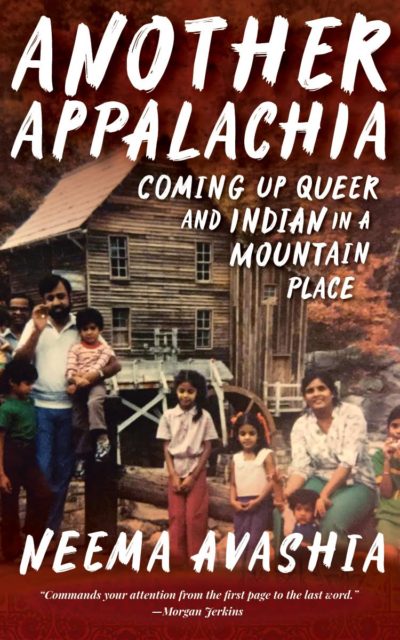

“Chaat masala goes on everything,” writes Neema Avashia in her new memoir collection, “Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian In a Mountain Place.” The tip comes from one of her essays, which delves into the different ways her Indian-born parents incorporated the tastes of their homeland into the not-always-as-flavorful cuisine of West Virginia’s Kanawha Valley, where they had immigrated in the 1970s.

The fusion is an apt symbol for Avashia herself: both Indian and Appalachian, a mixing of identities that many Americans probably don’t associate with the eastern mountain region. But the lucrative job market of West Virginia in the 1970s and 1980s, and the need for skilled scientists and engineers, was a boon for families like Avashia’s.

In “Another Appalachia,” Avashia explores her intersecting identities as a queer, first-generation child of Indian immigrants growing up in the mostly straight and white world of the Kanawha Valley. But this isn’t a memoir of racial struggle and trauma; while she does recall the painful epithets and racialized harassment that one would expect from a racially homogenous place, the West Virginia of Avashia’s world is filled with good, kind people who care for one another, who treat neighbors as family.

Although Avashia lives in Boston now, where she teaches in the city’s school district, her home state isn’t far away. She speaks to GO via Zoom from the designated West Virginia room in the home she shares with her New York-born wife, which appropriately, contains items from West Virginia – including the wedding quilt her mother made, which she proudly displays for the camera.

West Virginia is still very much on her mind, in all its complicated glory: from its twisty politics to its economic downturn, its rich mountain environment and complex people, whose diverse narratives, defying stereotypes and expectations, are told in Avashia’s book.

GO Magazine: What made you decide to write this book now?

Neema Avashia: I really do think that the 2016 election was a real turning point for me in the way I thought about the place where I grew up. And that was happening for a couple of reasons. One is that people who I had grown up with and who I had had really loving relationships with as a young person were using social media to post just really painful content, anti-immigrant content, anti-black and brown content, anti-queer content. And it was this real moment of dissonance for me where I was like, ‘How can it be that you know me, you saw me, I was at your house, I ate at your table?’ In many cases, they were people I considered almost like family. But that wasn’t stopping them from posting this stuff, and from espousing it. And it just kind of gave me pause, because it made me realize, like, oh, I don’t know if they totally saw me. So part of it was somehow, people weren’t seeing us. And I felt like I wanted to be seen. And I wanted my family’s experience to be seen. And I wanted the community that I grew up in to really be seen and to let people have a visual of what this experience was, of being immigrants, being brown, in West Virginia.

GO: You wrote that your family had such different reactions to your work. In India, they pretty much disowned you for writing about family matters which they believed should be kept in the family. And even your own parents, you’re very guarded with what you share with them. Are you going to share this book with them?

NA: I had a really good conversation with my sister last night, she just finished it. I think [our parents] are going to read it. I made the decision that I was going to wait for them to read it until it was out. And that’s complicated. I don’t think that’s a decision that everyone agrees with. But I think that, when you layer gender and sexuality, and race on storytelling, it gets harder and harder and harder to tell your story sometimes, and the amount of space or permission you have to do that can really become smaller, and smaller and smaller. And on some level, I sort of felt like if I had to write this book, and know that someone was going to have to say yes or no to whether it was okay to put in the world, like, I wouldn’t be able to write it.

GO: You’re never going to get that approval of everyone who might appear.

