On one of the last days of 2016, Amy Hunter packed her bags for a flight from Michigan to Arizona with her spouse, to visit the in-laws and ring in the New Year.

She packed a few skirts, some light scarves, a blazer and a long, flowing sweater — nothing she would need at home this time of year. Except for the extra colostomy bags. She couldn’t leave home without them.

In fact, Hunter can’t travel far by plane or even by car without them. The 56-year-old transgender woman underwent gender confirmation surgery 8 years ago, and then spent two more agonizing years trying to fix something that had unexpectedly, horribly, gone wrong.

The surgery “didn’t make me a woman,” Hunter told GO in a Facebook chat. “It was, for me, a necessary step toward removing the incongruities inherent to my gender.”

But that step forever changed her life, in ways she did not imagine.

Surgery is a risky but increasingly popular option to counter gender dysphoria, the feeling that one’s gender assigned at birth doesn’t correspond with the gender identity of that individual. Across America, doctors, hospitals and clinics that perform these transgender surgeries report a boom in demand, according to NBC News. It’s not clear if it’s because more trans people are coming out — the Williams Institute reported 1.4 million American adults now identity as trans — or if they are deciding to pursue surgery before President-elect Donald Trump and the Republican-led Congress make good on threats to scrap the Affordable Care Act.

Of course, not every trans person seeks or qualifies for surgery, often because of personal or financial reasons, their health, lack of insurance coverage, or out of fear of losing a job or their family’s support.

