Queer Artist Virginia Zamora Is Painting Her Life… And Yours

The excruciating beauty of modern femininity.

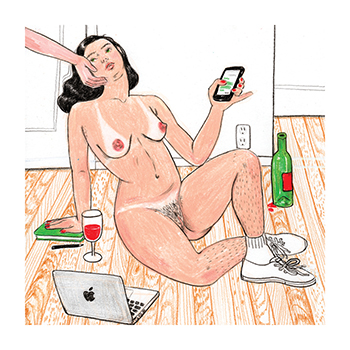

Spit and scratches. Sweat and selfies. Bruises and breasts. Blood and bikinis. Hairy legs and hot sex. Do I have your attention? Virginia Zamora sure has mine.

Virginia Zamora is a queer badass artist incorporating every deliciously sensual and uncomfortably real millennial experience into her drawings and paintings. She is an artist in every sense of the word, from the way she speaks, to the way she paints, to the way she draws, to the way she lives her life. Zamora’s career began with graphic design. Though she’s regularly drawn in her sketchbook since childhood, her illustrations weren’t public until 2017, after her work gained popularity online. When her Instagram following grew to 15 thousand and counting, Zamora’s confidence as an illustrator grew, and she became a full-time freelancer. Since then, she’s self-published a children’s book called “Hey Zoey! Get Off Your Phone!” and managed a range of commercial work, most notably a mural for Spotify’s 2018 Miami Pride celebration.

Now, Zamora continues to combine all the skills she’s acquired as a multi-hyphenated artist, entrepreneur, and creative consultant. Her last creative consultation was for Holyrad Studio’s Kickstarter and successfully raised over $50,000 for a second location. In addition, Zamora hosts and curates an annual birthday show every March featuring local New York artists and friends. Artists are not required to pay a submission fee or forfeit a percentage of sales, as Zamora feels strongly that artists need to create opportunities for other artists. She recently accepted a job as a Senior Art Director at an ad agency.

I had met Virginia on the GO float at WorldPride 2019. Okay, fine, I didn’t meet her; I just stared at her ass for 12 straight hours (so did everyone). Dressed in black pants and fishnet stockings and topped off with a full-body harness, she was definitely the highlight of our float. But beyond her gorgeous exterior was an even more beautiful mind and talent.

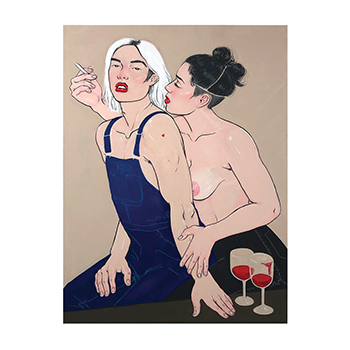

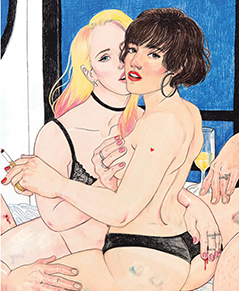

After seeing her first solo show “I’m Sweaty, Come Thru” at The Storefront Project, I found myself spellbound by the way she depicted femininity, pain, sex, and longing. Through a series of portraits, Zamora observes her own life and that of those closest to her. Depicting the spectrum of relationships that bleed from romantic to platonic in the queer community, Zamora paints the world as she sees it, surrounded by empowered women living in the disconnected dating reality of 2019. Hypermodern in its depictions, but flawless in its execution, Zamora’s work is the perfect balance between the perfect messiness of our lives and the imperfect meticulousness of an artist. It’s sort of the way that I want to write: edgy and deep, but accessible and raw. Looking at these jaw-dropping portraits, hearing their stories laced with lust and pain (it’s hard to decide between wanting to cry or cum), one might be shocked to learned that Zamora created and put together her first solo show in just three weeks.

I met Zamora on a brisk afternoon in Dumbo for rosé and a two-hour-long interview. She strutted in wearing a pale purple cropped tube top and mom jeans (only extremely cool people can pull off mom jeans). We talked mercury retrograde and swapped coming out stories, and she lifted the curtain to her artistic process, specifically what it was like to prepare for her first NYC solo show in only 21 days.

