When I read your work, I see clear instructions: Be direct, be unapologetic, be deliberate.

One of the most important lessons I learned from you in my twenties was to define myself. You said, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” This prompts me to continue to self-assess and own my identity, particularly as someone who can be mistaken for others — as someone who is read as heterosexual, middle class, and as any number of other markers. There is less room for assumption when we clearly and emphatically define ourselves.

It is not enough to just be when we are working for change in the world. Systems are rigged against some of us because of who and what we are, and we cannot confront or change them without naming the factors that lead to our oppression and exclusion. I see your intent in naming yourself, defining yourself, time and time again.

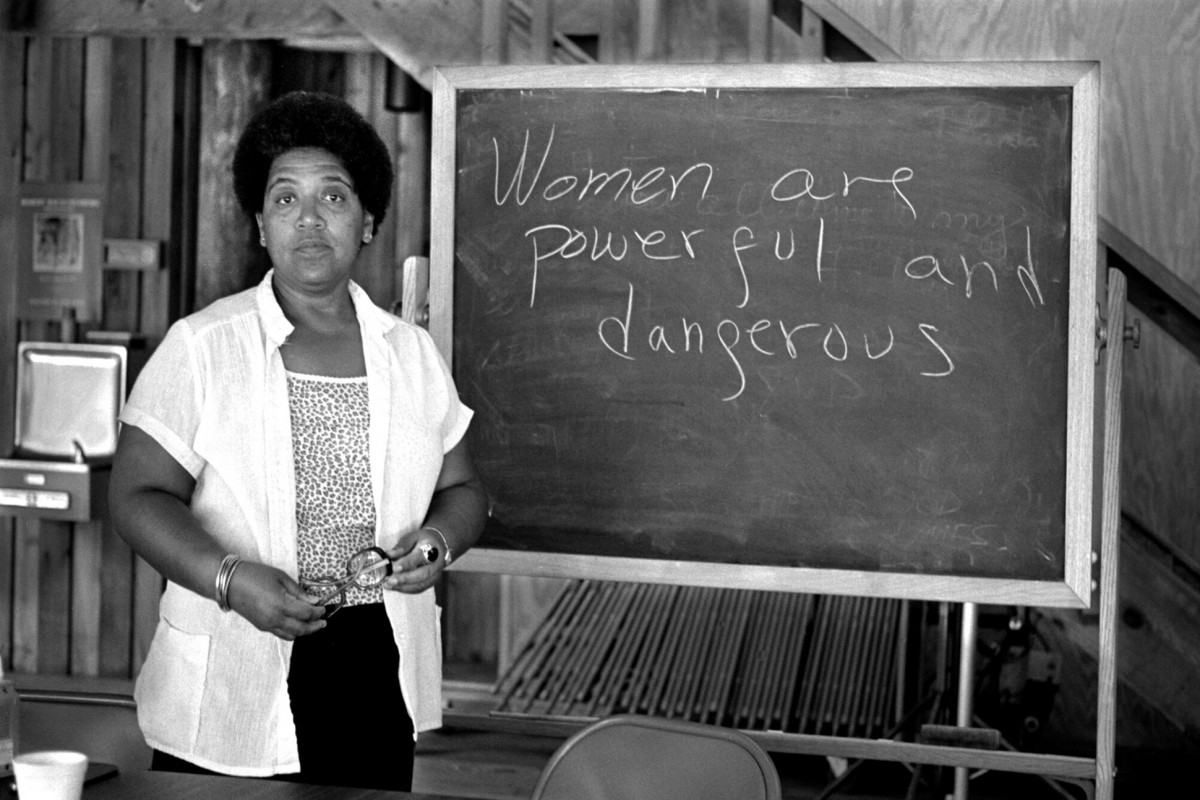

You are one of the most referenced Black queer activists, and it’s no wonder. You were brilliant and bold. You defined yourself for yourself, gave your identities names, and demanded that the world wholly acknowledge you. You gave us a model for creating freedom.

You didn’t wait for anyone. You made space for yourself, challenged the status quo, and left us with poetry, speeches, and essays that would, for decades, inform, shape, and accelerate our activism.

You noted, “I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.” As you probably predicted, your work is misused by vultures whose only purpose is to sell themselves as experts, boost their platforms, and silence marginalized people. Instead of diligent study, they quote you out of context, sometimes to support positions that are harmful to your own identities. I have been on the receiving end of this harm.