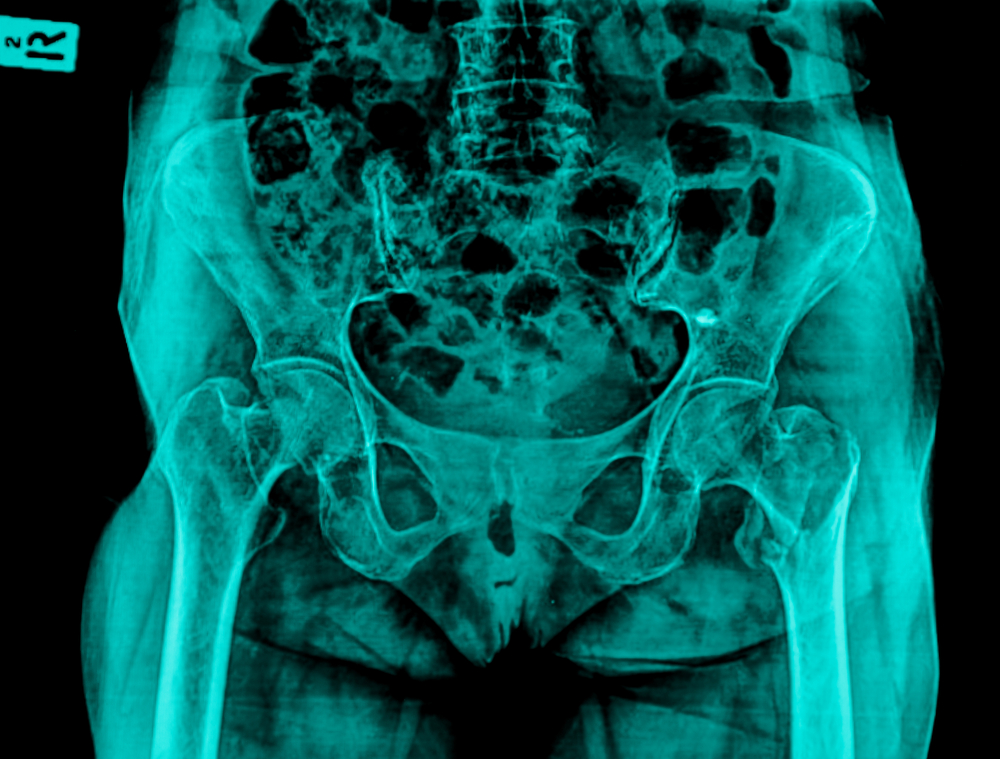

Those who do pursue transgender-related procedures have a range of options, beginning with hormone replacement therapy for both trans men and women. Then there is facial feminization, tracheal shaves, and breast augmentation for trans women, and double mastectomies for trans men. The surgeries that have been indelicately called “sex change operations” are the most complex procedures; a more common name is sex reassignment surgery, or SRS, and a more popular name within the trans community is gender confirmation surgery, or GCS. One more variation is Gender Affirmation Surgery. And since 2014, the U.S. Government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have covered many, but not all, of these transgender-related procedures.

“Generally speaking, it is possible to obtain insurance coverage for gender-confirming surgeries in patients who meet WPATH guidelines for surgical transition,” said Dr. Jess Ting, Surgical Director and Assistant Professor of Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. WPATH is an acronym for the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. “Coverage varies from state to state.”

And while doctors say the vast majority of these transgender surgeries have successful outcomes, the risk is real, and historically, a taboo subject. But that’s changing as the surgeries themselves become more common.

“The demand for surgical transition has been growing over the last several decades,” Ting said. He couldn’t provide hard numbers, and internet searches typically churn out outdated data.

For example, statistics cited in the Surgery Encylopedia are more than a dozen years out of date, indicating that at the turn of the century, between 100 and 500 gender confirmation surgeries were performed a year in the U.S. The entry reported the worldwide number was two to five times larger, with many choosing to have their surgeries in Thailand. Since many of these operations are performed privately, the actual current number is difficult to estimate.

The U.S. Transgender Survey for 2015 by the National Center for Transgender Equality found 25 percent of the more than 27-thousand respondents reported undergoing some form of transition-related surgery, which comes to more than 6,750 operations. Also, 55 percent of respondents who hoped their health insurance would pay for transition-related surgery in the past year say they were denied coverage.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the transgender health program at Oregon Health & Science University had 180 transgender patients on a waiting list last summer, and Boston Medical Center’s Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery had a waiting list with 200 transgender women awaiting vaginoplasty. That is the name of the irreversible operation in which a surgeon transforms parts of a penis and scrotum into a vagina, clitoris and labia. It is not, as so crudely put by the uninformed, the same as “cutting off your dick.” The male urethra is shortened to serve as a female urethra. The reverse is true for female to male patients. And in both cases, surgeons preserve nerve endings to maintain sensation.

At least, they try to preserve those nerve endings. Hannah Simpson, 32, was not so lucky. She lost all sensation and gained something that left her feeling that intimacy was impossible. The New York City writer and transgender advocate lives without a functioning clitoris.

“When I wake up in the morning and take off my pajamas to take a shower, I see this extra flap of tissue that my surgeon left and refused to address. It constantly reminds me this is not yet finished this is not a functional aesthetic representation of the female anatomy,” Simpson told GO in a phone interview.

“It reminds me it’s not done. It makes being flirtatious harder. It makes socializing harder, and just going out harder. Even waking up feels harder. I have to work through that every single day.”

“Complications are a possibility in any surgery, no matter how simple the surgery and GCS is most certainly not simple,” said Dr. Marci Bowers, an accomplished gender confirmation surgeon in San Francisco, who herself is trans. She spoke to GO via email.

“These surgeries include a wide variety of procedures with individual complication rates which correlate with the particular surgery in question and with the surgeon involved. Rates can vary from rare to as much as 30 percent in urethral lengthening procedures,” she wrote. “Fortunately, with time, most incisional complications resolve themselves without intervention beyond local wound care. Unfortunately, genital surgery places great pressure on artistry with complexity of these procedures confounding all but the most precise of surgeons.”