Virginia Zamora: Isn’t it, like, every planet is in retrograde right now?

Dayna Troisi: My prosthetic fell off when I was walking in here, and I’m like, “It’s Mercury retrograde.” It’s never fallen off my body in my life but it was like “SPLAT.” Some crazy shit is going on; it’s not your normal retrograde.

VZ: [Laughs] I felt so powerful yesterday, but then I was just, like, “feelings?”

DT: [Laughs] What’s your sign?

VZ: Pisces. That’s a very important question. What’s your sign?

DT: Leo! Were you always an artist? How did you come into yourself as an artist?

VZ: Always an artist. I used to get in trouble for drawing on top of my parents’ drawings at home. Always, always—ever since I was eight. My parents wanted me to be a dentist or a rich man’s wife, but it didn’t work out that way.

DT: And were you always interested in drawing and painting women?

VZ: My journaling started when I was around eight, and I remember my earliest drawings were my sister and I being punished for something. I would literally draw me and my sister crying, along with maybe two or three sentences about what had happened. Everything has always been very autobiographical, therefore naturally surrounding the women in my life. For a long time, it was this abstract narrative of what I was telling myself, and then it started becoming my friend’s narratives. I just felt it was more interesting to be authentic.

DT: I completely agree. That’s why I could never jive with writing fiction. It’s such a talent that I wish I had, but I’d much rather just pull from life.

VZ: Yeah, because that’s really where the meat is.

DT: Would you say you pull a lot of inspiration from your childhood, or is it more of things just happening in real-time?

VZ: You know, it’s interesting. Me and my therapist have gone over it: it’s a very acute coming of age time that I like to draw about. There’s a sweet spot when you’re 18 where it’s just, like, you’re becoming an adult. It’s probably because I left everything I knew when I was 18 to move to New York.

DT: And you were born in Miami right?

VZ: Yeah.

DT: And did you have a plan for New York or did you just, like, “YOLO?”

VZ: My parents obviously didn’t want me to come. They operate from fear and I get it. They were just like, “You’re going to get pregnant. You’re gonna fail.” And they love me, and I know they were saying that out of love. The reality is that I was terrified. I only applied to one school, the School of Visual Arts. I got in, I got financial aid, and I busted my ass.

DT: Icons only. How do you identify, and how would you say queerness informs your art?

VZ: I identify with she/her pronouns. I’ve never felt comfortable with calling myself bisexual. I also don’t like the terminology pansexual. So to answer your question, definitely queer. Feminine men excite me, masculine women excite me. I like being very masculine myself. I guess what I love about queerness is the element of play. I feel like, as artists, we’re constantly in that space where we’re questioning society. Underneath the queer label, I get to question my relationships with my platonic friends that often become sexual and then slip back into something platonic. That happens a lot in the queer community. We can also maintain relationships with people that we’ve been sexual with, and I admire that.

DT: So would you say that ebb and flow of how relationships change is part of your work? You had mentioned that you only paint and draw people you know in real life.

VZ: And sometimes it’s out of my head, completely. The last drawing I did was out of my head, but it’s a scene that I remember. It was just this man that was entertaining me and a friend and we were like, “We kind of just want you to leave.”

DT: Oh, the one with those two women with the big lips who were like “eh?”

VZ: Yeah, like, “Now? We can’t handle this.”

DT: I’m obsessed with that painting. I’m really drawn to paintings of women that intersperse modern iconography, like selfies and phones and colloquialisms and things like that. I have my MFA in poetry and I was always taught “Don’t do modern things. Don’t put a Diet Coke in your poem, no one will know that in the future.” And I was like, that’s what’s happening to me now. I think about Valfre, and Polly Nor, and Amber Carr, and all these women artists that very much represent what’s going on with women now. So I’m interested: did you have to break away from the way that you were trained at SVA? What inspired you to break rules?

