Paris. Late 19th and early 20th century. Quite a few affluent men led double lives: outwardly respectable by day, seekers of erotic titillation at brothels and café cabarets by night. Commercial wealth created by the French Empire bankrolled a sophisticated capital city, which could only be dreamed of elsewhere. But it was the women who brought this dreamworld to life.

In Paris, intolerance towards the talented wasn’t in fashion; and so queer culture flourished. Private literary salons were hosted by well-known lesbians like Nathalie Clifford Barney. Some of the crème de la crème entertainers were lesbian or polyamorous – the dancers Jane Avril and May Milton, the internationally famous actress Sarah Bernhardt, the circus clown Cha-U-Kao, and “La Goulue,” the star of the Moulin Rouge, the most famous cabaret in Paris.

Young women earned very little money as dancers in the corps de ballet or as artist models. Hardship drove many to become sex workers and courtesans: an existence, for some, marked by destitution, substance abuse, and obscurity; for others, marked by success and acclaim. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) immortalized many of these women in extraordinary drawings and paintings.

Much like the women he painted, Lautrec was always an outsider. Born into an aristocratic family, Lautrec inherited a congenital disease. After he broke both his legs as a teenager, he never properly healed, remaining a dwarf for the rest of his life. Already feeling different from those around him, he turned to the study of fine art and moved to Montmartre, the bohemian district in Paris. His highly productive life was spent largely among nightclub performers, sex workers, and hangers-on. He died at the age of thirty-six from complications of alcoholism and syphilis.

In popular culture, Lautrec is often portrayed as a drunken poster painter, but that’s just Hollywood fiction. Rather he was a consummate professional who produced over 700 paintings, 5,000 drawings, and sculptures in a career lasting less than two decades. He moved in the most advanced intellectual circles and invented modern techniques of printmaking. His style is exemplified by radically simplified forms, acute caricature, and bold areas of brilliant color, which owed much to Japanese woodblock prints fashionable at the time.

Like no other artist, his drawings openly reveal the secret life of sex workers, many of whom had intimate relationships with each another, finding some emotional comfort and stability in a profession that offered none at the time. He presents real life lesbian sex workers holding each other in bed, kissing, and embracing – in these paintings, it is clear they weren’t performing sex acts for the viewing pleasure of male clients.

Who were the lesbian, queer, and polyamorous women of the cabaret and theatre in Lautrec’s famous lithographs and posters?

Jane Avril (1868-1943)

Born in Paris in 1868, Jane Avril was the illegitimate child of an Italian marquis and a Parisian courtesan. A chaotic childhood led to confinement for a time in a mental institution. After her release, she trained as a can-can dancer and became famous at the Moulin Rouge, Jardin de Paris, and the Folies-Bergère. In the early 1890s, she met Lautrec. She’s a prominent subject of some of his most important works — twenty paintings, fifteen drawings, many lithographs and posters between 1891 and 1899.

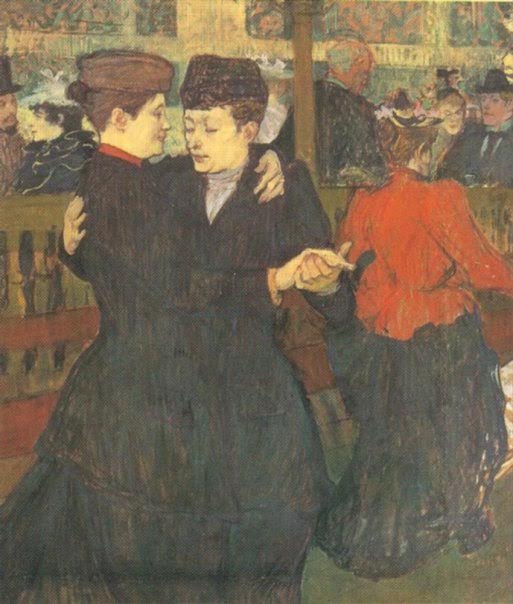

Jane Avril had educated herself, becoming a refined, witty woman, and the darling of famous poets. She fell for the English performer, May Milton, with whom she shared an apartment in Montmartre. Although Lautrec never depicts Jane Avril in a manner explicitly identifying her as a lesbian, she’s featured in works with openly lesbian content. Lautrec’s lithograph “At The Moulin Rouges, Two Women Waltzing” shows the lesbian Cha-U-Kao dancing with an unknown woman, while Jane Avril stands right behind them in a red jacket.

One Lautrec lithograph acutely captures the juxtaposed reality of the dancehall versus the dancer’s life. A favorite of mine — Jane Avril in a tangerine-colored dress. She’s performing a high kick with her arms lost amongst voluptuous ruffles. Avril appears birdlike in her frenzied movements. Yet her expression is one of sadness or perhaps exhaustion, but clearly at odds with the glamorous setting.

Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923)

Sarah Bernhardt was the greatest international stage actress of that era, “the Divine Sarah,” the symbol of France herself.

The daughter of a Jewish courtesan from Amsterdam, her mother’s hustling secured her an excellent convent education. She trained at the Conservatoire in Paris, then as a bit actor at the Comédie-Française, but was fired because of her fiery temper. Unemployed, she turned to the streets like her mother, and eventually gave birth to an illegitimate son.