Ting agreed, and put in a plug for the new program at his Manhattan hospital. “Gender reassignment surgery is a complex, multi-step procedure which requires extensive training and expertise,” he said. “This is why, at the Mount Sinai Health System, we have created a multi-specialty center for transgender surgery where patients can receive the highest quality surgical care in a culturally-sensitive, high-volume, tertiary care center.”

Culturally insensitive folks, including far too many health care professionals, tend to ask transgender people, “have you had ‘the surgery?’” That question is frowned upon because being trans is “not about what’s between your legs, but what’s between your ears,” as Chaz Bono famously said.

Last month, Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta hosted a panel that brought together medical students and transgender advocates from the Human Rights Campaign, to help the students better understand trans people’s lives and health needs.

But even within the transgender community, the subject of surgical complications is a topic that has too often been discussed only in hushed tones. Even today, it is typically limited to private social media groups and online chats, which attract large numbers.

“In the trans community, there is a very active online community where there is an open exchange of information on where to have surgery, what the complications are, and who the practitioners are,” Ting said. “Discussions of postop care and complications are common in these online venues.”

Of the three surgeons who agreed to speak to GO, not one will proceed with the operation unless a patient agrees to sign a form that they are aware that complications are possible. “Outcomes —including potential complications — are part of every discussion with prospective patients,” Ting said.

“Complications do occur, however. Obtaining long-term outcomes data, including complications, is one of our goals. There is no current registry process for transgender surgery and outcomes, and it is our hope to establish a multi-institutional longitudinal outcomes registry. Similar to cardiac and transplant programs, a future scenario where publicly or voluntarily reported outcomes data are available to prospective patients would be desirable.”

If a database is created, it will come too late for Hunter, who is the transgender advocacy consultant for the American Civil Liberties Union in Michigan. She’s known she was not male since the age of four.

Instead of the vagina she had always longed for, Hunter has what she called a “fibrous lump between my legs and a colostomy bag.” Everything she read online and in an information packet, everything her surgeon told her, led her to believe the chances of complications were at best remote.

“Almost as an afterthought, she said we needed to go over ‘this stuff.’ We got to that last, not worth mentioning but still possible, worst-case scenario thing,” Hunter said. “Of course, it needed to be brought up but in almost four hundred surgeries ‘it had only happened just once, so we don’t worry about it.’ I didn’t.”

That’s a decision that has haunted Hunter, Simpson, and two trans men who also shared their stories of surgical complications.

“Why did I do this?”

Ryan is a transgender man who said he’s always felt like he’s a guy, and rejected the label lesbian when he was younger. He spoke with GO by phone, and although he asked we not use his real name or identify his home state, he’s made no secret of his struggle on social media, like Hunter and others who’ve encountered complications after his “bottom surgery.” That is a phrase many in the transgender community use to refer to the specific operation that female to male trans people undergo, a phalloplasty, in which tissue from an arm is used to create a phallus that allows a trans man to urinate in the same way he would if he had been born that way.

Ryan said although he had done his homework, he still had doubts prior to being operated on by a world-famous surgeon in Illinois. While Hunter chose to not name her surgeon, Ryan decided others might benefit from knowing about his experience with that surgeon, who declined to be interviewed or offer a comment on the record. He is medical director at a Chicago clinic for transgender men and women.

“I wondered, ‘Am I doing the right thing?’” Ryan said. “There’s this huge potential for complications.” And so there were.

“I started having urinary complications almost immediately, less than a week,” said Ryan, who developed a stricture, which is an abnormal narrowing of the urethra, the tube that carries urine out of the body from the bladder.

There were also problems of a far more basic nature during his recovery.

“My disappointment is that I don’t feel like the communication from my surgeon was there at all,” Ryan said. “I felt abandoned. There was no help. Thank goodness for this one amazing nurse practitioner. She was a godsend who was always available, because [the surgeon] certainly was not.”

“I found him in a private, secret group I was in,” on Facebook, said Ryan. “I really liked his work.”