You are revered as an activist and poet, and it is infuriating to see your words used without recognition of your sexuality which you intentionally named over and over again. Homophobic people have quoted you in attempts to silence me, not knowing who you were. I must admit that I take great pleasure in asking the people who lean on your wisdom, “Did you know that Audre Lorde was a lesbian and she said so often?” and “Did you know she said we don’t live single-issue lives?”

When I think of you — and I think of you often — the word “and” comes to mind. I look at you — your work, your energy — and I see and, and, and. Your life and work are a lesson in sitting in the fullness of who we are and how we came to be. You were always intentional in the claiming of your identities: woman and Black and lesbian and mother and warrior and poet. You recognized that these identities not only shaped you but dictated your experience of the world and interactions with people until you learned to push back.

I know, more and more every day, who I am. I say the words every day because you taught me that I need to know, remember, claim, and affirm my identity. I am Black. I am woman. I am queer. I am unwaged. I am never just one of these. I am Black and woman. Woman and queer. Queer and unwaged. Because I sit in these identities, reflect on my own experiences, and read your work, I know that it is no mistake that my life is complicated by these intersections. I know that I am never one thing, and I learned that I cannot simply focus on one cause. They are all related, intertwined, interdependent. I cannot be a free Black queer woman if Black people, queer people, or women are not free.

I am grateful to you because I am so frequently told to wait, to let other people go first, to follow protocol. I can’t and I won’t. As a queer Black woman and a women’s human rights defender, I refuse to allow queer women to be forgotten and excluded in the name of “progress” for women who get to be just women.

I remind myself that “Life is very short. What we have to do must be done in the now,” because it can be tempting to settle for incremental change. Sometimes we feel like we just need a small win, but in those times, I choose the radical act of rest. You told us, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” It is true in many ways. For me, it keeps me from settling. It keeps my demands where they should be: high.

I have become more deliberate in my observation of my own position, “learning how to take [my] differences and make them strengths” as you suggested in “The Masters’ Tools Will Never Destroy the Master’s House.” In the speech, you called out the organizers for their lack of attention to a specific group of people experiencing multiple oppressions, unconcerned about expectations of humility or gratitude for being included.

“And yet, I stand here as a Black lesbian feminist, having been invited to comment within the only panel at this conference where the input of Black feminists and lesbians is represented,” you told them. You took up space. You addressed issues without softness. You prioritized truth and justice over politeness and comfort. You showed, over and over again, that it is necessary for us to name wrongs and hold people to account. It was you who reminded us that silence does not guarantee protection, and fear is not a good enough reason to refrain from speaking up. You encouraged us to be loud; to be vocal; to demand that people hear us say exactly what they are doing and challenge them to change.

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” people say, repeating your words. They do not often include the following lines from your speech. “They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.” These are just as important because they warn us against leaning on the wrong resources and systems. With these words, you urge us to create our tools. You told us that community is the only way to liberation. That is what kept me from falling into the trap of educating white people when the Black Lives Matter protests started earlier this year. That is what helped me to decide to put my focus on building community, creating spaces for dialogue, prioritizing healing, and thinking about the longevity of the movement for Black liberation.

Your work is still with us, to be read, studied, and spoken. There are always words of yours to inspire the best parts of ourselves to emerge and respond to our highest callings. I am pleased when people know your name and parts of your work, but I do not congratulate them for the bare minimum. I call attention to your identities. I do not let them eclipse your named identities — Black, lesbian, woman, warrior — with those they deem most acceptable or redemptive. I tell people they cannot weaponize your words — the words of a poet and activist — against me because you thought them, wrote them, said them for me, a Black queer woman warrior. We, the people at the intersection of multiple oppressions, build on your work, call you by name. As you continue to teach through the work you left for us, we demand visibility and space as we claim and wield the power of difference. Because we know who we are, who we can be, and we can be free.

You have helped me to see myself, show myself, align myself with people like me and fight for justice for all of us. I have deep gratitude for you and the work you did, now part of the foundation of my advocacy. I thank you for your vision, for your sharing, for your boldness and brilliance.

We will be direct. We will be unapologetic. We will be deliberate. You said so, and so it will be.

What Do You Think?