Strippers Get Real About Lap Dances, Queerness, and a Sex Positive Utopia

“Stripping affords us the financial freedom to enhance and invest in our lives.”

The first night I ever stripped, I asked four of my femme friends to come to the club to see me and support me. It was a day shift, and the club was mostly empty. First shifts are usually day shifts, and dancers have to work their way up to the coveted night and weekend spots. This didn’t do anything to ease my nerves.

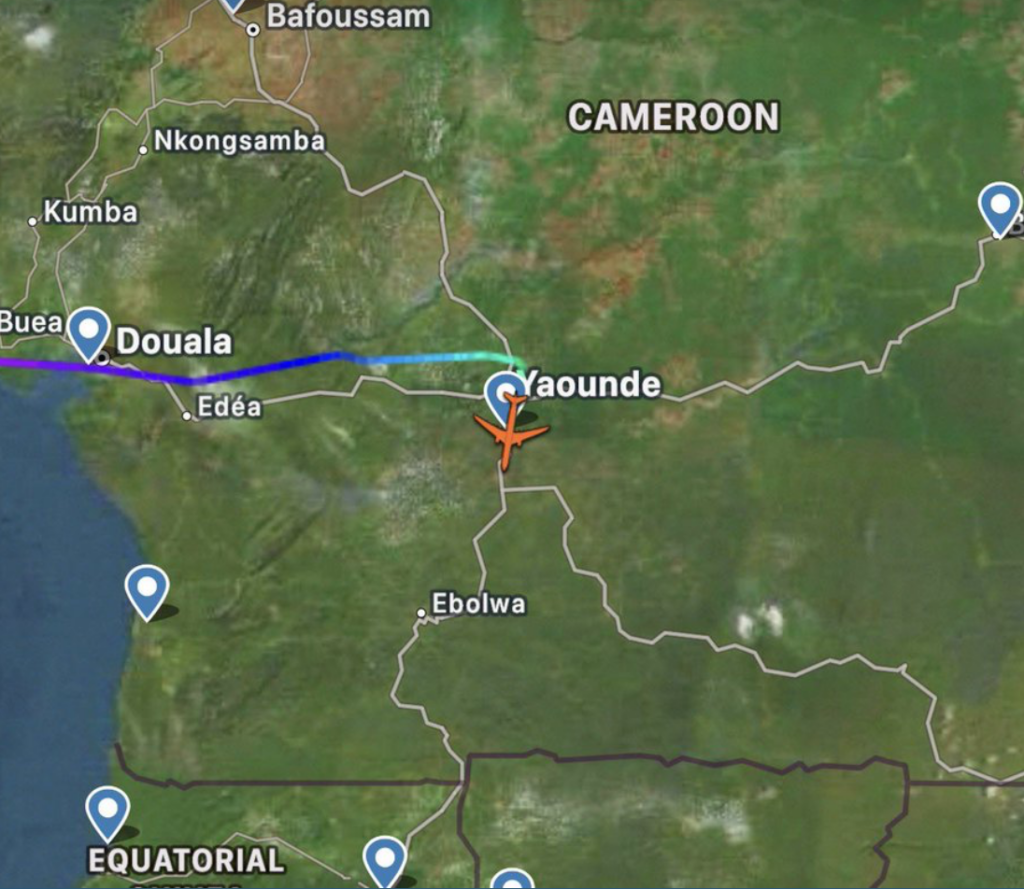

The club was Pumps, a small neighborhood spot in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Long and narrow, awash in purple and blue UV light even in the middle of a hot summer afternoon, walking into the club felt like walking into another dimension. I wondered if all babystrippers felt that way on their first shift. There were motorcycles hanging from the ceiling, with fuzzy bits of cotton from last years’ Halloween spider web decorations stuck to the spokes in the wheels. A sign, mounted above the mirror in the middle of the stage, instructed customers to throw down some cash or “take their broke asses home” in flashing red block text.