Ryan had turned to the surgeon in spring of 2016 only after “a horrible, horrible experience” with the office staff of a male surgeon in San Francisco, a doctor he decided to not name. “They blew me off, it took six months to get back to me, they wouldn’t answer the phone, and they wouldn’t return phone calls. I even emailed the doctor several times,” said Ryan, who heard from friends there had been a major snafu in which several scheduled surgeries were canceled en masse in the midst of the doctor’s move to the Midwest. Ryan finally gave up after nine months and made a consultation appointment with the Chicago surgeon.

“I felt really good about my consultation in April,” Ryan said. “There were far fewer people who had negative experiences with him; in fact, people I talked to had really good experiences. I looked at his results and they were hands down the best I had seen.”

Following his radial forearm flap phalloplasty on May 31, the doctor required he lay prone for six days, forced to maintain nothing more upright than a 30-degree angle.

“[The surgeon] would come in, he’d take one quick look,” Ryan said of the days following his operation. “He’d be in the room for less than two minutes at a time, he’d go, “Hmm. Looks good,” and he’d walk out. “And I had pus and infection concerns for almost the whole first month after surgery,” which was the first of two he spent in the hospital. But he said his surgeon seemed nonplussed.

“He even examined Gary in the shower,” said Ryan.

Gary talked with GO by phone. He teamed up with Ryan for this odyssey and underwent the same procedure with that same surgeon. Like Ryan, he is trans, and also asked that we use a pseudonym for legal reasons. From late May until mid-July, he was by Ryan’s side, except for that one morning in the shower.

“Seeing that Gary wasn’t in his bed, [the surgeon] went and examined him in the shower,” Ryan explained. Gary picked up the story: “He walked in on me, in the shower.” He said the doctor pulled back the shower curtain, and asked him, “Can I take a peek?”

“I was like, ‘Um… I’m showering, but okay,’” Gary recalled with laughter. “The R.N. standing behind him just gave me a look of horror when he asked that.”

“We have this joke now that when you pull back the shower curtain we expect [the surgeon] to be standing there,” Ryan said, reminiscing about the classic film, Psycho. “It was the talk of the floor for days.”

Gary had the same complaint about their doctor as Ryan: “We were just so frustrated by our aftercare, specifically the lack of communication. For example, I emailed [the surgeon], asking, ‘there seems to be an area underneath my scrotum that is opening up, is that normal?’”

Anyone reading that kind of message would no doubt be alarmed at that development, but Gary said the doctor’s response was disappointing: “Put gauze on it.”

“I was like, ‘Are you kidding me with this?” Gary said. “I never questioned whether I should have had the surgery but I thought to myself, ‘this is so hard. Why did I do this?’ When I questioned whether it was worth it, each time I would think to myself, ‘you know what? It’s going to be worth it. It’s just hard right now. It’s a hard road. You’ll get to the point of being okay.’ I admit, I expected it to be 100 percent happiness, when I had visions of what recovery would be. It turned out to be more of a mixed bag.”

“I got really depressed and shut down. I gave up on myself.”

Like Gary and Ryan, Hunter spent her recovery seeking new surgeons, and she underwent several reconstruction surgeries to repair a rectovaginal fistula that had resulted from a slight tear in her colon. A fistula is a hole between the vagina and the rectum that in women who are assigned female at birth is typically a complication of childbirth, and allows stool to flow through that hole into the vagina.

Hunter said a surgical tool called a retractor caused her tear, during what she described as “an otherwise flawless procedure” by a leading surgeon in this field whom she chose to not name here. But as it happens, those attempts to fix what went wrong backfired horribly, leaving her not with an approximation of what every woman has, but with something that left very much to be desired.

“Unfortunately, all of the efforts at repair failed,” she said. “I got really depressed and shut down. I gave up on myself.”

