On May 7, 2012, Krista Sturgeon ate a simple breakfast of two scrambled eggs and toast. Hardly a memorable feast under ordinary circumstances, but for Sturgeon the breakfast marked a milestone: it was the most she’d eaten at one sitting in nearly twenty years.

Sturgeon had suffered from an eating disorder since the early 1990s. After two decades bouncing between hospitals and two near-death experiences, she’d finally had enough. “Something clicked. I told myself, ‘I got myself into this, I guess I will have to be the one to get myself out.’”

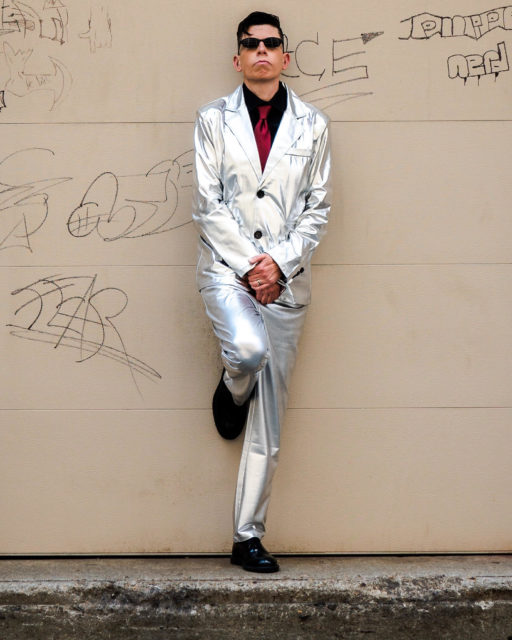

Now fully recovered, Sturgeon is determined to use her experience in order to help other LGBTQ individuals who suffer, often silently, from eating disorders. She’s recently launched the Mira Alto Foundation, a non-profit organization that advocates the proper treatment of patients on the LGBTQ spectrum. The goal of Mira Alto: to ensure all eating-disorder patients, regardless of sexuality, sexual identity, age, or race, are treated with respect and dignity when seeking treatment.

The relationship between sexuality, sexual identity, and eating disorders is still in the early stages of scientific recognition. Only a handful of studies identify the sexuality of their participants, and fewer still have focused exclusively on LGBTQ individuals. However, a general consensus suggests that LGBTQ persons may be more susceptible to eating disorders than their heterosexual or cisgender peers. According to the National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA), LGBTQ persons may be susceptible due to fear of social rejection, bullying, trauma from violence, or the inability to conform to socialized body ideals or the body type of their perceived gender identity.

Treatment options for LGBTQ individuals can also be problematic. LGBTQ individuals may lack not only family support but also competent care from medical practitioners. Treatment centers that specialize in eating disorders don’t always train staff to recognize the needs of LGBTQ patients, or to recognize stressors that stem from sexuality or sexual identity. Additionally, many LGBTQ patients who seek treatment may be reluctant to open up, for fear of being marginalized. Even something as simple as signing a legal name can be traumatic for transgender individuals, and a potential roadblock to them seeking help.

It’s an experience that Sturgeon knows far too well. A self-identifying lesbian, she believes her sexuality prevented clinical staff from providing her with the care she needed. “They didn’t know what to do with me, they didn’t know what to make of me.” An androgynous female, she didn’t fit the hyper-feminine stereotype of an anorexic. She was sometimes excluded from group therapy for fear she might make others uncomfortable by mentioning her girlfriend. Some doctors assumed her emaciated body to be a symptom of HIV. They’d refuse to recognize her as anorexic, and would instead shuffle her off to yet another hospital, psychiatric ward, or, in one case, a nursing home.

But Sturgeon isn’t interested in judging treatment centers for what she endured, or for their current approach to LGBTQ patients. The goal of Mira Alto, Italian for “aim high”, is to work with treatment centers to ensure that medical staff know how to address the particular issues facing patients on the LGBTQ spectrum. Sturgeon plans a comprehensive outreach to centers across the country, first by assessing their current protocols for treatment and then by offering training for improvement where necessary.

Launched in August of 2018, the foundation is still in its early stages. Sturgeon is currently at work building a matrix to assess treatment centers through both online surveys and on-site visits. She sees herself as an advisor, having Mira Alto partner with centers to increase awareness of and sensitivity to the unique problems facing LGBTQ individuals. “Like a restaurant inspector,” she says, before adding, with a smile, “but without wagging fingers. We go in and help them fix the problems. It’s a win/win situation.”

Since her recovery, Sturgeon has spent the past four years working for eating disorder advocacy. In 2017, she worked in community outreach for Project Heal, a non-profit organization that helps patients pay for treatment. The organization honored Sturgeon at its 2018 Boston gala.

“Krista is extremely passionate about the work she is doing to improve access to treatment and quality care,” says Arwen Turner, chief operating officer of Project Heal. “I admire her fearless approach to breaking down the barriers she finds to her organization’s goals and her willingness to help like-minded organizations make diversity, inclusion, and access to eating disorder care a priority.”

“Fearless” would certainly describe Sturgeon’s approach. In 2017, she conducted a body positive demonstration in New York City’s Union Square for World Eating Disorders Action Day. For two hours, she sat blindfolded in her underwear next to a placard that asked pedestrians to draw hearts on her body in a show of support for those afflicted with eating disorders. When asked how many hearts were drawn, Sturgeon couldn’t say. “There were literally too many to count! It was amazing!”

Eventually, she wants Mira Alto to advocate for other underserved and marginalized groups at risk for eating disorders. While she does believe that most treatment centers are trying to improve, she also acknowledges that there is work to be done.

“There can be nothing worse than what I went through,” she says, and from statements like this it’s clear her sentiment stems from the very real and terrible fear that many of us face: that in moments of crisis, when we are at our most vulnerable, we won’t be taken seriously.

It’s this fear that Sturgeon thinks keeps minority and underrepresented groups from seeking the help they need when dealing with eating disorders. “People don’t get treatment because they’re scared, or ashamed. If I could say anything to anyone with an eating disorder, I’d say, ‘Be brave. Come forward. There are people who will help.’”

Krista knows. She is one of them.

If you’d like to know more about the Mira Alto Foundation, please visit the website at https://miraaltofoundation.org/.

What Do You Think?