Some wonderful artists go unnoticed during their lifetime or even for many years after their death. Other painters find initial success but then fall out of fashion. Later generations may come to realize their true worth (most famously in the case of Vincent Van Gogh).

For the Danish artist, Gerda Wegener, her works were largely forgotten until the release of the 2015 film, “The Danish Girl.” Wegener was rediscovered not in her own right, but rather as the partner of her spouse, Einar Wegener, who undertook the painful journey to transition as a transgender woman in a time of societal hostility and disbelief.

There is much more to consider about Gerda Wegener, including the nature of her relationship with Einar. In the movie, an unruffled straight marriage is upended out of nowhere when Wegener’s ballerina model fails to show up for a session, and Wegener asks her husband to don female attire for the first time and pose for her. From that point on, Einar began to dress in women’s attire, letting buried feelings emerge to the surface.

Gerda is portrayed in the film as the shocked and anguished wife who becomes the champion of Einar’s transition to Lili Elbe. In several scenes, Gerda’s attempts to have sex with her partner are rebuffed. However, Elbe’s own diaries reveal that the relationship with Wegener was strongly loving but platonic. Wegener didn’t annul their marriage, which most heterosexual wives would have done in the circumstances.

It’s possible that Wegener sensed and accepted Elbe’s transition for her own reasons, which weren’t explored in the movie. In times when homosexuality was illegal, marriage became a cover that protected a couple’s sexual truth from the world. I would speculate, as others have, that was the case with the Wegener marriage. Elbe’s sensational autobiography, “Man into Woman” published in 1933, tells only one side of a more complex – and for me, more interesting – tale.

“The Danish Girl” characterizes Wegener’s many erotic paintings and drawings of women as obsessive representations of Elbe. To support that notion, Wegener is depicted as an unsuccessful artist until she focused on Elbe as her model, and her later success in the art world is totally dependent on these “Lili paintings.” But is this quite accurate?

Wegener deserves to be seen properly as a very talented artist with a queer persona that extends far beyond her relationship with Elbe. Let’s consider her life story and oeuvres.

Marriage and Early Career in Denmark

Born Gerda Marie Fredrikke, Wegener was raised in a conservative Lutheran family in a Danish village and was the only sibling to survive into adulthood. From a young age, she showed artistic talent and moved to Copenhagen as a teenager to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Her first portrait of an elegant, beautiful woman was sold by a prominent art dealer while she was still an art student.

Gerda met Einar Wegener at art school, and they married in 1904 when she was eighteen. In that same year, the fateful session transpired: Gerda’s model failed to show, and she painted Einar’s legs covered by women’s hosiery.

The couple quickly became part of the bohemian art scene in the Danish capital. After graduating from the Academy in 1908, Gerda Wegener’s art career was launched after she won a drawing contest organized by the Politiken newspaper. In Denmark, she became known as an ad illustrator, newspaper cartoonist, and portrait painter in a Renaissance manner.

Wegener was developing into a promising avant-garde artist. Her paintings (many of which used Elbe as the model) were groundbreaking explorations of female eroticism. In images where Elbe appears nude, Wegener has given her the body she dreamed of. Wegener’s women weren’t as a male artist would portray them, as the object of his desire. Rather these were women as subjects, displaying female sensuality and sexual desire freely for themselves. However, these bold, edgy portraits and illustrations caused quite a stir in conservative Denmark.

Paris Years, Wegener’s Mature Style and Artistic Success

Wegener and Elbe moved to Paris in 1912 and remained there for decades, where they outwardly lived as two women in an avant-garde art community. Paris was truly unique in its embrace of gay, queer, and polyamorous radicals, writers, and artists. The French capital was also the epicenter of the leading art movements of the day. It was in Paris that Wegener really found her unique style, an audience for her work, and acceptance for Elbe. She supported Elbe as her art career thrived.

