Italy Might Not Feel Safe For Queer People, But This Milan Trans-Feminist Bar Does

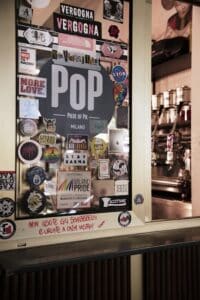

Welcome to Pop, Milan’s queer safe space in Giorgia Meloni’s Italy.

Fedya Crespolini was standing at the counter of Pop – her Trans-Feminist bar in Milan’s Rainbow District, Porta Venezia – when a 60-year-old Italian person walked in and ordered a coffee. The person sat alone watching Fedya, whose queerness is marked by her bridge piercing, her mullet and the word ‘BUTCH’ inked on her hand. As she placed the espresso in front of them, they looked into her eyes and said: “I feel like I’m a woman and I don’t know what to do.” Fedya, who was born in Milan, contacted a number of local organisations, and a couple of years later, she received a message from a trans woman on Facebook thanking her for everything she’d opened up for her that day.

This is one of a thousand stories of transformation this little street-side terrace bar – lined with beer barrels and disco balls – has facilitated since it opened in 2018.

“It’s like a little bubble inside the city,” says Trysha, a 28-year-old transwoman from Calabria, once a patron, now a bartender at Pop. “I’ve found a place where I can use my name, my pronouns, where people don’t ask why, it’s just that; here I am, there you are, you want a drink?”

All walks of Milanese life congregate in Pop’s alfresco seating area; punks, kids, fashionistas, sipping colourful cocktails and taking slices from a neighboring pizzeria. Though Pop started life under the banner ‘lesbian bar,’ the space has evolved alongside the needs of the community, first to a ‘feminist,’ and then a ‘trans-feminist’ bar. Now the majority of their staff are trans or non-binary, “I’m the last lesbian standing,” jokes Fedya, who’s 45-years-old, “and a bit of a punk,” she says in Italian.

I sit with Fedya and her partner Silvia Frau (our translator and Pop’s events manager) for several hours on a balmy afternoon in late July. It was the final night before Pop closed for the customary summer break, when Europeans vacate sweltering centers to flock to the coast. In Fedya and Silvia’s case, they were flying to Havana in the morning, a necessary getaway for two of the city’s most important queer space holders.

“There is a big social responsibility when you own an LGBT+ bar,” Silvia tells GO, whose piercing yellow eyes are hidden behind statement Milanese sunglasses. “It’s a place where people come to experiment, to ask, to try to understand the environment, and themselves,” she says. Queer bars, she explains, are often the first port of call for people who may not be ready to approach support groups, seek medical advice or come out to family and friends. They feel a similar social responsibility to hire members of the community. “Trans people still have a lot of difficulty finding work, and it’s a mission of Fedya’s to ensure people can have this opportunity,” says Silvia, adding that, “she always tries to find the most vulnerable people to hire – so she can really make a difference.”

Both note how beautiful it has been to watch Trysha’s metamorphosis in her two-year career at Pop – she literally twirls and flutters around the bar like a butterfly – “it’s so important that even at work she’s free, she doesn’t have to pretend for half the day as she would need to in other jobs, it really helps people to find their true selves,” adds Fedya.

The words ‘Trans-Feminist’ are lit up in blue and red neon lights in the heart of the bar. It is the only trans-feminist bar in Milan, and one of few explicitly named in Europe. The signage is unmissable from the street outside, acting as a beacon of increasing prominence since Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing government Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) came into power last October. The fear of a fascist resurgence is ripe in Italy, particularly among minority groups, most notably migrants, refugees, and the LGBTQ+ community, who Meloni frequently jabbed at on her rise to power. Her party, Fratelli d’Italia, was conceived from Italy’s neo-fascist group Movimento Sociale Italiano (M.S.I.), and this organization was a direct continuation of Mussolini’s Fascist Party. Meloni’s logo (a tri-coloured flame) is the same as M.S.I.’s. Meloni has also moved her Headquarters into M.S.I.’s old office in Rome. These fascist chords (which Meloni refuses to cut) coalesce with her adage, “I am a woman, I am a mother, I am Italian, I am Christian” – to send shivers down the spine of the country’s queer and ethnic minority communities.

