Audre Lorde’s Work Is Still An Urgent Call To Action

Reading Lorde’s work feels like church.

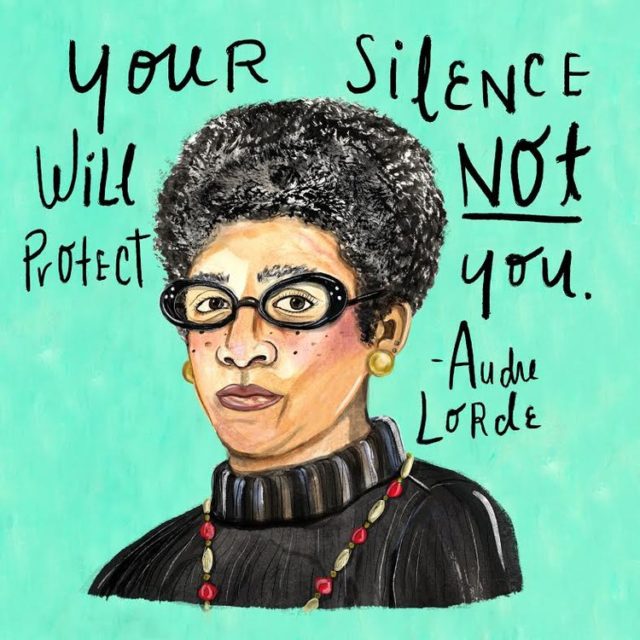

There are a few books in my life that have completely changed my perception of the world. Audre Lorde’s “Sister Outsider” is by far the most important book on that list. It’s a collection of essays and speeches and reading them felt akin to seeing all the internal turmoil about my existence in my body finally legitimized. “Sister Outsider” was originally published in 1984 but it nevertheless feels as urgent and relevant as ever. “Your silence will not protect you,” words from Lorde’s 1977 essay The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action are etched into my brain and remind me not to keep quiet about my suffering.

Last year, in the spirit of not passively watching the world change, I went to the Women’s March in Los Angeles with two other women of color. It was insanely crowded, almost a million people were stuffed into the streets downtown. I don’t remember hearing any of the speakers but the line up was star-studded. I remember biker gangs and funny signs and dogs and so many children. The music was coming from everywhere, all of it at once. It didn’t feel like a protest, it felt like a street festival.

I by no means identify myself as an activist. I had never been to a protest before. In fact, I always struggle to understand where my social and political responsibilities lie as a queer African non-citizen in this country, with little political capital. But after spending the summer watching Black activists get tear gassed and arrested in Baton Rouge and Ferguson, that day after Trump was elected didn’t feel like a protest.

This year I decided not to go, both purposefully and accidentally. If I learned anything over the past year, it’s that activism can look a lot of different ways. There are no definitive rules and guidelines for how to properly fight against oppressive structures, and political change is unhurried. But there is an underlying defect in the narrative surrounding the Women’s March, a persistent diseased brand of feminism that’s exclusionary and stubborn. A feminism that is cisnormative. A feminism that conflates misogyny and racism as if they can’t be experienced simultaneously.

The Women’s March was originally called the Million Women’s March after the event organized in 1997, but was criticized for essentially co-opting the work that Black women activists did. And although the board of women brought on to handle the event were primarily women of color, the general pro-Hillary, 53% of us voted for Trump but still want to be the face of the resistance narrative, is very much present. Protesting has become a stage for performative activism and who has the funniest sign contests. After all those people showed up all over the country last year after Trump’s election, roughly 63% of white women still voted for racist pedophile Roy Moore in Alabama.

It’s hard as a women of color, as someone still trying to understand what my activism should look like, to be convinced to march in solidarity with women who only know this glamorized branded version of protest when I’ve grown up in world that’s inundated me with images of people that look like me being shot and arrested for doing the same thing. It’s hard for me to justify listening to actors still willing to work with Woody Allen talk to a sea of ironic pink pussy hats. It’s like instead of finally listening to activists of color who’ve been fighting systematic oppression for the breadth of American history, Trump’s election gave white liberals the brilliant idea of commercializing protest, a la Pepsi ad.

I didn’t go to the march this year for a myriad of reasons. Most importantly it because it’s a reminder of what people show up for. When our communities are attacked, when trans people are beaten to death, when Black lesbians are murdered, when Black men are shot by the police, 750,000 people don’t show up for us. We have to cough up a lung screaming just so we don’t die in silence. So it’s disheartening when we realize that when you chant that women’s rights are human rights, both the words women come with the caveats white and cis.

One of the most fundamental flaws in this kind of feminism is the conflation of sex and gender, hence the never-ending uterus paraphernalia present at the marches. Womanhood is not biologically denoted because gender is performative. In fact, claiming that transgender women aren’t really women because they haven’t had the same struggles as cis women use patriarchal oppression as the basis of the very definition of womanhood. If your goal is to move away from the patriarchal structures that work to keep women subjugated, how do you justify basing the criteria of what makes a woman solely on that subjugation? I personally am not in the business of trying to contextualize my existence based on my oppressor’s perception of who I should be. The issue of hierarchy that exists within the binary is a vital reminder that everyone enjoys a certain level of privilege. And for some reason when some feminists are making arguments about the supposed erasure that the inclusion of transgender women promulgates, they dismiss this.

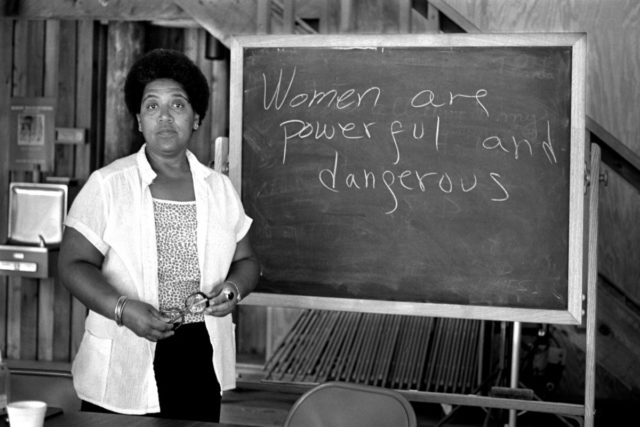

In 1979, Lorde wrote a letter to feminist philosopher Mary Daly in response to her book Gyn/ecology. The letter, which appeared in “Sister Outsider,” criticized Daly’s exclusion of Black women in her meta-ethical observations. “To imply…that all women suffer the same oppression simply because we are women is to lose sight of many of the varied tools of the patriarchy. It is to ignore those tools are used by women without awareness against each other.”

Having to explain that inclusivity and erasure are not mutually exclusive doesn’t feel like a radical statement in the realm of progressive thought, but it seemingly is in many feminist enclaves.

The manifestation of the kind of rigid feminism that refuses to be self-aware is dangerous. The kind of feminism that sees victimization as a virtue and hence concludes that having the right body to be violated is the standard by which we measure womanhood. We are not women because our bodies are violated. We are not women because of how we’ve suffered. Lorde extensively wrote about how sad it was that we rob ourselves of each other for the sake of willful misunderstanding and lack of compassion.

Especially because queer and Black history have been systematically destroyed, it’s comforting to have a voice that lives on, immortal through every passing generational chaos, a reminder that we are surviving even though we were never meant to. Reading Lorde’s work feels like church. Every word of her work, whether it’s poetry or prose, feels like redemption and validation. The kind we need in especially trying times to remind ourselves that the world also belongs to us.