“Those two years of multiple procedures after GCS were rough. That many surgeries, the general anesthesia and the pain meds take an extraordinary toll on your body and emotional health. One surgery made the problem worse having severed some critical muscle tissue. I have a permanent colostomy and no vaginal canal. But, and it’s a big but, I have been able to use my experience to help others, including some physicians, understanding the need for integrated post-op care. I was fairly depressed for awhile and it was really difficult to get off the opioids, but eventually, life became pretty routine again. I was unable to do much physical work for those two plus years, and I left my previous profession as a lighting designer and went into advocacy and politics. Ironically, I guess, my difficulties nudged me to take seriously what I already knew was a moral imperative, and live it. Living with a colostomy becomes routine but takes some adjusting. I learned to give myself more time in the morning and to let, ahem, things move, before I get in the car for a long commute or on an airplane.”

Speaking of planes, Hunter said because of her colostomy bag, “I ALWAYS get pulled out by security for an “anomaly” and tested for explosive residue by TSA.

She learned to not see herself as lacking anything: “It wasn’t so much having something, as clearing away that which blocked me from my authenticity as a woman.”

“I am a woman, and that is unequivocal now,” declared Simpson, who shared a similar fate to Hunter’s, but has all but given up hope after a frustrating series of surgeries that made things worse, not better.

“A woman who does not have functional female anatomy.”

“One surgeon finally washed his hands of me, saying, ‘Well, you did this to yourself.’”

Simpson had her bottom surgery in Philadelphia and has chosen to not name her surgeon. As is typical, the success of the surgery — or lack thereof — was not apparent at first. Recalling her recovery in July 2014, she said the sensation of the cuffs that surrounded her calf muscles, constantly pulsating to circulate her blood flow, “that was more painful than the recovery from the surgery itself.”

But a far different pain was soon evident. Before sending her home, the packing was removed and she was instructed on vaginal self-care, such as dilation and abstinence from sex for three months.

“I looked at it and saw some marked asymmetry, even from the first day. One side was very swollen and firm, and the other side was a lot softer; still swollen but there was a difference in texture,” said Simpson, who at the time was in her second year of medical school, studying to be a doctor.

“I was told, ‘The tissues could be swollen at different levels, it’s hard to predict. Give it time to heal. This particular surgeon wanted to keep everything open as opposed to compression garments,” Simpson said. And when she reported the asymmetry had increased, she said the surgeon scolded her for wearing Depends post-op, claiming the tightness may have exacerbated the swelling. “I said I don’t think that’s the case because a number of other surgeons use compression dressing in their protocols, and I didn’t have that pair of Depends on for very long — we’re talking ten minutes — and I even ripped them to make them wider, didn’t wear them all the way up and replaced them with a bigger pair the next day.”

“I’m watching it heal and I’m watching it necrose,” — which means the tissue on one side of her vulva was dying — ”and I know what is happening, because I’m a medical student and it becomes clear within the first few weeks that I’m going to need a revision, a labiaplasty. I was told it’s just going to fill in on its own, and no it wasn’t. I had follow-ups, first a week, then a month, then three months. And each time the asymmetry is persisting and it looks like shit. And I’m also having issues with the vaginal canal itself as well as the vulva. One surgeon, then another, and yet another look at me, and they won’t do anything. One finally washes his hands of me, telling me, ‘You did this to yourself.’”

While Simpson’s and Hunter’s cases are said to be rare exceptions, both women expressed no regrets in terms of choosing to have their surgeries, even in spite of the complications.

Simpson — who has no need for a colostomy bag — did find a use for them: as a prop in a successful Twitter campaign to fight North Carolina’s House Bill 2. She attracted support from transgender author Jennifer Finney Boylan, activist Brynn Tannehill, supermodel Geena Rocero and more, with the tagline: “Legislating peeing is legislating being!”

As part of her activism tour around the world in 2016, Simpson also visited Ryan and Gary in Chicago last summer, at the beginning of their seemingly endless recovery.

“I feel like I lost three and a half months of my life.”