NA: No, I couldn’t have written it. And that’s hard. I recognize that it’s my story, but it’s other people’s stories, too. I just felt like I needed to tell the story. The story was important to more than just me, or more than just my family. I feel like the story is a story that has resonance for a lot of people who live in rural places, who live at intersections and communities that are homogenous.I think there’s just a lot there for people who are trying to navigate identity in contexts where what they see around them doesn’t reflect who they are. And that power feels more — it has a lot of weight. And so I sort of erred on the side of like, I’m going to do my best to write with empathy, and to hold everybody in this with as much love and empathy as I can and to implicate myself 20 times over anything critical that I say about anybody else, but I’m just going to write, and I’m going to accept the consequences afterwards. But I’m not going to stop myself from writing.

GO: You do talk about the examples of racism and xenophobia you encountered as a young brown girl growing up in West Virginia, but so much of the book really does focus on kinder moments with people you’ve formed connections to. What made you decide which memories would become part of this collection?

NA: I think what’s interesting is that the racism and the xenophobia were often one-offs. It’s a horrible thing that happens and it happens in a basketball game, or it’s a horrible thing that happens, and they’re not people I have relationships with, they’re people who don’t know me, right? And then the kindnesses are so often in the context of deep and sustained relationships. And so in a way as a writer, there’s only so much you can mine the racism for. You can talk about what happened, you can talk about the way it impacted you. But exploring in depth, it’s limited what you can do with it. Whereas like a relationship that’s sustained, you can really dig into and spend time thinking about the way that relationship shaped you. And those relationships for me generally were nurturing relationships. I think for my sister, she doesn’t have the same attachment to West Virginia as I do, because I think for her, the negatives really outweighed the positive experiences and the relationships. I was lucky. I feel like I had sustained relationships, mentors, people who are willing to be like, ‘Alright, you might be different from us, but I’m gonna, like, bring you into my circle.’ That mitigated, in some ways, the pain of those, those individual instances of racism.

GO: One of the things that you talked about struggling with was telling people whether or not you’re queer. When did you come out as queer to yourself? And when did you start sharing that information with your family and some of the people in your West Virginia circle?

NA: Yeah, I mean, late. like, I think — wait a minute, I teach eighth and ninth graders and like, so many of them are already like, ‘I’m bi! I’m queer!’

GO: It’s a very different world.

NA: I’m so grateful that they live in this world. But I did not live in that world. I was 30 before I kind of was like, ‘Oh, this whole thing that I thought was my life is not my life.’ And it really was in the context of meeting my partner, that a lot of that became clear. And then very quickly after that, I was like, ‘This is this is real.’

I think that there are a couple of layers. That, one, like I’ve talked about in the book, I didn’t know any queer people growing up in West Virginia. And so not having models of that meant that like, I just didn’t know. I think queerness was the thing that like floated in the aether of like, ‘Oh, I don’t think I’m expressing my gender,’ or ‘I’m not like other people.’ That I was very clear on. But am I not like them because of race? Am I not like them because of gender stuff? What is the ‘not like’ because of? I think it was harder for me to find language for, because I just didn’t have models. And then I think also there was this layer of cultural expectation, which is like, ‘What are Indian women supposed to do? And who are they supposed to be? And how are they supposed to act?’ So I was parsing both the Appalachian parts of that and the Indian parts of that. And I think parsing both of those things just took a really long time.

GO: How does being up north, being in Boston, make you see the place where you grew up?

NA: I think it has given me a much greater appreciation for the culture of Appalachia and the culture of the South, and the way in which relationships are such a priority or have been — again, I think, I think that the 2016 election really did some damage in the south in terms of eroding some really long-held cultural values, and really turning people against each other in ways that are hard. But that said, I think that Appalachia has a lot to teach the rest of the country about what it means to be in relationships with people, and to sustain relationships, and to really let being with other people be the thing that you’re doing. The running joke I have with my partner [who’s from New York City], she goes with me to these rural places and she’s like, ‘What do people do here?’ And I’m like, ‘People are just with each other.’ Like, that is the thing you’re doing. You don’t need to do a thing. Particularly in the pandemic, I thought this was just, like, such a revelation of this. This past year, everyone’s like, ‘I can’t go to a restaurant, I can’t go to the movies, I can’t do this thing.’ And it’s like, ‘Well, you know, we can go sit in someone’s backyard at a fire and just be with them. It’s lovely. So I think that way of being with one another, I feel like it’s such a lesson. And I don’t think I could have learned it if I hadn’t moved somewhere where it’s not the way people are.