VZ: School is hilarious. I did not paint the way that I paint now in school. And I was actually told all the time: “You have to do this. You have to do that. You’ll get jobs if you do this.” My senior year, I ended up getting two mentors, and it made me realize that what I need is conversations—I don’t need institutions. As far as dictating the branding and my art being influenced by 2019; again, I work from such an autobiographical place. I understand the beauty of something that is timeless, but I also understand that, for me, the greatest art form is humor. There’s nothing in humor that isn’t out of context. Everything has context. Whether it’s political, whether it’s narcissistic because of the selfie lives that we live right now, it’s important to, at least for me, incorporate into my work. I came from being an illustrator to fine arts, which means I’m essentially a storyteller. Brands are a big part of our lives. Andy Warhol and a lot of other people have pointed at that kind of iconography in the past, and those are the kinds of pieces I relate to. It’s like, oh there’s a phone there, there’s a this there. I want [my work] to definitely be a staple of my time.

DT: Can you tell us a little bit about your process, especially in regards to the huge number of paintings you created in three weeks? That f*cking blew my mind when I was looking at that.

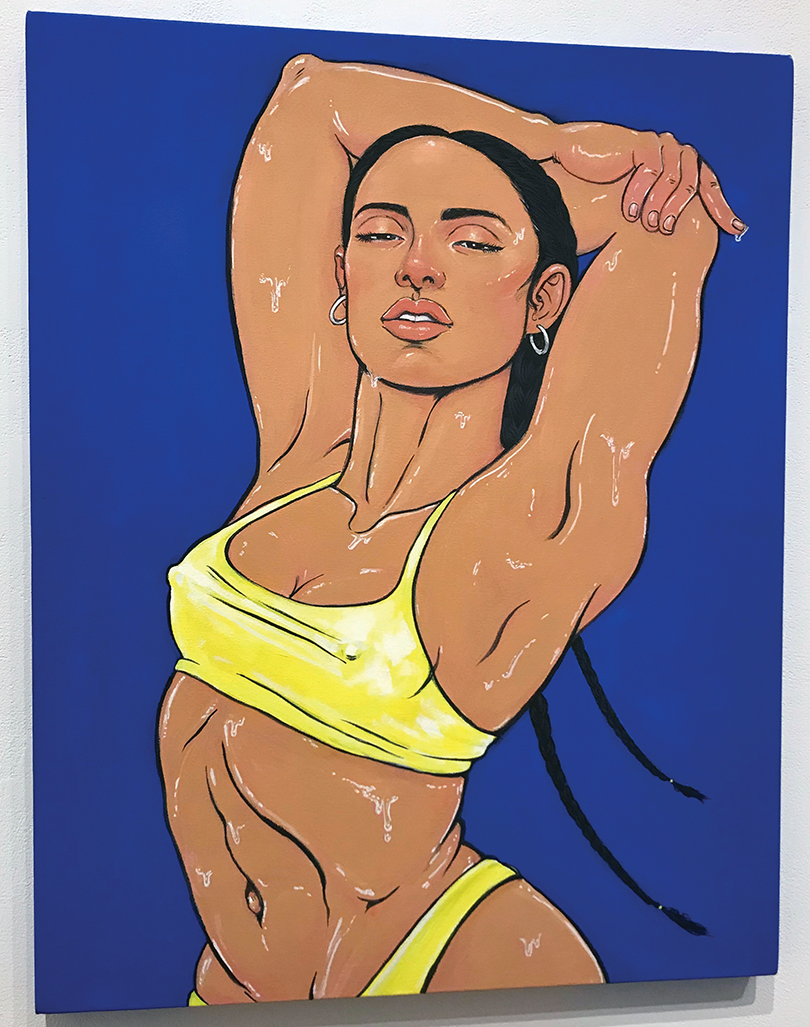

VZ: Yeah, it was insane. I would think: What is the story I want to tell of my friend? What is the story I want to tell myself? How is it that I want the audience to feel or engage at this moment? Sometimes I take polaroids of my friends. And the important thing for me is I have to fall in love with whoever it is that I’m drawing. I have to care so deeply. If not, I can’t care about the painting. There was a moment that I wasn’t in love with the girl in the red bikini, and once I gave her the attention that she needed, I was just like, “Oh, I know what this story is.” Or, for example, in the last piece “Waiting For You To Leave,” I was having a hard time naming it. I often name before I paint, because it dictates the narrative. I name things based off conversations I hear, text messages I get; It’s interesting. And for that one, that was weird because the image informed it. I started developing it, and I was like, “Oh, my god, I’m gonna put a cigarette here.” I remember when I shifted the bottom figure’s eyes to something else—so she was glancing forward—I was like: that’s the story. We’re waiting for you to leave.

