I met Harvey Milk on Valentine’s Day in 1978 at a well-known night spot called The Elephant Walk in the Castro, the gay district of San Francisco. I was single again, out with my best friend, Steve, to catch the show. The Walk looked like an orange-and-white-striped circus tent, crammed full of exotic night creatures.

After we ordered a second round at the bar, Steve grinned like a Cheshire cat as three guys sat down behind us. I turned around, instantly recognizing one of their faces.

It was Harvey Milk, the first openly gay San Francisco City Supervisor who had become a prominent national leader for gay rights. Steve introduced me. Harvey and I shook hands. He was a lanky Jewish guy with tousled hair, a smile broader than the Bay Bridge, with deep creases framing his cheeks and protruding ears like those my father and I shared. Wit and intelligence exuded from his eyes.

Harvey had one request. “Please get out and vote this November, Emily. We’ll need everyone’s help to stop Anita and the Briggs Initiative.”

John Briggs was a gay-bashing state legislator who sponsored a California ballot initiative that effectively would have barred gay teachers from public schools. Anita Bryant was the TV mouthpiece of Florida orange juice and the founding homophobe of this latest crusade.

I couldn’t tell Harvey that there was no way I could vote. At the time, I was a fugitive with four felonies for burning draft files in 1969, an act of conscience against the Vietnam War and racism. I was never captured, rather I voluntarily surrendered in 1989. Those years are the subject of my memoir, “Failure to Appear; Resistance, Identity, and Loss,” published in March 2020.

“California’s going to come out!” Harvey hoisted his beer bottle over his head. His table companions cheered, as well as every shade of gay at the surrounding tables.

Harvey lifted my spirits. Like so many of us, I was downcast and pessimistic during the Nixon years. Harvey revived resistance, unity, and hope. Somehow, we must defeat the Briggs initiative. It was the first round of carving up our civil rights.

*

San Francisco’s Gay Pride, on the last weekend in June, wasn’t going to be just a naughty, fun affair. The Briggs Initiative loomed on the November ballot. Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk were to lead the parade. The parade theme, “Come out California,” was the perfect double entendre.

I drove up early to the city to meet up with Steve. On Market Street, rainbow flags fluttered from every light standard from Castro Street to the Civic Center.

At last year’s parade, I retreated far from the curb, remembering the fugitive rule: stay clear of political protests, period. But my militant mood had returned after an eight-year slumber. The gay rights struggle was different than the ‘60s peace movement, because it was personal—my rights, my identity. I couldn’t vote, but I could raise my voice.

On the crowded streets, an infectious, loud energy reverberated. Leading off the parade, the Dykes on Bikes roared past. Behind them, guys in leather vests blew whistles and beat drums. A huge rainbow flag followed, held horizontally by over twenty people. Marchers hoisted clever homemade signs, like:

Women love women, get over it!

This is brotherhood week, Briggs! Take a lesbian to lunch.

Suck anything but orange juice!

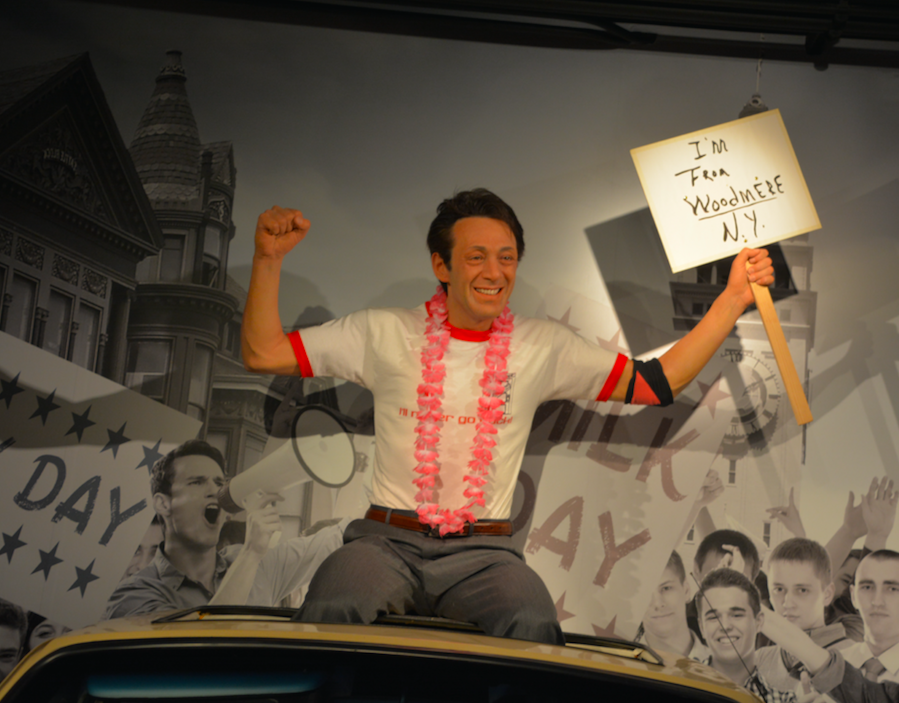

As the crowd roared, a gold Cadillac convertible inched forward, with two men perched on the back seat. Mayor Moscone pivoted, waved to the four-deep crush of spectators. I caught a glimpse of his broad smile and husky Italian face. Beside him, Harvey was wearing a rainbow T-shirt, dappled with political buttons. He held a sign on his lap: “I’m from Woodmere, N.Y.” Alongside the car, supporters handed out bumper stickers, reading: CALIFORNIA COME OUT!