GO: I thought that was very sweet in your book, how you would talk about the way people will foster relationships with their neighbors and how that, in India for your parents, they had always imagined that your family were the people you have these close relationships with. But when they came [to West Virginia] it was your neighbors that you formulated these connections to.

NA: I think, also, that sense of appreciation for place is a very Appalachian awareness that I don’t think exists in other places. Every Appalachian person I’ve met, I’ve encountered in any way, there’s this rootedness in place and geography that I feel, like, is different. Being [in Boston] I can see it. I don’t feel people feel connected to the land. That sounds cheesy. I don’t mean it in a cheesy way. But I think when you grow up in the mountains, you’re always really aware of how small you are. I think in a city, that kind of awareness isn’t there.

GO: Would you go back to live in Appalachia?

NA: I’m a teacher, and right now in the West Virginia House of Delegates they are currently talking about passing legislation that would make it illegal for people to teach about issues of race and racism in the public schools. They also are passing legislation that is anti-abortion, and agencies that allow queer people to adopt can’t get money from the state government. The legislative realities of West Virginia make [living in Appalachia] feel like it’s not really possible. While, on some level emotionally, I might really miss it. I might wish that and I see queer people and brown people, Black people living there and fighting and fighting in ways that I’m so inspired by. But it is hard to think about making the decision to leave a state where I have a significant amount of freedom as an educator, as a queer person, as a brown person. There are [in West Virginia] people actively trying to pass laws that erase me. And I, on one level, feel deep pain for and deep solidarity with the people who do live there, who are fighting against that legislation. And I also am like, ‘What does it mean to choose to live in a place that wants to erase you?’

GO: How do you reconcile emotionally the place that you loved with the place that’s legislative least trying to erase people like you?

NA: I really feel like the political landscape in West Virginia, and nationally, I think that people are being sold a narrative that is really dangerous, and that is really wrong. They’re being sold a narrative of division, and they’re being sold a narrative of scapegoating and blaming and saying, ‘Well, these are the people who are responsible for all of our problems. And if we just get rid of these people, or if you just don’t learn this thing in school, or these people just don’t have rights, everything is going to go back to being better.’ I think that’s an agenda. I think it’s a political agenda. And I think that human beings, we want a narrative, we need a narrative to understand what’s happening around us. I think people have been sold a really bad narrative. And I think that that’s also part of writing the book, is to be like, ‘I can offer you another one.’ It’s not the only one. But I feel like I got to offer you another one.

GO: In one of your essays, you talk about how growing up [in the 1980s and 1990s], West Virginia was a deep-blue state politically. What caused this switch from dark blue to ruby red?

NA: The loss of work. When I say there are no jobs, they’re literally not jobs. You can work in Walmart, you can work in a federal prison or you can work in the service industry, but, you know, when I was growing up there were union jobs. There were union jobs in the mines and there were union jobs in the chemical plants and union jobs and union benefits and union pensions. And here was a significant chunk of folks who, with a high school education, could live a middle class life. That’s gone.

GO: Among the last moments in the book, you were writing about how you struggle to decide whether or not you really are ‘West Virginian.’ After having finished this book, and looking back on your past, do you identify as an Appalachian?

NA: I think in some ways, the writing of the book, and then the way that folks in Appalachia have received the book, has almost been like the most confirming of that. If I had to like rank in order –which is a weird thing to do — but if I had a ranking order, how the different communities who are reflected in the book have received the book — and the three are the Appalachian community, queer people, and Indian people — I would say Appalachian people have been the most excited, welcoming, like, wanting to be in conversation, of anyone. So that’s been kind of amazing, because that’s the space where I’ve had the most questions, and it’s the space where people have just been like, ‘You don’t need to have that question.’ So that’s just been really, really lovely.

I just just think there’s a host of Appalachian literature that is amazing, that is putting out these different narratives, but they’re not the narratives that are getting the hype because they don’t confirm stereotypes that people already have about Appalachia. And so I think for people in Appalachia, anytime there’s a story that confirms what they know to be true, instead of what people want to say about them, it’s a really powerful moment. So yeah, I think it is almost easier for me to use that word now than it was when I started to write the book.

“Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian In a Mountain Place” is available from West Virginia University Press, or you can order online at your local booksellers.

What Do You Think?