I have a confession to make: before starting this column, I had only seen about 2 classic lesbian films. I know, I’m a bad queer. When I admitted this to my fellow GO coworkers, they were appalled. Two of them quickly listed off at least 10 films I needed to watch right away. I rapidly wrote down the titles (for research, obviously).

I want to take you all along with me in my quest to review all of the lesbian classics through my Millennial queer lens. Last time, I reviewed the half way decent film “The Kids Are All Right.”

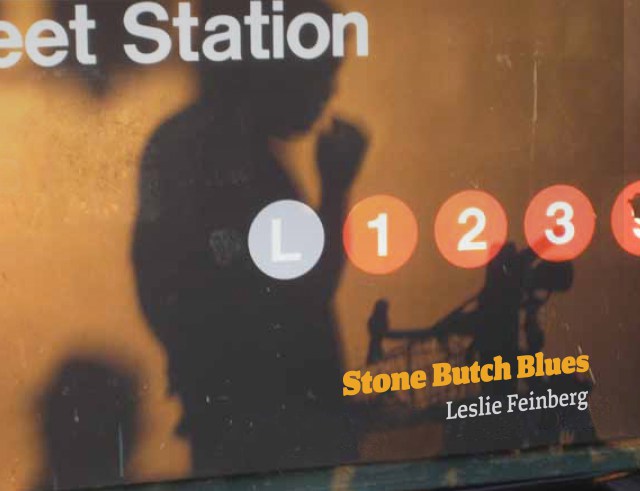

This week, I decided to read “Stone Butch Blues.”

If you’ve been following this series, then you know how exasperated I’ve become with watching lesbian films that revolve around straight, cis white men. So this week, I decided to switch it up and go for a book instead. I’ve had more experience in reading queer literature than watching films but haven’t touched some of the classics. And “Stone Butch Blues” is just that, one of the ultimate classics of queer literature written by activist Leslie Feinberg in 1993.

As I boarded my flight from New York to Palm Springs for the epic Dinah Shore Weekend, I decided to crack open this book that has long been on my reading list. The plane was lifting off the tarmac and tears were streaming down my face within the first three paragraphs. Feinberg starts off the book with the most beautiful love letter written by Jess Goldberg, a young butch lesbian, addressed to an ex femme lover. “After you moved that way, you had more than my heart. You made me ache and you liked that. So did I,” Feinberg wrote on page 2 through Jess’ perspective.

“Stone Butch Blues” has been on my radar since long before I came out as queer. It’s a book that I’ve almost opened so many times, but ultimately put down for another read. I think my aversion to reading “Stone Butch Blues” was out of fear that I wouldn’t relate. As a queer femme, I felt like it wasn’t a book for me and so I put off reading it. This is not to say that we can’t enjoy and love content that narrates an experience different from our own, we absolutely can and that’s half the fun of delving into fiction.

For me, picking up this book was more nuanced than that.

As a baby queer, I knew that the queer folx I was most attracted to were more masculine presenting. And that terrified me. My mom had long asked me, “If you’re going to date someone masculine why not just date men?” Uhhh, not the point, mom. I definitely internalized this thought and veered away from dating masculine queer folx for a while. While my desires encompass more than masculine presentation, I felt as though it was a romantic experience I was intentionally avoiding. Instead of allowing myself to explore my attractions freely.

I struggled with my attraction to swaggy lesbians, dapper daddies and queer people who f*ck with gender presentation. I feared that femme/masc relationship dynamics would mirror the toxic straight relationships I had in the past. I feared that all masculinity was toxic. But it’s not. And reading “Stone Butch Blues” this year was an affirmation of that fact for myself.

“But I couldn’t change the way I was. It felt like driving toward the edge of a cliff and seeing what’s coming but not being able to brake,” writes Feinberg from Jess’ perspective of coming out as a young butch (page 54).

This book, through all of its imperfections and poetic grapplings, invites the reader along for a journey in Jess’ process of navigating masculinity in a world that is built on the toxicity of misogyny and patriarchy. Feinberg shows that the imagination and creativity of queer butches and masculine folx can open up a whole new world to define what masculinity can be when it’s not tied to these virulent systems.

“‘What would our words sound like?’ I looked up at the sky. ‘Like thunder, maybe.’

Frankie pressed her lips against my hair. ‘Yeah, like thunder. And yearning.’

I smiled and kissed the hard muscle of her biceps. ‘Yearning,” I replied softly. ‘What a beautiful word to hear a butch say out loud.'”

Page 301

The friendships between butches in “Stone Butch Blues” are by far some of the most dynamic representations of masculine queerness. Feinberg writes butch-for-butch romantic relationships and the main character, Jess’, own struggle with accepting her friends in those loving relationships. The above conversation is between Jess and her older butch friend, Frankie, when they both recognize how closed off they were in their younger years. She explores how butches so often don’t have the language to express their own truths and vulnerabilities.

Describing masculinity as yearning thunder shows that masculine expression can be divine — that it has the potential to be intimate and expressive and tender. The dichotomy of butch being closed off and femme being tenderly emotional is one that needs to be done away with. And while this book was written in the 90s, not much has changed. There may be less butch/femme identity politics as queerness has evolved, but these ideals are still very much upheld in our community.

