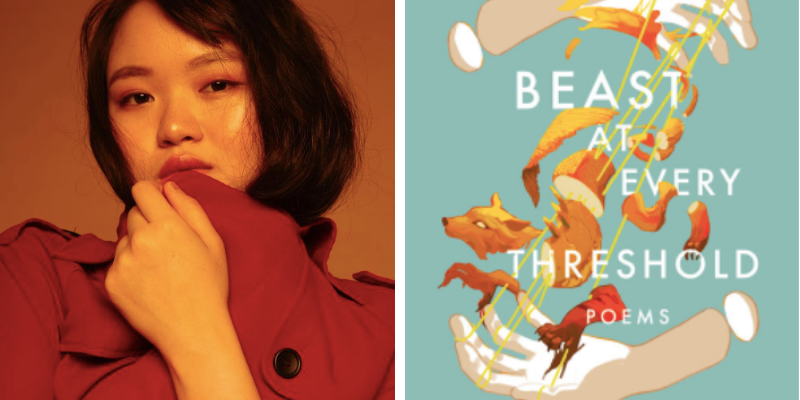

The Miraculous Mingles With The Horrifying In Natalie Wee’s ‘Beast At Every Threshold’

Her Mouth A Door, After Which / There Is Another Door

A few weeks ago, I kept a secret from a very timid cat. We were going to the vet. I placed his kennel in our small bathroom while he slept and arranged a thick towel by the tub to wrap him in and protect myself from his claws. I woke him up, gently lifted him, and attempted to comfort him with a litany of embarrassing whispers. When I closed the door behind us, every muscle of his lean body tensed. He kicked out my arms with the force of an MMA fighter. In that confined space, he thrashed, he squirmed, he fought. But once he realized he was trapped, he went still. He curled tightly into himself and pressed his body to the back of the carrier. This is how animals, including–I suppose–myself, react to containment.

These competing instincts are tied up in the title of Natalie Wee’s second book, Beast at Every Threshold. Her poems investigate what it means to thrash, to tear, to rip about, to beat the fiber from the husks, while also exploring how we hold our bodies, our relationships, and our histories together. The characters in these poems include fixtures of contemporary queer pop-culture like Rina Sawayama or Korra and Asami–the will-they-or-won’t-they couple of Nickelodeon’s Avatar the Last Airbender sequel–as well as monsters, whales, dogs, and a former classmate who opened “a doorway beneath the desk because she wanted escape & thought to summon one with desolate, shaking fingers.” They are characters who are trapped by the conditions of pop-stardom, race, history, or body. Each is looking for a door or a mouth, which these poems infer might be the same thing.

These are poems deeply interested in gateways. They explore the architecture of our bodies. How our mouths are thresholds for desires and languages, how politics and history enable and prevent intimacy, and how every memory is a story we tell ourselves.

“She was told everything / is allegory, aphid-heavy foliage & lusty flowers, / fat koels naming themselves / to cicada applause,” Wee writes in “Instructions for a Transmutation Circle,” conjuring a mother who realizes the world is rebuilding itself around her daughter. “God gathers her tools” she writes. “Her mouth a door, after which / there is another door.” In Wee’s syntax pronouns are shared and bodies fuse one into another. While this creates intricate webs of relationships, it is also exactly how mythmaking works. We bind ourselves to stories of the past–verifiable and impossible–create monsters who lash out for our anxieties, and stars for our desire and joy. “To write,” Wee says, “is to cradle myth / & memory both & emerge with the fact / of your flesh.”

As anybody whose body deviates from white cissexual and nondisabled standards knows, to be different is often to be portrayed as monstrous. Early in the book a girl encounters this transformation:

We were shored clean of fathers,

throated harsh American accents

& muzzled breathing, only to be offered

a name half-pronounced. Haunting,

the border agent called me, instead of Huan Ting.

A single exhale dislocating phantom from girl. At the next

checkpoint, fluorescent menaces Mama’s dark hair.

The long vowel of incoming headlights.

In these situations, Wee pinpoints the mouth as the wound, the blade, and the source of healing. “So she knifed a belly made for easier spoils, sewed her tongue backwards. / Until she could not drink but held clay behind teeth / for daughters to build stairways out of.”

All across this collection, miraculous and horrifying transformations occur. Incredible violence unfolds, landscapes and architectures are reconstructed, and even the poems branch. Sometimes the stanzas of her poems are diamonded across the page, inviting the reader to choose which facet to follow. Reading the poem in a different direction transforms the image seen through it. Other times Wee writes in the form of a crossword puzzle or, in one particularly fun and harrowing poem, the branched choices of a monster dating simulator.

One possible exchange goes like this:

What keeps the body from other bodies?

You want to know if you’re safe

All I have are these hands

What else will save me?

The other possibility:

What keeps the body from other bodies?

You want to know if you’re safe.

What will save me then?

Loneliness.

Whose loneliness?

And how long have you been lonely?

In between these options and other visions one consistent trend becomes clear: the bodies of living things are, like all celestial bodies, subject to gravity. From loneliness the speakers of these poems reach out. Wee imagines, in one poem the letters “Asami writes to Korra for Three Years.” In her living room, Wee reports how her roommate’s dog is “fucking something she imagines loves her,” and, in the hyper-lyrical habits of a person in love, the speaker of one poem praises her ex and sings “O tender thorn, O most beautiful / splinter/ O sweet bruise / O my fleeting joy upon this earth / praise your careless shimmy, as you flower pink mornings / via cast-iron pan & stove. Praise a tongue so wondrous / you pronounced my longing / a day kind enough to sleep through.”

Wee knows that every time we open our mouths, we open one of the sliding-doors to our future. It’s a cliché for a reason, because it’s true. The rooms we create without language are not always the ones we want to walk into and yet we do. The characters in Wee’s rooms inhabit fantastic and realistic spaces. They reconfigure their voices and their bodies to fit. “I knew you first as the shape of some bird / & then the warble that quickens air into spring….It’s magic, how / another diasporic darling makes / where are you from sound like sisterhood / instead of a reminder I’m not really from here,” she writes. But perhaps the most preternatural ability of these poems is to reject the old joke this life chose me and instead “Choose a hell of your own making over the hell that unmakes you. Flower / a garden of rage & eat & eat & eat.” It’s like Franny Choi once said, “if they used it against you, it is yours to make sing.”