safety and fear of non-acceptance.

What many LGBTQ people wish for is a future where they don’t have to come out or feel pressured to come out. And while it used to be a very personal and community-based process for Banks in the ’60s, the context was grounded in the fact that it was incredibly unsafe to be out in public when she was a teenager.

Now, Generation Z LGBTQ Americans speak about feeling pressured to come out to be seen as valid, both in and outside of LGBTQ spaces.

Sabrina Vicente, a 22-year-old pansexual nonbinary femme, tells GO that when they came out in 2006, they felt pressured to tell their family who responded by saying their bisexuality was a phase. “LGBTQ people have existed since the beginning of time and shouldn’t have to come out, or feel pressured to come out, unless they want to,” Vicente says.

Vicente believes that moving beyond the narrative of coming out is going to take “advocating for LGBTQ friendly sex education everywhere and having a more constant representation of marginalized LGBTQ folks.” In my opinion, moving beyond the need to come out as LGBTQ is not actually up to queer and trans people. We need non-LGBTQ people to work harder at decentering heteronormativity. Undoing the need to come out will take not assuming that everyone is straight and cisgender until they tell you otherwise. It’s going to take not gendering people based on their outward expression and actually checking in with pronouns for everyone you meet. It’s going to take using gender-neutral words like partner or significant other in conversations, rather than simply assuming the new coworker sitting next to you has a husband and not a wife.

Sam Manzella, a 22-year-old bisexual queer woman, reminded GO that coming out—as it stands in our culture right now—isn’t a one-and-done process. “It’s an ongoing thing: we come out in new social settings, work environments, friend groups, sometimes explicitly or in more subtle ways.” Coming out isn’t always a big announcement, sometimes it’s showing up to work expressing your gender in a way that feels affirming, instead of dressing in traditional “women’s” or “men’s” clothing that is expected of you. Or it could be casually saying “my girlfriend” in conversation with a new friend out at the bar one night. We come out in so many different ways and often these processes are not for or about ourselves—but our straight counterparts.

While Sam doesn’t know if the need to come out will ever dissipate while living in a world where cis-heteronormativity is the implicit norm, she did want LGBTQ youth to remember this: “Labels are amazing and carry great power. But it’s OK to question your sexuality or gender identity or to not have the right word for what you’re experiencing. It’s OK to not have a grandiose ‘coming out’ moment. It’s also OK to change how you identify over time. Ultimately, we need to accept that our journeys are our journeys to define, and the journeys of other LGBTQ people are in their hands.”

Pippa Lilias, who is 16-years-old and identifies as pansexual, hopes to live to see a day when queer people don’t have to come out and “the common decency of not expecting [an] explanation of sexual expression [is] extended to queer people.” After transitioning from public school to homeschooling, Pippa found it easier to embrace her sexuality without the presence of bullying from her peers. While campaigns like It Gets Better have an impact, the reality is that many LGBTQ youth in America are still dealing with isolation, bullying, familial abuse, and struggling with acceptance.

Dayna Troisi, fellow managing editor at GO, feels that coming out is empowering and necessary. “I feel like a grandma when I say this, but there’s this sense of entitlement in the younger generations saying they shouldn’t have to come out. Well, sure, you don’t have to. But visibility saves lives. You should be proud and thankful for the battles our queer elders fought just so we could come out. And yes, you are different. Be proud of that. You have to come out because most people are straight. That’s a reality. People assume straightness and cis gender-ness because most people are. That isn’t a bad thing. C0ming out, to me, celebrates our beautiful difference. Plus it gets you laid!”

Everyone I spoke to for this piece had a different coming out experience in completely different generations, but one thing remains true: They all strongly believe in the importance of coming out and wish that it could be a process that is simply done for the empowerment of the person taking pride in their identity.

When I asked Johnson if she had any last thoughts to share with me on coming out, she said she wanted all LGBTQ people who are feeling isolated and alone right now to know that there are folks who love you and know exactly what you’re going through. There’s an old LGBTQ colloquial phrase—people used to ask, “Are you family?” Johnson said it’s code for Are you one of us? Are you LGBTQ? Because at the end of the day, LGBTQ people are connected. We’re family.