The three weeks was insane. So I essentially got the show and I was like, “I see you, Universe!” You’re f*cking out here for me, you’re looking out for me. This woman was like: “Do you want to do it in three weeks?” And I’m like, absolutely. I got into the space and had a complete breakdown. It’s huge. I know size doesn’t matter, but all my work is 6 inches by 6 inches.

I’ve always wanted to have a solo show in New York. I actually said that and wrote it in my journal every day for two months, and then I got it. And I was like, “I’ve always wanted to do big paintings!” Straight up: I got a new credit card, put myself in credit card debt, and for those three weeks, I just spent the money that I wanted to spend, created the routine that I’ve always wanted, and created the work that I’ve always wanted to create.

DT: And did you ever feel stuck? Or did you just slay under pressure?

VZ: Slayed under pressure.

DT: I can tell, and that’s just mind-boggling that you did that.

VZ: I couldn’t stop. And once I came up with a rhythm I was like, “Okay, we can do this. We’ve got this.” And then I would start working on multiples at the same time and giving each one their moment. It’s very much like a relationship.

DT: That’s so cool. I know there were a lot of skin lesions and burns and things. I know you had told me that it’s kind of like representing emotional pain in the physical, but can you talk a little bit about that?

VZ: I feel like people think that I’m definitely deep in the BDSM community. … But there’s so much emotional pain. My mom used to hit me, and I would get weirdly upset that it didn’t leave bruises. Because I didn’t think it was real.

DT: Yeah, that’s really powerful.

VZ: I used to draw on top of my skin when I was a teenager. I would put a little smear of lipstick, a little bit of green eyeshadow, and then it looked like a bruise. And it wasn’t to show off to anyone: I liked looking at it by myself at my home and being like “Oh, that happened.” And I think that so much of this 2019 culture is, like, ghost culture, getting over it, when we don’t realize the lesions, the pains, the bruises that past lovers have left us. So sometimes, we’re just reacting to pain; we haven’t taken a moment to look back at a trauma. We kind of just compress it. I also think that—my best friend Tina has highlighted this—I think that I do have a lot of rage against people that take advantage of someone’s vulnerability and someone’s openness. A lot of queer women have that narrative, especially with men, and the ways that they’ve harmed them. I’m very tough on [men], and then I have to remember that I do have male relationships in my life that haven’t harmed me. Not romantic, but platonic. And even with women as well, it’s just like everyone has their shit. I wish we could all see it.

DT: Yeah, definitely. I loved the painting of the man and he had scratches all over his body. And I liked that because the scratches were kind of a part of his body, and it wasn’t like “this happened to him.” It was like, “This is his personhood, and this is part of it.” It was such a beautiful piece of work.

VZ: Exactly. It’s about his mother passing away at 17, and all those things that I could describe to you, but you got it essentially.

DT: Can you talk about your family?

VZ: I remember cutting off my hair at 18, my mom crying and saying “I can’t believe you’re doing this to the family.”

DT: [Laughs] And has your relationship improved? You said your family came to the show.

VZ: They did! It’s just kind of like, they’ll never understand, and that’s okay. I’m just trying to have that relationship with them. The way that I describe it to my therapist is that it’s like dragging two lame horses up a mountain that don’t want to go up a mountain, and they also want me to go the opposite direction, and I just need to kind of loosen the rope, but still hold on, and just have that unconditional love where I’m leading them.

DT: That’s beautiful and sad.

VZ: Sad and beautiful and gorgeous.

DT: Speaking of your family coming to your show, what’s it like to watch people observe your art in real-time?

VZ: Uncomfortable. [Laughs] Uncomfortable and really beautiful. Beautiful for women specifically. For people who really get it, like, “Oh, my god, you see me! That’s amazing! Thank you!” My gay friend who brought his partner was like, “I’ve never been attracted to a woman, but I felt the wetness, and I felt the sadness and the longing.” If I can communicate that by being super, super authentic to a gay man, then great, that’s on point. Other people misdiagnose it, or just think I’m horny. I get it, I am horny, but all women are horny. Right? You understand that? I grew up with this hunger in my belly, and it was never satisfied. My parents didn’t tell me anything, because Cubans don’t communicate about sex, but I was horny as a kid. I wanted everything and everyone, and I used to deny it because I thought it was going to make me less of a person.

