The Right to be Gay

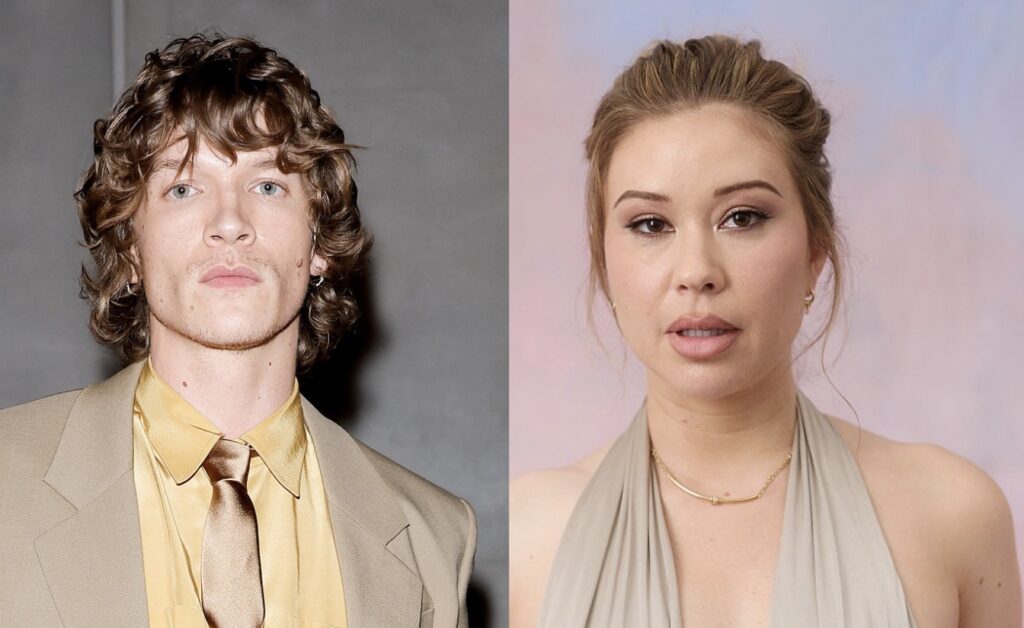

Blue Jean explores surviving as a lesbian in Margaret Thatcher’s era.

Novelist Richard Price once said that the trick to writing about major societal issues is picking “the smallest manageable part of the big thing, and [working] off the resonance.” Director-writer Georgia Oakley’s Blue Jean is a poignant manifestation of these words set to the melodic instrumentation of Amy Green and the Solem Quartet. The film follows PE teacher Jean (Rosy McEwen) as she navigates the complex world of being gay in the increasingly anti-LGBTQ+ political climate in the UK of the 1980s (Margaret Thatcher’s England).

At first, Jean is simply surviving the day-to-day. She forces herself to be okay with eating alone in the teachers’ lounge. A stranger shouts homophobic slurs at her as she walks to a gay bar to hang out with her friends. It’s a testament to how queer folks find a way to go on no matter how hard life gets. Then a new student by the name of Lois (Lucy Halliday) arrives and suddenly everything Jean has learned to settle with is put to the test.

Blue Jean is at once a reminder and a call to action. In this world, Jean is slowly buckling under the pressure of surveillance and the expectation that any little thing she does can be used against her. When she encounters Lois, her instincts are so hostile that they eventually drive a wedge between her and her girlfriend Viv (Kerrie Hayes). At the same time, Lois is also struggling to come to terms with her own sexuality. The two are at their best when they come to realize that they are in this together. The chemistry between the actors is seamless and almost makes the audience feel like voyeurs in someone else’s most private moments.

Community is such an important aspect of being queer. It’s a means to sharing resources, intergenerational bonding, and having a safety net to fall into during the process of coming out. More importantly, community is how lonely queer folks come together while being targeted with aggressive anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Jean doesn’t always make the right choice, and Lois is one of the people who ends up hurt because of that. But the power of community pushes them both toward a level of bravery only possible when one knows they aren’t attempting it alone.

Oakley may be new to the world of directing feature films, but her camera movement speaks of experience. It’s direct and straight (no pun intended) to the point, but always carries an underlying softness. The audience isn’t meant to judge Jean for her choices, but to empathize with the cold reality that made them feel necessary in the political climate of the ‘80s. The only enemy is the homophobic government.

The storytelling of Blue Jean is simple yet dynamic as it effectively marries the politics of the time with the story of a woman just trying to get by. It also speaks to Oakley’s goal of “[holding] a microscope up to the small things that keep Jean awake at night, in an attempt to reframe the discussion on bigger issues such as homophobia, patriarchy and class that plagued the UK in the 80s, as they do now.” At the end of the day, Blue Jean is a remarkably simple story about “resisting the shame regime” and embracing one’s “inalienable right to be gay.”

There’s a reason why Blue Jean (an apt double entendre) has taken several awards on the international festival circuit, including last year’s Venice Film Festival (Giornate Degli Autori’s People Choice Award), Thessaloniki Film Festival (Best Actress), and the Belfast FF (Breakthrough Performance). It’s out in the U.S. on June 9.