Pop feels like a safe and vibrant haven in Milan as Trysha waltzes around in her lace bralette and flawless make-up. She says ciao, ciao, grazie, ciao, to almost everyone passing on the sidewalk, which acts as a catwalk between the bar and terrace. A nonna in a dressing gown with an octopus stitched on the front, walks her puppy down the runway. A person in lime crocs, emerald socks and teal trousers strides past, causing Fedya to stop mid-sentence and say, “I love Porta Venezia… the best area in the world.”

When Fedya opened Pop, her vision was to create the “atmosphere of the Italian countryside bars,” where local people meet to discuss politics, play cards, sip beer, “where there is a continuous exchange among the people,” she says. To centre important conversations, every week Pop hosts a night called Unpopular Opinion. “The [LGBT+] community thinks it is very inclusive,” says Silvia, “it sees itself as diverse, fantastic, very open, and that’s not always the truth. We need to discuss, again and again, a lot of things that can divide people inside our community.”

Driven by the notion that it’s easier to discuss tricky topics in a safe space “with a beer in hand,” says Fedya, Pop has hosted heated and heart-centred conversations on topics like sex work, conscious drug-use, BDSM, body positivity and living wills. They have had women who wear hijabs, talk about what feminism means to them, and in September, a nun is coming to discuss her dream of integrating Catholicism and queerness. For Pop to be the palace of political discussion it’s intended to be, they frequently invite political parties, especially in the build-up to elections.

“It’s really important in Italy,” says Silvia, “as we don’t just have the left and right here, we have a lot of parties within the left and right…”

“And Giorgia Meloni,” adds Fedya, flinging her right hand way out over the sidewalk.

Fedya is the non-gestational mother of a 5-year-old child. In January, Meloni’s government ordered state agencies to stop registering children born to same-sex couples, and as Human Rights Watch reports, this was taken to the next level in July when a state prosecutor in Padua (one of the oldest cities in Northern Italy) sent letters to the non-gestational lesbian mothers of 33 kids, informing them that they are being retroactively removed from their children’s birth certificates.

“Of course this is a direct impact for Fedya as a person,” says Silvia, “before the bar and the political fights and everything, this is the most important thing.”

It should be noted that the Mayor of Padua blocked this and continues to recognise two-mother families, and there has been no other retroactive non-recognition, “but we don’t know,” says Fedya. And it’s that uncertainty that’s pinching the nerves of minority groups across the country.

Meloni has spoken of being anti-abortion (Italian gynaecologists can refuse abortion on moral or religious grounds, and up to two-thirds do), surrogacy is illegal in Italy, IVF is only available for heterosexual couples and, in July, Italy’s parliament approved a bill criminalising couples who go abroad to have children via surrogacy. “Torture isn’t a universal crime in Italy, but surrogacy is,” says Fedya, turning her palms to the sky, shrugging her shoulders and widening her eyes in a quintessentially Italian expression of disbelief. Meloni has also controversially moved to clamp down on NGO ship’s seeking to rescue imperilled migrant boats in the Mediterranean Sea.

“And this is in ten months,” says Silvia, referring to the polls indicating that Fratelli d’Italia’s popularity remains, and has in fact increased in this period. “We’re afraid she will get elected for a second term… imagine what could happen in ten years, if this is what’s happened in ten months.”

“We are very afraid,” Fedya concurs.

That fear doesn’t directly correlate to the running of Pop, where a bust of Björk watches over the bar, Beyoncé’s Alien Superstar blazes from the soundsystem, and Melissa, Pop’s chief mixologist, free pours tequila over ice. City laws regulate the bar, so there’s a buffer between Meloni and Fedya’s queer haven. “Still, I do feel the true impact on the community,” she says, “people are feeling very unsafe on the streets… there seems to be more empowerment to harass others,” says Fedya.