DT: How do you think that plays out in your art and relationships now?

VZ: I’m giving myself visual permission all the time. And it’s interesting, because now people think I’m such an expert at this. Like, “Oh, you’re so good at polyamory,” or “You’re so good at this,” and I’m like, it’s hard. It’s hard to have that when you have that suppressed narrative in the back of your head that you’re worthless. Like, wow, you’re worthless to this husband and this mother-in-law that you’ll never meet.

DT: Not to be this interluder and make this about myself, but I find that I felt the same way when you’re a writer and you’re constantly writing about sex. Like, I don’t know, sometimes I can’t even believe I made it this far, because I never thought I would have a voice or do any of this, let alone have success with it. I think my parents have definitely come around, and they’re so proud of me now, which is amazing. It’s funnier, just to be open and talking about it, and I’m sure you feel the same way being open in painting and drawing and erasing that anxiety. And actually being successful and having people respond to it is tremendously rewarding I imagine, and f*cking exciting.

VZ: I have the perfect story, actually. This Marine DM’s me on Instagram one day. I saw his profile and he had two pictures, all of them were with guns and, like, 17 other white guys. And he was just like “I want you to know something.” And I was like, “Word? What?” And he was like, “You made me so uncomfortable and what that has caused me to do is look inside and realize that a woman’s beauty is hairy legs and having a period.” And I was like: “I got through to you? Give me your address right now.” I sent him an original and it was just, like, I need to infect these people and these environments that are made uncomfortable. If I’m able to penetrate that man—I use the word penetrate often, I realize—then I’ve succeeded. That is success.

DT: That’s amazing. And I think that helps with our common humanity, too.

VZ: Yeah, you wouldn’t expect that that man is getting it from anywhere else. If I can leave this world where Madonna and whore are the same person, and that’s someone you should still value, then that would be my success.

DT: That’s badass. What would you say the biggest challenge facing women artists today is?

VZ: Being taken seriously. There’s so much art out there, especially street art that depicts women. And to not have that from the female perspective is dangerous. It’s just dangerous. Because, first off, we’re capitalizing on women’s beauty, and men are seeking the benefits of it. It’s hard to be taken seriously. You know, there are guys right now in my life who have the opportunity to buy my work. And I know that they only want to buy my work because they want to be like “Oh, I’m gonna take you out to dinner and talk about it.” And I’m like, “My work is like $5,000. If that’s legitimately something you want to do, then that’s something I would consider.” But then it starts to bleed into this area of, like, oh, do I owe men shit? And then women that I want to buy my work, I almost want to give it to them, because it’s like, if you can’t afford it, but you’re the one that needs it… You know the Gorilla Girls said it best in the 80s: “I’d rather have my work for free in a college dorm room than out in a museum.” And I’m struggling as an artist, and in real-time, trying to walk that tightrope. I don’t know if that’s the biggest challenge facing women, but it’s hard.

DT: What has been the biggest triumph of your career so far?

VZ: Probably that Marine, to be honest. I always think about him, and I get really emotional. That, and kind of de-stigmatizing ideas around period blood and sex and a woman’s appetite for sex.

DT: What is your biggest goal moving forward?

VZ: God, pay rent! And drink Pina Coladas.

DT: [Laughs] Can I get that tattooed?

VZ: Yes! I have such simple wants in this life. I want to do art without compromise, and be taken seriously. I also want to uplift women. The first show that I curated here in New York was no submission fee, no percentage of sales. I put up all the money to have women’s work on the walls. It was 25 women for my 25th birthday and, like, that’s what I want to do. Especially because the art world can only be infiltrated with people who have pre-existing wealth.

DT: I was at the Guggenheim the other day and there was this beautiful exhibit with all these nude photos, but then I thought, “Okay, but there are so many sex workers and women doing the exact same thing on Instagram, taking the same kind of photos and getting flagged, and like, what makes this have a deserving spot?” What makes this art and the others not? Not that it didn’t deserve the spot, it was beautiful in its own right, but like, to see nude women get censored on Instagram and have their shit taken down, that is just infuriating.