Those few years on the corner fueled her passion and stage presence. She was rehired by the Comédie. From there, and over the course of a very long career, she starred in every major theater in Europe and America making dramatic leading lady roles her own (including Shakespeare’s Hamlet).

She performed as she lived: an intense femme fatale who never tired of sex with a long list of who’s-who male lovers. Her only stable intimate relationship was with a woman — the lesbian artist Louise Abbéma. Abbéma became Bernhardt’s official portraitist with a flood of commissions from wealthy, fashionable clientele. Abbéma possessed, like Bernhardt, a certain je ne sais quoi. She was brash, smoked cigars, and dressed in men’s clothing. She was the life companion and confidante of Bernhardt for fifty years until the actress’s death.

In 1898, Lautrec completed a lithograph of Bernhardt in the role of Cleopatra, perfectly capturing her over-heated passion, fragility, and authenticity that she brought to her roles and to her life. Lautrec portrays Bernhardt in a full-on dramatic moment from the final act of Shakespeare’s play. Bernhardt’s arms are thrust upwards, her sorrowful eyes ringed with copious black eyeliner, her mouth sagging downward in despair.

Cha-U-Kao (dates unknown)

Cha-U-Kao was a French entertainer who performed at the Moulin Rouge and the Nouveau Cirque in the 1890s. Her stage name was derived from the French word “chahut” meaning chaos, a reference to the bedlam of high-kicking can-can dancers.

Little is known about her life, including her real name. Cha-U-Kao was a gymnast before she became a famous female clown. She wore a distinctive black-and-yellow costume and had her hair piled up on her head.

She was depicted in a series of paintings by Lautrec and became one of his favorite models. The artist was fascinated by this woman who dared to choose the male profession of clowning and wasn’t afraid to be openly lesbian. Lautrec sometimes sketched Cha-u-Kao with her partner, “Gabrielle the Dancer.” He included this lithograph in a series devoted to the theme of sex workers, called “Elles.”

La Goulue (1866-1929)

Louise Weber was destitute, obese and drunk as she lay dying. “I don’t want to go to hell,” she told the priest. “Father, will God forgive me? I am La Goulue!”

Her stage name, “La Goulue” meant “The Glutton,” referring to her habit of guzzling cabaret patrons’ drinks while performing. It was a name with the power to evoke a whole era, and La Goulue, this Queen of Montmartre, stood – or rather kicked, as the star of the can-can – at its epicenter. La Goulue was born in Paris in 1870, her father a cab driver, her mother a laundress. Like so many others, this comely working-class girl became a sex worker and artists’ model, before debuting as a dancer at the new Moulin Rouge. There she mastered the can-can, a dance originally reserved for courtesans. She was soon drawing a crowd of crown princes and captains of industry, attracting fame and francs in equal measure. After a few years she was emboldened to leave the Moulin Rouge to do shows independently.

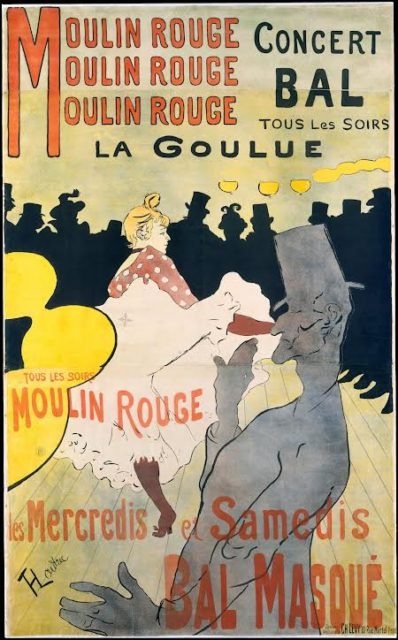

She openly flouted her relationships with women. In 1891, she was immortalized by Lautrec in one of his most famous posters, an advertisement for the Moulin Rouge on the streets of Paris. She also commissioned him to paint two huge backdrops of the Moulin Rouge which are freeze frames of Paris by night. One of them features the artist himself at a table with Oscar Wilde, the famous Irish playwright and gay man who was about to go on trial in England.

La Goulue could never recreate her Moulin Rouge success. Eventually the backdrops were cut up and sold in pieces. What survives has been pieced together and displayed prominently at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. And La Goulue, no less broken up, took ever more menial jobs. At the end, she was living in a caravan among rag-pickers, seemingly forgotten.

Lautrec made La Goulue a star for the ages in a single poster that made him famous overnight. La Goulue dances at the Moulin Rouge. She kicks her leg in the air, boldly, tauntingly, ignoring the silhouettes of her dancing partner “No-Bones” Valentin – known for his extraordinary elasticity – and of the rapt audience watching in the background.

Lautrec is considered the iconic painter of bohemian Paris during the Belle Époque, which Catherine van Casselaer (Lot’s Wife: Lesbian Paris, 1890-1914, Janus Press, 1986) aptly dubbed “the undisputed capital of lesbianism”.

Lautrec never patronized his subjects, never romanticized them, never made judgments, but showed them as they were. Lautrec understood the grit of life, the grinding reality of being a sex worker, that tenuous life built on youth and beauty, and the fate of outcasts.

What Do You Think?