While sitting on Pop’s terrace, two clothed and six unclothed police officers blaze down the runway, like a blast of icy wind. “There is an issue; and this is not something that we want to deny,” says Silvia, “with micro criminalità (petty crime), it happens a lot in Milan, especially here in the nightlife district, where people are drinking, having fun, not caring about their wallet.”

The city unleashes more police on the streets in an attempt to remedy this, she explains, but as is the case across nations, “the police are meant to be helping but if they intervene with a person from a minority group, there are different prejudices and consequences,” she says, mentioning Eritrean people and trans people, because Porta Venezia is the cultural hub of both communities (a bar called Addis Ababa is a stone’s throw from The Rainbow Café, for instance).

“The police definitely feel empowered by this government’s talk and policies toward minorities,” says Fedya. That icy breeze as the police rolled through Pop, froze over the area in May, when Bruna, a Brazilian transwoman of colour, was pepper sprayed, kicked and beaten by three police officers while she sat on the floor, her hands in the air. The devastating incident sent shock waves through the community, solidifying the importance of the Rainbow District Association, a blossoming mutual support network of LGBTQ+, Eritrean and Shisha bars in the area. They work together on many issues; keeping the residential community content (by signing agreements on 2am curfews), pooling together to reduce plastic waste, and lobbying to get the refugee/migrant youth off the streets and into the system. “In general, we try to not involve the police,” says Silvia, noting that if there is an issue with someone from the Black community, for example, they ask the Eritrean bars to intervene. Likewise if there are issues with, for example, a queer/transgender person, they help. “We organize amongst ourselves, especially if there is a big event like Pride, we train and pay people to help with the security side,” she adds.

I’m visibly taken aback by the scope and social responsibility of this queer bar.

“Yeah,” Silvia says, “it’s not like having a bar, sipping gin & tonics,” she raises an invisible glass to her lips, “it’s a lot more complicated than that, believe me.” Silvia looked at Fedya and they both laughed. It is clear that the palpable love they share is an anchor, allowing them to fight for a more equitable Milan.

After our interview and a bit of partying at Pop, we exchange our goodbyes and I amble the 20 minutes to Milan’s Centrale Railway Station. All the terraces are full of Italians taking long sips from their sunset aperitifs. The train station is staggering in size and grandeur. A greying white, brutalist structure with sculpted art deco features, it’s 72 metres high, 200 metres wide, and dwarves everything around. The striking facade was the brainchild of Mussolini, who wanted a structure to represent the power of his National Fascist Party (who ruled Italy from 1922-1943). The station is all bulging muscles, bald eagles, naked men and winged horses. And then I notice the symbol of Mussolini’s Fascist Party (a bundle of rods tied around an ax, a Roman symbol of power). The same bundles frame Mussolini’s grave.

I look around at the life buzzing at the station’s feet; people with skin of all shades, walking fast or hanging around waiting for trains, or friends or nothing in particular. A police van loaded with armed officers to my left, kids, families, a cute queer couple hand-in-hand.

As I watch, my mind hums with the insights of two lesbian activists and lovers, from a lesbian mother and from a transwoman who’s found her queendom at Pop. I wonder what Milan will look like in four years time, as Meloni’s first term draws to a close. Trysha’s words float to the front of my consciousness: “It’s dangerous, and it’s expensive, but it’s my place. I found myself here, I feel like home.”

I wonder who Giorgia Meloni believes has the right to call Italy home. I wonder what she thinks when she looks up to this greying statement of Italian Fascism, contrasted to the diversity of the people going about their lives underneath. I board the train, heading north to Switzerland. The window like a cinema screen, hurtling past the countryside of this conflicted country, another dollop of contradiction in this divided world. I feel a deep and profound sense of gratitude for Pop: that Milan’s LGBTQ+ community has a place like this, a place to call home.

Pop Milano

Via Alessandro Tadino 5, Porta Venezia

Open daily 6:30pm-2am

Follow: @pop.milano