Steve and I waved to Harvey. He spotted us and motioned for us to join the contingent behind his car. Fugitive common sense: hide at the curb, kiddo. A split-second decision. Do I play it safe? No, it’s my struggle. Go!

We squeezed alongside government workers, dressed in a drag parody of their workday garb. I loved the queens in doctor’s white coats. Lots of cameras and police. I squeezed myself next to Steve, my face obscured somewhat by a signboard held up in front of us, which read “You’ll never have the comfort of my closet again.” My wariness of participating in any public protest couldn’t restrain me today.

Self-affirmation at last! I thought. I’m protesting again! The gay community would never go back, never again be second-class citizens, or hide in the shadows. That day was our West Coast Stonewall, and I didn’t miss it. I was still a hunted fugitive, but in that moment I didn’t feel alone, or hopeless.

At the Civic Center rally, it was difficult to hear Harvey’s speech on the podium, given the enormous crowd that overflowed the square, but I did catch these words: “We are coming out to tell the truths about gays, for I’m tired of the conspiracy of silence, so I’m going to talk about it. And I want you to talk about it. You must come out. We will not win our rights by staying quietly in our closets.”

The momentum of the parade carried us through the summer to the November election. After the polls closed, I celebrated at a raucous party at Steve’s apartment. The Briggs Initiative lost by a million votes. 75% voted against it in San Francisco. We were on top of the world.

*

All of that came crashing down on Monday, November 27th.

My neighbor and close friend, Stan, showed up at my house. He hung his head. “The Mayor and Harvey Milk were murdered at City Hall,” he said. He told me that Dan White, another supervisor, had shot them both. Why he did wasn’t clear “but that doesn’t matter.” My young life had unfolded in a time of assassination—Dr. King, Malcolm X, the Kennedy brothers, Fred Hampton. I remembered the ominous silence in the streets, the helpless grief which moved some to helpless fury. The unthinkable must be happening again.

A grave-faced TV announcer filled in the details. Dan White avoided the City Hall metal detectors by climbing in a basement window. He went to Mayor Moscone’s office. Witnesses heard shouts followed by gunfire. Then, White walked down to Harvey’s office and shot him five times. This madman had killed someone whose hand I’d touched. Someone I admired. Our gentle hero. I sobbed in Stan’s arms.

“I’ve heard there’s going to be a vigil in the Castro,” Stan murmured. “I want to take you. Let me be your buddy tonight.” He produced two long church candles with little foil handles. “Get dressed and wrap up good.”

Before we left, I ran to the garden, where I cut off the last of my purple asters. I tied them together with a string, then climbed into Stan’s old Jeep. We found a parking spot off Dolores Street.

A mass outpouring of grief awaited us at Market and Castro. We threaded our way through the crowd, which grew by the minute, to a makeshift memorial topped with a rainbow flag. I lay my asters on top of a heap of flowers, pictures of Harvey and the Mayor, and handwritten notes.

Stan and I held hands. Backs and shoulders in front of us heaved, voices hushed to a whisper. As the sky turned dark, thousands instinctively coalesced into a line headed towards Market Street, a spontaneous march of sorrow. The police didn’t hinder us. They stood back to let everyone go.

“City Hall. City Hall.” The word passed like a rope from hand to hand.

Stan reached in his pocket for our candles. He even remembered to bring matches. A tall drag queen with mascara running in a jagged line down her cheek sang in a rich baritone. I knew the song well, the same one I sang with a maverick group of angels, as we surrounded a pyre of burning draft files in 1969, gripping our fear, as the police sirens approached. We shall overcome. We shall overcome someday.

The few cars on Market Street swerved aside, disappearing on side streets, horns silent. The electric street cars, buses, all stopped. Homeless men with shopping carts clapped, not knowing what else to do. More marchers joined, some carrying signs they’d improvised at home. R.I.P. HARVEY AND GEORGE.

No peace tonight, but no violence. Everyone respected who we were mourning, who we were honoring. We trudged along, following the thousands, moving slowly.

After nightfall, we arrived at City Hall, where the Mayor and Harvey were cut down. It became a universe of candle stars. Stan and I wedged near a street pole. The crowd grew and grew beyond the square, beyond the bare silhouettes of trees. Stan took my hand, holding it lightly in his.

Joan Baez climbed the granite steps of City Hall to a makeshift microphone. She pulled her guitar across her chest, her pale face framed by jet black hair.

She said softly, “I dedicate this song to Mayor Moscone and my friend Harvey Milk. It’s the last canción of a great Chilean musician, Violeta Parra.”

I hummed the wistful melody, as many did, all of us swaying side to side. Stan learned the song “Gracias a La Vida” through the squeezes of my hand. It’s a song about life that’s ending, crickets, birds, and a lover’s tender voice.