Gary agreed that he wasn’t sorry he had the operation, but there was an enormous amount of frustration, and he endured it for more than three months.

Imaging from a tiny camera that was inserted into his bladder in July revealed Gary had a urinary fistula. “While it was explained to me these are common, it’s been so, so hard to deal with these catheters.”

Not one. Two.

“If I were to go into a locker room now,” he said in August 2016,” there wouldn’t be any concern aesthetically, but someone would surely wonder, ‘Oh, why does that guy have two catheters?’”

One was a penile catheter, known also as a Foley, which was inserted into his penis; the second or pubic catheter was inserted near Gary’s stomach and acted as a fail-safe in case of complications once the Foley was removed.

“It’s been frustrating that here I am, three months later and I still can’t pee standing up. I was supposed to get the catheters pulled a month ago but they say I’m not healed enough,” Gary said, exasperated, last August. “I usually don’t cry, but I’ve broken down three times. It’s a mixture of frustration anger, annoyance. It’s a pain in the ass. It’s not painful per se, it’s just annoying. I feel like I lost three months of my life”

By mid-September, that problem was resolved, and both Gary and Ryan said they are glad to have made a joint decision to ditch that doctor, leave Chicago and find another surgeon.

“We felt like our complications were not being addressed,” said Gary, who had the fistula; Ryan had the stricture that he felt wasn’t adequately treated. “We have different body anatomy and yet we have the same complications. We feel, honestly, that [our surgeon] didn’t give us his best, ‘A’ game. I’ve never had a health issue all my life and to be in a hospital 31 days, that’s saying something.”

Ryan and Gary are members of the same group on Facebook where trans men can share their concerns, both pre- and post-op. Gary found it invaluable.

“By discussing with other trans men I realized, I’m not alone, and there are lots of guys with urinary complications,” Gary said. “And even though this recovery has been really challenging, it is ‘normal.’”

The surgeon they chose for the “fix” was Dr. Dmitriy Nikolavsky in Syracuse, N.Y., who is fast developing a reputation in the transgender community.

“I found a niche, for fixes,” Nikolavsky told GO in a phone interview. He said he doesn’t do gender affirmation surgeries, at least not right now. “The original surgeries are much more difficult,” said Nikolavsky, who said he always consults the surgeons before he begins work on one of their patients. “I compliment them. They are doing the impossible.”

Nikolavsky said he was stunned to find a terrible shortage of research to guide him as he learned his technique, which he said was not more difficult than the same kinds of surgeries on men assigned male at birth, and women assigned female at birth. He did concede, “nobody knows the ‘correct’ procedure, given that there are only three papers in the world addressing this topic, two from the 1990s and a more recent paper from Belgium.

“But no matter what you do, in some complications, you have very little success,” Nikolavsky said.

While acknowledging many of his transgender patients express shock and disbelief at their complications, Nikolavsky said most of the cases he encounters are, “in the grand scheme of things, tiny setbacks, minor problems after a complex surgery,” that he has developed a skill in resolving, including in the case of both Ryan and Gary, who drove eleven hours from Chicago to Syracuse last summer to find their “fixer.” Both men are living authentically now, tubes out, back at work, and they pee standing up, just like any other guys.

Their friend Simpson hasn’t stood up to urinate for years, but one of her complications is that the flow of her urine skews forward instead of downward, yet another problem that sets her apart from cisgender (not transgender) women. Still, she said, peeing was the least of her concerns.

Three months after her surgery, she asked her surgeon what the plan was for having sex, a major reason she chose to have the operation in the first place. She is the oldest of four children, a snarky Jew from New Jersey who boasts that she used the money she had socked away from her bar mitzvah — the Jewish ritual in which a boy becomes a man — to become the woman she always felt she was. “I want to be able to use my vagina, and I don’t feel like I’m going to be able to have sex, which is typically three months.”

“A pear is not an apple.”