Wegener merged Art Nouveau and Art Deco into a portraiture style that featured languid, sensuous women with rosebud lips, heavy mascara, short-bobbed hair (the “flapper” of the 1920’s), sometimes partially nude or completely nude. Wegener’s erotic drawings and paintings during this period reveal much about her private life and sexuality. There’s even an element of camp and drag at play; sometimes Wegener uses costumes as a cover for queerness – certainly some of the “Lili portraits” are such.

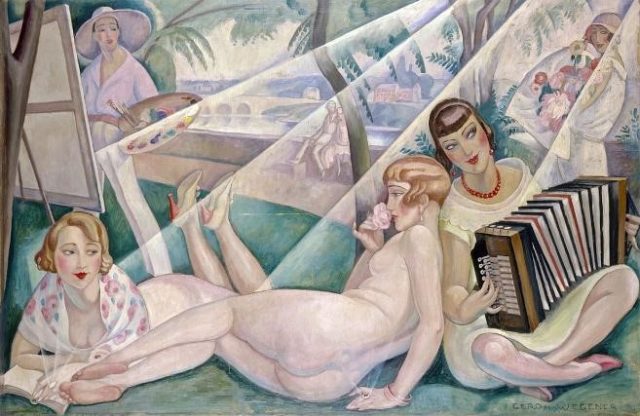

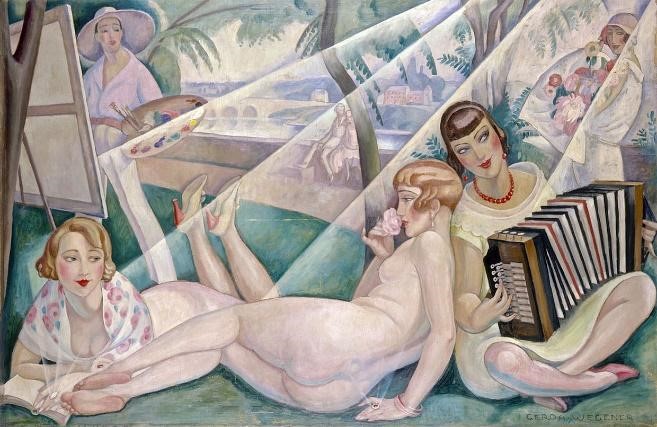

Wegener painted a number of portraits of multiple women like “A Summer’s Day,” a work from 1927, in which the painter (standing in the background with her artist’s palette) stares at her three female models; two of them are nude. There’s a rather flirty vibe to this work, as the nude woman’s toes coyly brush against the other woman’s hand.

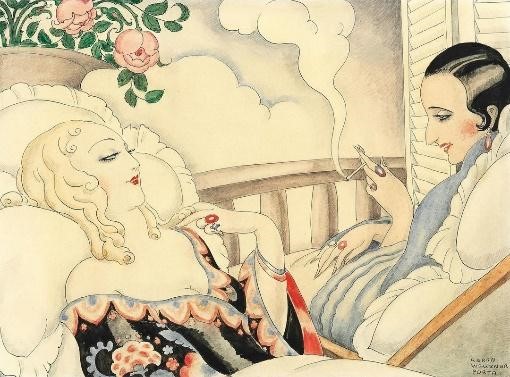

This understated erotic tone is evident in her other paintings of women. Consider the cool, knowing glances between the women in a later work, entitled “Two Women on a Balcony.” It hints at more than friendship between the two: the knowing, languorous glances exchanged and the revealing dress of the blond woman. Everything is suggested, but the suggestion appears repeatedly in Wegener’s oeuvre.

Having a “type” that viewers would instantly recognize was a feature of the leading Paris portrait artists. Take Amadeo Modigliani; no matter who was the model, the “type” was the same: long-faced, arched neck, almond-eyed, tiny-mouthed. Although more sensuous, tender and not experimental in style, Wegener’s works can be compared to other artists of the period who depicted sexually liberated women, such as Tamara de Lempicka.

It wasn’t surprising that Wegener became a hit in the Parisian fashion industry which required images of beautiful women in chic attire. She worked as an illustrator for Vogue, La Vie Parisienne, and other magazines. As an established artist in Paris, Wegener became known for her lavish illustrations (mostly for women’s products such as powders and stockings). Women in Wegener’s fashion paintings consort with cats, recline, and read letters but they are perfectly aware that they are being looked at, and counter the viewer’s gaze with erotically charged ones of their own.