However, the characters I most related to and found my home in were the femmes. “The moon is femme, child—high-in-the-sky femme—and don’t you forget it,” Peaches, a trans femme, tells Jess as she admits her own struggles with understanding the femmes in her life on page 142. Femmes are often deemed “too much,” “crazy,” or “high maintenance” all of which are pulled from living in a misogynistic society. And I so relate to femmes being described as the moon. We carry lunar reflective and magnetic energy. We are the tide that pulls people in. We are the reflection that the full, bright moon gives us during a dark night.

Following the narration of a butch queer finding love with and for her femme lovers in “Stone Butch Blues” gave me hope. It gives me hope that my masculine leaning partners will find understanding of my femmeness in a more nuanced way than simply labeling me as “crazy” or “too extra” when I’m expressing my vulnerability. This book allowed me to envision all the ways in which relationship dynamics can evolve, shift and exist in the world of queer identity. I fell in love with my own queerness while reading “Stone Butch Blues,” because I was allowed to use my imagination in understanding that my love doesn’t have to follow a script.

Feinberg’s writing on femmes was like reading affirmation after affirmation. Her love for femmes was so powerful and it overwhelmed Jess throughout the book. The femme characters gave Jess space for her light to begin to shine through all the toughness of her butch exterior.

My favorite passage of the entire book came when Jess’ femme lover, Theresa, was sticking up for her fellow femme sex worker friend, Justine, when she was being accosted by the police.

“Theresa slipped off her high heels. ‘Take your hands off her,’ Theresa told the cop. Her voice was low and calm. ‘Leave her alone.’ Theresa walked slowly toward the cop with the high heels at her sides. I held my breath. Georgetta took off both her stilettos and held one in each hand. She walked over to Theresa. They exchanged a look I couldn’t see and stood side by side.

The cop put his hand on his gun butt. Somehow we all knew instinctively that none of the butches should move.”

Page 139

That is femme solidarity. That is femme understanding. That is intrinsic femme communication, with the glance of an eye. Jess also mentions how the butches knew not to intervene — because they knew the femmes had each other’s backs in a way they couldn’t understand. The nuance in this exchange is so palpable it jumps off the page. After that exchange when Theresa and Georgetta forced the police to back off their friend, Jess admitted that she was scared for Theresa. And Theresa responded by asking Jess if she ever gets scared, to which Jess says “I’m scared all the time.” It’s then and only then that Jess realizes she doesn’t show her emotions to her lover.

The ways in which Theresa pushed Jess to find love for her body and sexuality is reflective of queer relationships I have been in before. I’ve been the femme to gently coax the soft honey out of the core of my masculine lover — and reading these words gave me space to understand how radical that love is. I felt a deep knowing in that moment that queer relationships are inherently radical because our existence is resistance. Regardless of femme/butch, butch/butch, femme/femme dynamics — our love breathes fire to our passions and brings out tenderness and reflects back the same power as the sun and the moon.

“As the world beat the stuffing out of us [butches], they [femmes] tried in every way to protect and nurture our tenderness. My capacity for tenderness was what they’d seen.”

Page 32

Young queer people have little representation for what queer love looks like — yes, there are LGBTQ characters on television and movies now today and we have LGBTQ celebrities like Lena Waithe to look to. But when it comes to love, we aren’t shown how to navigate the messiness. I didn’t have my high school years to be messy in my crushes like my straight friends did. I didn’t know what I was doing when I first ventured into the queer dating world — let alone digesting the ways in which identity can impact how our love evolves.

“Stone Butch Blues” is a beautiful book that shows our messiness. Our imperfections. Our flaws. And that through all of that, we are still deserving of love. It shows the power of platonic intimacy through Jess’ relationship with her neighbor in New York City, Ruth. Feinberg revolutionized the ways in which we understand gender identity and genderqeerness through her writing.

Sometimes I become dismayed by all the community in-fighting or the pure exhaustion of just being queer in a world that wasn’t built for us. Feinberg’s words helped me find my way back to letting love into my world. Her words opened up my mind to all of the possibilities for collective liberation and radical love that truly do exist. Feinberg gave me hope that when we navigate through the forest of our past, we can better pave a path forward that has enough space for all queer people to walk side by side.

As I was finishing the last chapter of “Stone Butch Blues” I was on a plane back from Palm Springs to New York City. It was an empty flight and I had a row of seats to myself. As I curled up by the window watching the fiery red sunrise pique over the crest of the Earth, slow hot tears streamed down my face. They fell to my lap as I read Jess’ speech about experiencing sexual assault as a young dyke to a crowd of queer and trans people on Christopher Street. Jess spoke about how she doesn’t have the answers, “But couldn’t we get together and try to figure it out? Couldn’t the we be bigger?” For much of the book, Jess was alone in her battles. “Stone Butch Blues” is a call to action for queer and trans people everywhere to really, truly see and love one another.

“I’m sorry it’s had to be this hard. But if I hadn’t walked this path, who would I be?”

Page 330

As my flight landed, I closed “Stone Butch Blues” and set an affirmation into the morning sky. To all my queer and trans siblings: I see you and I love you.

What Do You Think?