The surgeon’s response stunned her: “’If you were in a relationship that would be one thing. You just want to have sex for the sake of having sex.’ And all I could think was, ‘Excuse me, mommy?’ She should have no say in how I’m using this vagina.”

Simpson wanted a second opinion on getting a revision, but most surgeons she consulted at this point told her the same thing: let it heal, see if it improves on its own. It didn’t.

Ultimately, a surgeon in California did perform a revision in 2015, which Simpson said left her looking butchered, and feeling damaged beyond the point at which she worries if she ever experienced sensation during intercourse.

“A number of things are wrong: I do not have a clitoris, which makes it really hard to achieve stimulation leading to an orgasm. I do not have symmetric and complete labia on either side of my vagina,” Simpson said. “And I have tremendous scarring in the vaginal canal that needs to be addressed, shaved down, in order to have comfortable penetration. I also have excess urethral tissue that was just left out. It’s an angry inch, just sticking out from the top of my vulva. And I lost the nerve endings that were attached to the tip of my penis, and those nerves are still leading toward where they were, but something needs to be attached to them to restore sensitivity. You can string power lines to a house but if you knock out all the light switches, what’s the point?”

Simpson is hoping she might find help as more doctors do more procedures to repair complications, and has appealed to Dr. Nikolavsky among others around the country and the world for help. “I cannot be the only one person this has happened to, let alone the last person.” She believes there might be a solution in the breakthrough work being done on male soldiers who survive bombings and require genital reconstruction. Simpson also actively supports the cause of women who have been tortured through genital mutilation, something with which she closely identifies. “I’m cognizant of the significant difference between my surgery and the experience of women worldwide who are subjected to this horror, but I can see in the aftermath a parallel, and I can’t help but identify with their plight.”

Friends, especially those who are pre-op transgender women, have tried to convince Simpson to move on, to concede that she’s lucky to at least have had access to surgery, even if it did not end well. Those appeals do not help, Simpson said.

“’It has to be better than not having a penis,’ they’ll say. And I’ll say, ‘No, actually there’s something worse than having a penis, and that’s a nonfunctional, not aesthetically accurate vagina.’”

Or they will tell her that somewhere out there is someone who will love her for who she is, not what she looks like below the belt.

“They’ll say, ‘you’ll find a partner who understands.’ And my response is, the standard for surgery is, I did it for me, I didn’t do it for anyone else. It shouldn’t be about my partner when I’m uncomfortable with the result I have. And then they’ll say, ‘vaginas come in all shapes and sizes.’ But when you’re outside the natural range, that doesn’t work. Apples come in all shapes and sizes. A pear is not an apple.”

Some of the toughest conversations have been with her very supportive mother, who’s told Simpson, “I support you for being a woman. What more can I do?”

“And I say, ‘nothing,’ and that alienates them because they want to do something,” she said. “But the hardest part is the physicians that you look to, some try to be honest, they’re primary care doctors, they say, ‘We don’t have a clue about this, you’re on your own. I felt like I already died. I already died. Now I was just in limbo in between when my life as a spirit ended and when my physicality ended, and that I wasn’t exactly pushing to die but I wasn’t living either. Thank God my family was supporting me.”

“Right now I’m taking it one day at a time,” she continued. “I’m doing lots of things to distract myself, like staffing trips to Israel, writing, traveling, because I know if I go back to something like medical school I will fall back into depression. I am traumatized every time I wake up, get naked, take a shower, use the bathroom. Just looking at it, it’s a trauma. And it’s a continuous one that I carry around with me. It is connected to me. It is me. I cannot remove it from myself and I cannot remove myself from it. And that is devastating.”

Simpson said her only regret is her choice of surgeons and can accept that. “What I can’t accept is being shrugged off. I am a woman who has a right to a functional anatomy. Any woman, cisgender or transgender, would feel that way. What are we going to do about that?”

She’s still waiting for that question to be answered.

What Do You Think?