Though I don’t work there anymore, Pumps—unlike many other strip clubs—has an excellent reputation among the dancers who work there, many of whom stay loyal to the club over the course of years.

Pumps is also, almost by design, a creative space. The first floor is the club, and the second floor is a recording studio. Nearly all the women I know from Pumps are involved in one or several creative endeavors outside of dancing—from burlesque performers to fashion designers, from fitness instructors to professional pole dance competitors and teachers. And in some cases, Pumps even directly encourages dancers in their creative pursuits. Some of the first women I met there used to practice their doubles routines early in the day shift, if the club was relatively empty, performing feats of stunning athleticism while hardly breaking a sweat. Another dancer swung herself around the pole seemingly effortlessly, a grin sparkling across her face. The bartenders weaved around the bar, which wraps around the stage, and somehow avoided her long legs, as if navigating lithe limbs and 10-inch stilettos zipping two inches from their faces was as simple as navigating a busy subway platform. I was in awe.

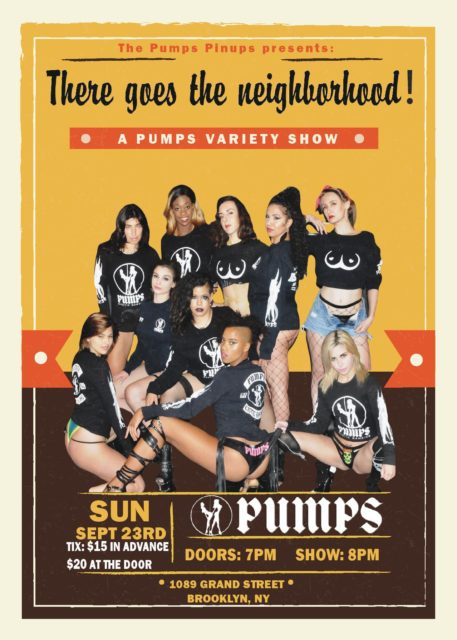

The bar also opens its stage to performances organized by the dancers, hosting a medium that blurs the boundaries between stripping and burlesque. On Sunday, September 23, Pumps will host one such show, with proceeds going to the Sex Workers Giving Circle. I worked with the Giving Circle as a fellow this past summer, and it was an immensely rewarding and inspiring experience. So I’m particularly excited to know that my former coworkers are working in tandem with the SWGC to continue to support sex workers around the country. Bianca Dagga, one of the first dancers I met as a babystripper, is organizing the show. Bianca sat down with me, along with her colleague Louie Loveless, to discuss sex work, artwork, creative expression, and creating the sex worker affirming utopia of our dreams.

GO Mag: I’d love to hear a little bit about your act, or your art more broadly. What inspired your act? What does performance mean to you? And how do you bring your experience as a stripper/sex worker to your art?

Louie Loveless: My act is a re-imagining of the lap dance scene from Tarantino’s Death Proof. It’s my way of engaging with a piece of art that I love, despite the fact that it came from the mind of a problematic man who is too comfortable using graphic depictions of violence against women in his films, seemingly just for shock value. In my version—which also has an added strip tease component—the lap dance is received by another female performer (in drag), and everyone makes it out alive.

Bianca Dagga: I’m actually doing two numbers. My first act is a neo-classic bump and grind burlesque number. It’s a nod to classic 20th-century burlesque, which in addition to satire and extravaganza, was the only form of adult entertainment up until the 1960s when topless go-go clubs took over. My second act portrays the evolution of burlesque into modern-day stripping. It is also a tribute to my Puerto Rican Heritage, set to a 1960s Boogaloo Latin jazz song called “I Like It Like That.” Cardi B sampled that song in her song “I Like It” so I fused both songs. And throughout the act, I’m stripping down from my more classic burlesque costume to a strappy stripper-esque harness, essentially removing the layers of stigma of what is deemed “classy” and what isn’t.