VZ: Very infuriating. The tragedy of what’s happening with sex work right now, especially in the trans community, is heartbreaking. I can’t really speak much more than that, but just like, the women in my life who have experienced the shame and not being able to get work, in any kind of job, in any kind of field because of the way that they present. You know, humanity is so cruel [that] sometimes I feel like we’re all kids in f*cking sandbox again. The way that I try to understand it is just like, “How is this hurting you? How is the reflection hurting someone else?” And I feel like that’s a really good narrative for my work. I’m just holding up like, why can’t you see this? Why do bruises make you so uncomfortable? Why does a woman’s sexuality make you uncomfortable? That’s really the conversation I’m trying to have. I feel like, with queer and trans women, it’s often not about us, it’s about other people, and it’s hard to not realize that and recognize that in the moment.

DT: Have you had issues with censorship on Instagram? I know Instagram has really been cracking down on art depicting female nudity.

VZ: Not yet. I had one thing taken down, but it wasn’t my art, and you know, c’est la vie. I really like having shows for that reason. My other business is curating these phone-free dinners. As much as I want to point to social media for getting me this show and getting me other things and establishing that relationship that I had with that Marine and with other women, I want presence. Come to a show. Let’s have that conversation. Get off Instagram and into a space where you can feel dangerous. If you want to explore your sexuality, go to a BDSM course. Go by yourself to a bar and pick up someone that you’ve never picked up before. I’m always the first person to go up to someone and be like “I think you’re so attractive,” even if it’s just a compliment and that’s where it stays. Women need to take that initiative more because I think the shame around “Oh, I’m going to seem like I’m easy, I’m going to seem like a slut”—no. People really respect that. Male or female. Get into the driver’s seat of your life.

DT: Yeah, I always think that. If someone came up to me in a bar and was like, “I think you’re so sexy,” I would, like, jizz my pants. Why am I so scared to do that to someone else?

VZ: I do that all the time. Make yourself uncomfortable.

DT: You caused quite the stir shaking your ass on GO’s float at WorldPride back in June. People worshipped you and went so nuts for you. You got us so many followers, so thank you. But what was that day like for you? I feel like that was a day that we were all connected to each other.

VZ: That day was insane for a lot of reasons. My opening was that Thursday, so I hadn’t really been sleeping; maybe I slept a couple of hours. I’m riding this high of life, and I’m wearing what I wear to my BDSM circles: my bulldog harness. I was wearing something super masculine and then those garters.

DT: The stockings were iconic.

VZ: The stockings were iconic. I had never had stockings that didn’t cover my ass, and I actually bought the wrong ones. Fun fact. And I was like, you know what? If I wasn’t on the high of my show opening, if I wasn’t on the high of a lot of things, with my best friend being in town and seeing my outfit and being like “yass bitch,” I don’t think I would have worn that. The fact that I did and the fact that I wanted to show up for the community is because I wanted to make myself uncomfortable, going back to our previous question. I didn’t want to play it safe, because I know that I often—I think it’s from being an older sibling, I have a younger sister—I often just want to lead by example. And you can’t tell someone that they’re beautiful if you don’t feel that yourself. What I received that day was so incredible and so beautiful. That day was really liberating.

DT: Thank you for dancing the entire time. What does Pride mean to you?

VZ: Something that makes me uncomfortable. And something that I’m trying to embrace more and more of every day. Last year, I was asked by Spotify to do a mural about gay pride for Miami, and it was the first time that I called my parents and told them I was gay, because I never wanted to make them uncomfortable. I don’t use my real last name in my art because I don’t want to bring down this empire that they created for themselves. I’ve had so much shame. At the same time, in my position as someone that liberates women visually, I need to start embracing my role. If you are, in any way, in any small influence, being looked at by 15 women, and you encourage queer women to be more themselves, you need to show up in a way that makes you uncomfortable. And do your research. So when I think of Pride, I am so proud to be who I am. I am so proud to be with women, and I am so proud to be with the men that I am with as well. I want to always create space in my work for that world, because it’s given me so much freedom.

