From climate change denial to the growing anti-vaccine movement, this anti-science trend is alarming, to say the least. It’s high time we celebrate—not condemn—science’s part in our history and the amazing individuals whose research and work revolutionized how we live our lives today. The history of science, however, is all too often remembered as a little too male and a little too straight. Sure, we’re as grateful for the resurgence of ‘90s favorite Bill Nye The Science Guy as the next person, but let’s take a minute to celebrate the LGBTQ scientists that history often forgets.

From household names like Sara Josephine Baker and Sally Ride to unfairly forgotten figures like Louise Pearce, the work of LGBTQ scientists remains majorly influential today. The women below didn’t just fight to save coral reefs, help develop treatments for life-threatening diseases, and educate the public about basics of personal hygiene we take for granted today. They also advocated for other women and minorities in their field, pushing for a more diverse and accepting scientific community overall. So, let’s give them a round of applause and take a minute to celebrate the accomplishments of these LGBTQ scientists.

Sara Josephine Baker

Physician Sara Josephine Baker was instrumental in developing the modern concept of preventive medicine. Early in her career, she became concerned with the lack of healthcare and public education in low-income neighborhoods in New York City. In 1917, she was disturbed to learn the infant mortality rate in the United States was higher than the mortality rate for soldiers fighting in World War I. She led a public education campaign to teach parents proper infant care, including basics of personal hygiene not widely known at the time. While her effects on the medical community remain heralded today, a lot of people forget about her personal life. While Baker never publicly identified herself one way or another, she had a female partner, novelist Ida Alexis Ross Wylie, during the last years of her life.

Sally Ride

Prior to making headlines for being the first American woman in space, Sally Ride obtained a Ph.D. in physics from Stanford University. After wrapping up her astronaut career, she worked at her alma mater for years as a researcher and led a variety of public education programs encouraging young kids to get into science. After her death in 2012, many were surprised that Ride’s obituary noted she had a female partner. Ride’s sister confirmed the relationship and noted Ride had preferred to keep most of her personal life—including her sexuality—private. However, she was open about her sexuality in her personal life.

Ruth Gates

The rapidly disappearing nature of coral reefs is a depressing but well-documented fact of 21st-century life. Marine biologist Ruth Gates played a major role in both understanding coral reef ecosystems and educating the public about the threat climate change places on these oceanic wonders. Prior to her death in 2018, her life’s mission was to help save coral reefs by deliberately breeding “super corals”—reefs that can withstand higher sea temperatures. Gates’s tactics are still being implemented today as scientists attempt to strengthen coral reefs worldwide. If successful, this could potentially prevent the extinction of the species. As for Gates’s personal life, she was openly gay and married her wife in 2018, shortly before passing from brain cancer.

Sophia Jex-Blake

Physician Sophia Jex-Blake was a vocal member of the Edinburgh Seven, the first group of undergraduate female students to study at a United Kingdom university. An outspoken feminist, Jex-Blake actually led the campaign to allow her group to enroll in the University of Edinburgh. After graduation, Jex-Blake had a successful medical career. She became the first female doctor in Edinburgh and continued to advocate for medical education for women throughout her life and career. She was romantically involved with fellow doctor Margaret Todd throughout most of her adult life, and the pair moved to the country together upon retirement.

Margaret Todd

If we’re going to mention Sophia Jex-Blake, we’d be remiss to exclude her partner. Margaret Todd was an accomplished doctor in her own right and even helped coin the term “isotope” (look it up). She graduated from the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women and had a successful career in medicine and science. However, she found a penchant for creative writing as well. She published several well-received works of fiction that dealt with medical and scientific themes. After Jex-Blake’s passing, she wrote the nonfiction book “The Life of Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake” to help preserve her partner’s legacy.

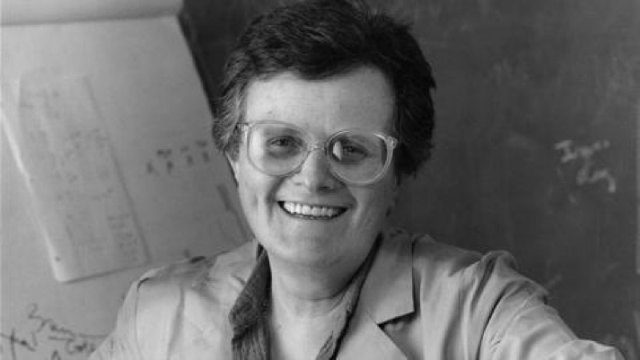

Neena Schwartz

Endocrinologist and outspoken feminist Neena Schwartz joined other well-known LGBTQ scientists after making a number of groundbreaking discoveries about the female reproductive system throughout the 1980s. In fact, some of her research helped doctors eventually develop ways to screen for diseases like Down Syndrome during pregnancy. An outspoken member of the feminist movement, Schwartz pushed for more female representation in the science and medical community. In her 2010 memoir “A Lab Of My Own,” she publicly came out as a lesbian. Schwartz felt it was essential to be open about her sexuality, as she wanted other LGBTQ scientists to feel represented in the community.

Agnes E. Wells

Agnes E. Wells started out working as an educator in Michigan’s rural Upper Peninsula and climbed her way to the top of the academic ladder by the late 1930s. She served as the Dean of Women at Indiana University, where she taught as a professor of mathematics and astronomy. Women scientists (let alone LGBTQ scientists) and educators were a rarity at the time, and Wells was an outspoken advocate for women’s rights. A member of the National Women’s Party, she fought for women’s rights to vote and went on to push for the passing of the Equal Rights Amendment. She even established a $1 million fellowship fund for the American Association of University Women. Throughout much of her career, she was romantically involved with fellow educator Lydia Woodbridge, who taught French at Indiana University. Wells and Woodbridge lived together until Woodbridge passed away in 1946.

Louise Pearce

Pathologist Louise Pearce paled around with other LGBTQ scientists of her time, including the aforementioned Sara Josephine Baker. She was a member of Heterodoxyh, a feminist bi-weekly luncheon had many bisexual members including Pearce herself. As a scientist, she was best known for developing a successful treatment for African Sleeping Sickness, a serious epidemic at the time that had devastated various regions in Africa. After receiving the Order of the Crown of Belgium for her work, she went on to help develop treatments for syphilis and research the growth and spread of cancer tumors.

What Do You Think?