I’ve been performing burlesque for 10 years, and a strip joint stripper for five. Stripping in itself is a beautiful art form that has its roots in burlesque. Essentially, it’s in everything I do. I have learned valuable life skills and self-confidence, among other things, from both performing burlesque and stripping that I utilize every day. The entire show is actually a benefit for Sex Worker Giving Circle at Third Wave Fund. It’s a way for Pumps Bar—a microcosm of the sex worker community—to give back to the sex worker community at large.

GO: What are some things about strippers that people most often get wrong?

LL: Stripping—like all other forms of sex work—is real work. It’s not illegitimate, and it’s not “easy money.” It requires a high degree of physical, mental, and emotional labor that not everyone is capable of putting forth. And regardless of whether an individual is practicing survival work or has simply chosen to strip, they deserve to be treated with respect and compensated appropriately for their labor.

BD: One of the most recurring misconceptions about strippers that I see often is that girls who turn to stripping don’t have much else going for them. That couldn’t be farther from the truth. The vast majority of women I’ve met while dancing at the club (myself included) are creative, dynamic individuals who have multiple streams of income, who are students, artist, activists, mothers, business owners, and more. If anything, stripping affords us the financial freedom to enhance and invest in our lives.

GO: The zine Feral Feminisms wrote in one of their issues that addressed bi-, femme-, and whorephobia, “There’s nothing straight about sex work.” Does your experience reflect this? What does the intersection of queerness and sex work mean to you?

LL: Sex work has a long history as an alternative to traditional employment for many groups, including the queer community. It can serve as a refuge for people who face discrimination in mainstream professions, as well as an outlet for creative self-expression that is difficult to find in conventional workspaces. Of all the environments I’ve worked in, Pumps Bar has the largest and most visible queer community, by far.

BD: Yes, my experience absolutely reflects this. For LGBTQ people, [sex] work has been a means of survival and a way to rise above oppression.

For me, queerness and sex work intersect in the sense that the queer rights movement and sex worker rights movement both fight to achieve body autonomy and liberation. I feel that as a queer woman, I am able to navigate customers swiftly because my queerness acts as a natural boundary. A lot of dancers I know are queer as well. I see stripping as a form of drag performance. It is not always easy to deal with such heteronormativity; in those moments, I channel my high femme energy and turn out a show! At the end of the day, stripping and all sex work is work, and whether you’re queer or not, we do it to survive, to thrive, and to meet our life goals, just like anyone else working in other industries.

GO: What does sex worker inclusive feminism mean to you? In your opinion, what makes a good ally?

LL: Sex worker-inclusive feminism demands that mainstream feminism not sacrifice us for the sake of respectability. Any form of feminism that neglects or excludes marginalized groups to gain popular acceptance really isn’t worth having to begin with. True allies recognize this, and advocate for sex workers when necessary, while also creating space for us to express ourselves and identify our own needs.

BD: Sex worker inclusive feminism is where sex worker exclusionary radical feminist (SWERF) ideology is dismantled. Inclusionary and intersectional feminism is not harmful to the lives and livelihoods of sex workers. A good ally is someone who does not police our bodies, someone who advocates to protect and empower sex workers. They work to de-mystify whorephobia, as well as honor the sexual agency that sex workers require to do their jobs safely and efficiently.

GO: What would your sex work positive utopia look like?

LL: Ideally, I would like to see sex work in all forms recognized as legitimate work, decriminalized, and de-stigmatized. I also believe that all people engaged in sex work should be afforded the same protections and resources traditionally granted to workers in “conventional” industries, including (but not limited to): access to health care, legal protection against discrimination and harassment, and effective means to report and investigate violations of these protections.

BD: My sex work positive utopia is a place where sex workers are not looked down upon, and sex work is widely accepted in society. It is a place where sex workers are afforded legal protection as well as safety within the industry. It is a place where sex workers get paid their asking rates, and it is known that sex workers come in all ethnicities, shapes, gender demographics of people, and not the typical stereotypes that are portrayed.

**

Come support Bianca and Louie and all the incredible Pumps performers at There Goes The Neighborhood on Sunday, September 23rd!

Tickets: $15 in advance, $20 at the door