For Women’s History Month, GO is celebrating LGBTQ women we wish we could have learned about in high school history class.

Most exhibitions and discussions about Dadaists focus on the men of the movement, like Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali. But women like Hannah Höch not only forced her way into the misogynistic boys’ club in Berlin, but publicly commented on it in her work. The bisexual German artist penned an essay about her experiences in 1920 (“The Painter“) and also portrayed imagery from the women’s movement from the time in her work, sometimes even including herself among the crowd, as in her famous painting “Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser DADA durch die letzte weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands.”

An artist from a young age, Höch first became involved with the Dadaists through Raoul Hausmann, whom she met in 1915. They later went on to a have a romantic relationship that would last seven years. While her early artistry was focused on glass design, graphic arts and handicrafts, she eventually became one of the documented pioneers of photomontage. A lot of her work during the Weimar Republic years featured androgyny, specifically women with masculine traits often pictured doing things that were outside of their traditional gender roles. She also created the Dada Dolls, some of her more famous work.

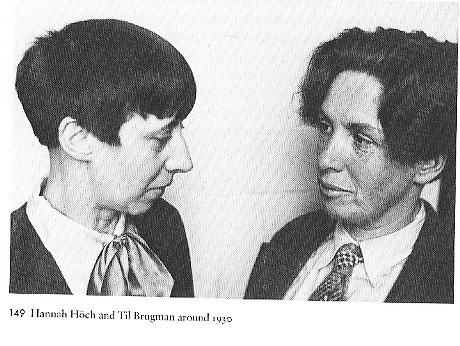

In 1926, Höch began a romantic relationship with Dutch writer Mathilda Brugman, moving to Hague to be with her until they both relocated back to Berlin three years later. The two ended their partnership in 1935, and Höch then married Kurt Matthies in 1938, eventually divorcing in 1944.

Höch’s work has been displayed in a career retrospective at The Whitechapel Gallery in London in 2014, as well as having the solo show “The Photomontages of Hannah Höch” travel the U.S. to display at The Walker Art Center, The Museum of Modern Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Political, feminist and queer, the perspective Höch offered was fresh and forward-thinking for her time, and made a considerable impact on the art world, even if she’s been all-too overshadowed by her male peers. She died at age 88 in 1978.

What Do You Think?