Wegener won a prestigious competition at the 1925 World Fair in Paris, and was a good friend with the celebrated Danish ballerina Ulla Poulsen (1905–2001), who was frequently depicted in her paintings. Poulsen was the missing model that day when Elbe’s journey of gender identity began. In this painting, Poulsen is dancing to a ballet based on the music of Frederic Chopin, likely performed at the Palais Garnier in Paris. Poulsen’s sultry expression and her décolletage transport this work to the realm of the provocative.

Wegener’s Erotic Drawings

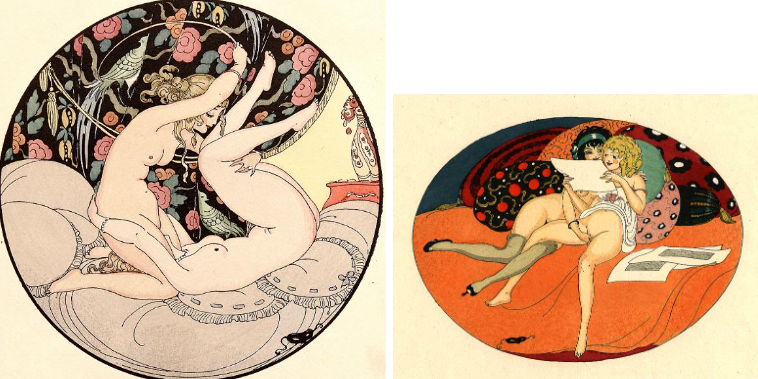

Wegener’s erotic art in the Paris years featured the same self-possessed women she paraded in her fashion illustrations, but in a state of undress or consorting with each other in more than just conversation. One glance at Wegener’s erotic art featuring sex between females shows you that she was very familiar with lesbianism – the happiness, wit and charm of her relaxed drawings suggest that she herself had sex with women. They reveal the queer story that was missing in the Hollywood movie.

Lost and Found

The 1930’s ended in tragedy for both Wegener and Elbe.

Elbe had one of the first gender reassignment surgeries in 1930, which caused quite a scandal in the newspapers. She wanted to have her sex and name legally changed, but to do so, the marriage with Wegener had to be annulled. Wegener readily agreed as she knew that Elbe eventually wanted to marry a Parisian art dealer named Claude Dejeune. However, Elbe did not survive the last surgical procedure in 1931.

After Elbe died, Wegener was heartbroken and looked for a safe harbor. She remarried an Italian officer, aviator and diplomat, Major Fernando Porta, and moved to Morocco where she continued to paint, signing herself Gerda Wegener Porta. However, the marriage was short-lived. She divorced him in 1936 and moved back to Paris, before returning to Denmark in 1938.

By the late 1930s, artistic taste had changed to pure, clean forms – the exact opposite of Art Deco. Wegener fell out of fashion and since her work wasn’t selling, she was forced to support herself in Copenhagen by hawking hand-painted, cheap postcards. The year of the Nazi invasion of Denmark (1940), Wegener died. Only a tiny obituary appeared in the local paper.

Fast forward to 2015 and the release of “The Danish Girl” amidst a wave of transgender activism, visibility, and new found respect. A modern art museum in Copenhagen included 200 of Wegener’s works in an exhibition honoring the 100th anniversary of Danish women’s suffrage. More international exhibits of her work have followed.

Wegener is now appreciated as an innovator and an important contributor to Modernism. She used various mediums to stand up for marginalized identities, queer desire, and a different female gaze which makes her work socio-politically charged. Her work is both revolutionary and feminist; and her sister descendants include women of style, talent and sass – like Lady Gaga, the fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, and the photographer Nan Goldin.

Wegener once wrote, “When painting someone’s portrait, I try to find my subjects’ most beautiful, intimate qualities. That a certain portion of my own personality is added, cannot be avoided, since one has a personality! Can you be an artist without one?”

What Do You Think?