I was in the middle of reading the trendiest lesbian book of 2020, “In The Dream House” by Carmen Maria Machado, when I came across an *alleged* fact about Eleanor Roosevelt that they definitely did not teach in my U.S. history class. Namely, that she had a long-lasting lesbian affair. Did you know that? I did not.

Machado’s passage is about how archives are never neutral; power and politics determine which stories are kept, and which are omitted or even destroyed. “Sometimes the proof is never committed to the archive,” Machado writes. “Sometimes there is a deliberate act of destruction: consider the more explicit letters between Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickock, burned by Hickock for their lack of discretion. Almost certainly erotic and gay as hell, especially considering what wasn’t burned. (‘I’m getting so hungry to see you.’)”

I immediately put the book down and began investigating Eleanor Roosevelt’s lesbian relationship, and the story was so enthralling that, truth be told, I almost forgot to go back to Machado’s book. (“In The Dream House“ is very good, so that’s saying a lot.)

First, a primer for those who don’t remember the stuff they did teach in U.S. history class. Eleanor Roosevelt was the First Lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945. She was the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, or FDR, who remains one of the most revered presidents in U.S. history. Eleanor Roosevelt, too, made history; she redefined the First Lady role by being far more outspoken and politically active than her predecessors. She did many impressive things in her lifetime, from championing civil rights for African-Americans and Asian-Americans to serving on the UN Commission on Human Rights.

Roosevelt was almost certainly queer. Her marriage to FDR was a matter of politics, not love. She had many close friendships with women who were out lesbians, and she exchanged thousands of steamy letters with close “friend” reporter Lorena Hickock.

Hickock was an accomplished woman in her own right. She was a boundary-breaking reporter at the top of her field covering news, politics, and sports. Nicknamed “Hick” to Roosevelt and all her friends, Hickock was the first woman to have her byline featured on the front page of The New York Times. She was known to be a lesbian.

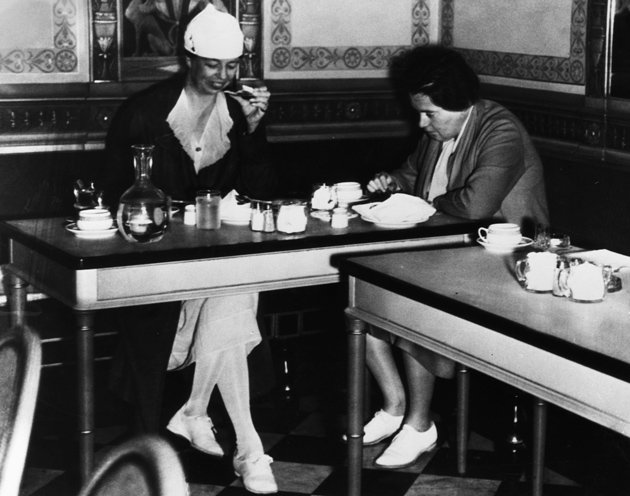

Hickock and Roosevelt first crossed paths when Hickock was assigned to interview the future First Lady in 1932 during FDR’s first presidential campaign. By the following year, they were spending almost every day together. They became so close that Hickock could no longer cover the Roosevelts objectively; instead, she got a job as a researcher for FDR’s New Deal initiative. She moved into the White House — in a bedroom conjoining Eleanor Roosevelt’s. Ahem.

By this time, the two were already very intertwined. But because of their jobs, they spent a lot of time apart, too. In the age before FaceTime and cute selfies, they were forced to write daily letters of longing to each other, and truly — what could be gayer?

Roosevelt and Hickock’s letters became available to the public in 1978 as per Hickock’s will. Spanning their entire 30-year relationship, there are over 3,000 letters in total. But as Machado writes, this record isn’t complete; Hickock burned hundreds of the more explicit letters. She told Roosevelt’s daughter, “Your mother wasn’t always so very discreet in her letters to me.”

The surviving letters include passages like:

“I want to put my arms around you, I ache to hold you close.” —Roosevelt to Hickock on March 7, 1933

“I can’t kiss you so I kiss your picture good night & good morning!” —Roosevelt to Hickock on March 9, 1933

“I love many other people & some often can do things for me probably better than you could, but I’ve never enjoyed being with anyone the way I enjoy being with you.” —Roosevelt to Hickock on March 10, 1933

“Most clearly I remember your eyes with a kind of teasing smile in them, and the feeling of that soft spot just northeast of the corner of your mouth against my lips.” —Hickock to Roosevelt on December 5, 1933

And of course, the excerpt that Machado highlighted in “In The Dream House:” “I’m getting so hungry to see you.” That was from Roosevelt on November 17, 1933, just before the two reunited to spend Christmas together. (All of these passages are sourced from a collection of the letters called “Empty Without You,” edited by Roger Streitmatter.)

Even after the romantic relationship faded, Hickock and Roosevelt remained close friends and continued to meet and correspond (also very lesbian).

With Hickock basically cohabitating with Roosevelt in the White House for several years, it seems impossible that FDR didn’t know about their relationship, not to mention the general public. FDR must have been cool with the arrangement, possibly because he also had his own affairs; their marriage was more strategic than romantic.

Amy Bloom, author of the fiction book “White Houses,” told Australia’s ABC News that there are likely two reasons that Roosevelt’s lesbian affair never became much of a headline.

“I think it is one of those peculiar times that homophobia was actually a great friend to them,” Bloom said. “Because it would have been shocking to say that the first lady was a lesbian, because it was at that time shocking to say the word lesbian, to even bring it up would be to put yourself in the category of the perverse.”

Moreover, the media was accustomed to being discreet when it came to the Roosevelts’ personal lives. They’d already been ignoring FDR’s own infidelity, partly because he had a disability and used a wheelchair. The press wasn’t exactly interested in skewering the man.

Sadly, we’ll never really know just how much gay sex has taken place in the White House. WHO KNEW.

Today, Eleanor Roosevelt’s lesbian affair is far from a secret. In a post-LGBTQ+-civil-rights era, you’d think that a former First Lady’s queerness would be common knowledge by this point. But it’s not. Instead, many historians continue to deny that the pair were ever romantically or sexually involved, insisting instead that they were just “really close friends.” (Yeah, okay.) Any queer woman who even glances at those letters will instantly recognize one of her own. But all too many queer women don’t even know about this part of history in the first place.

“It’s something that is hiding in plain sight,” says playwright-actress Terry Baum, who plays Hickock in the one-woman play “Hick: A Love Story” (via Haaretz). Baum attributes this to the fact that homophobia is, sadly, still alive and well in the 21st century.

And that’s a shame, really. Queer visibility is important. But also, if more people knew about this aspect of Roosevelt’s life, they’d see that she “had such guts to do this thing, to follow her passion, and to live a life that was not just politically forceful and exciting, but also a personal life that really gave her a lot of happiness and pleasure – that she just went for it,” Baum says.

Like most real-life love stories, this one didn’t have a simple happy ending. After Hickock and Roosevelt transitioned from romance to friendship, life went on: Hickock started seeing another woman, and later, FDR passed away. Hickock suffered from health problems, and she often struggled financially. Eventually, she moved into Roosevelt’s cottage in Val-Kill, New York.

The two women continued to support each other until Roosevelt’s death in 1962. Hickock passed in 1968. In her will, Hickock left her and Roosevelt’s letters to the U.S. National Archive to be released 10 years after her death.

Now that LGBTQ+ history is being mandated in some public schools, one can only hope that Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickock’s love story will finally reach its rightful place as an important part of queer U.S. history.

What Do You Think?