DT: That’s perfect. Part of GO’s mission is uplifting queer women, creating something that a little queer girl in bumblef*ck could just see a woman succeeding and be like “I’m out, and I do this.” So, is there any part of your coming out story that you feel comfortable sharing? Thinking about a young girl that would be looking at your art, and just thinking, “Oh, my God, I wish I could be like Virginia.”

VZ: When I was 12, I kind of knew I was queer. I started telling everyone when I was 15. I started embracing it in college, but I didn’t tell my parents until 25. Their immediate reaction was, “Why does everyone have to know? Why can’t it be a secret?” And I feel like all parents are slightly narcissistic, because they’re just looking at themselves. They’re scared for you, and they’re worried for you. I just remember telling them, “I’m posting it on Instagram, and I don’t want you to hear it from anyone else. I’ve been like this since I can remember.”

I think that they’re doing their best to forget it. The reality is that I’m showing up for myself, and I don’t live in Miami anymore on purpose. There are a lot of people that think that bisexuality or me coming out is for them, especially men. There was a lot of my life that I had to keep so private, because I didn’t want people to misunderstand what that meant, which is why I always felt so uncomfortable with a label. I’ll never forget when I was fifteen. I told a girl, a friend, that I was definitely into women as well. The next day, she spread a rumor that I was in love with her and that my hands smelled like fish from putting them in so many vaginas. And I’m like, well, that’s one way of going about it. It’s hard. It’s a lot of shame growing up, especially in my community. They’re like “Oh, you’re a lesbian, because you like performing for your husband. You’re sexual because you like being sexual with your husband.” I remember when I was 18—God, I was actually older than that—I was 22, and I got out of my college relationship with a man, and I didn’t even realize that I was still continuing that narrative post-college. I was so horny, and that’s actually where my work started from. I was so horny and I was like, what do I do? I’m not with Leo anymore, and I’m like, wait, I have myself. I didn’t feel comfortable acting upon it on my own. Even though I had at that point, and I had after. And I remember the disorientation after three years of being in a heteronormative relationship and then realizing that the narrative I was trying to escape my entire life I was doing. And he was also a bisexual man. He’s now with a man, and him and I are great friends, and that’s the beauty of the community.

DT: Can you talk a little bit about how queerness intersects with your Cuban identity?

VZ: You know, there are obviously gay Cubans. But I didn’t really have a representation of that in my family.

DT: So you didn’t have queer role models to look up to growing up?

VZ: Not at all. And that was really tough. I remember Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl” came out and I was like “What? Is this mainstream?” I was like, “What?” I was very lonely for most of my life. So I would draw.

DT: What artists serve as inspiration to you?

VZ: This is where it gets interesting, because there are a lot of men that I point at. John Cuneo is a complete pervert. Shantell Martin is an incredible queer artist from London who I’ve recently met, she works from a stream of consciousness. Robert Rodriguez [is] an incredible director who works with no money and just tries to get movies done and, like, I get it; I see that hustle. God, whose art do I look at? It’s kind of sad that we’re so overly saturated that I can’t think of five more names. I’m not thinking of enough women, especially queer women. My friend Claire Merchlinsky.

DT: If you could speak to every young queer woman artist in the world, what would you tell them?

VZ: Be yourself. Be authentic. When you see moonlight or read a story. The only thing that people really connect to is when they’re like, “Oh man, that is so real.” Then they will be able to place their own narrative in it, even when it has nothing to do with them.

And also, be mediocre. There are definitely things with my paintings where I’m like, “Oh, I could have done this better.” But just start. Don’t make it unachievable.

DT: Is there anything you would want GO readers to know that we haven’t touched on?

VZ: As queer women, we show up for our family, show up for our friends, and don’t show up for ourselves. But if you use a 10th of that energy, and show up for yourself, you will be able to achieve those three things on your to-do list that take twenty minutes each, and you will feel so much better about overextending yourself. I don’t really know a woman who has achieved that balance to a T yet, and, when I do, I’m like, thank you for living as an example for me. It’s so easy to overextend ourselves. Send some of that love to you, because men do it all the time. I want to be a rich man. That Cher quote is my f*cking mantra. I want to be a rich man, bitch.