Early on Friday, May 30, folks gathered at the famed Stonewall Inn to hear Sally Jewell, Secretary of the U.S. Department of Interior, announce that the National Park Service is launching an initiative to identify historic LGBT sites. The evening before, just blocks away, hundreds had gathered to celebrate the life of one of our movement’s heroes, Stormé DeLarverie, who passed away May 24.

Although she was a true gem of our community, many LGBT individuals have no idea who Stormé DeLarverie was, nor do they know of her contributions to our movement.

Best known by her first name, Stormé, she was born in New Orleans in 1920 to a white father and a black mother, and as such was never issued a birth certificate. Though light-skinned, she always identified as black, as a way to honor her mother.

Stormé presented as a masculine lesbian and had no time for what she referred to as ‘ugly’—in other words, people being rude, disrespectful and mean. She was a fierce defender and protector—a warrior. She was known to carry a handgun or two, and was remembered by many as more than just security at local watering holes in the West Village.

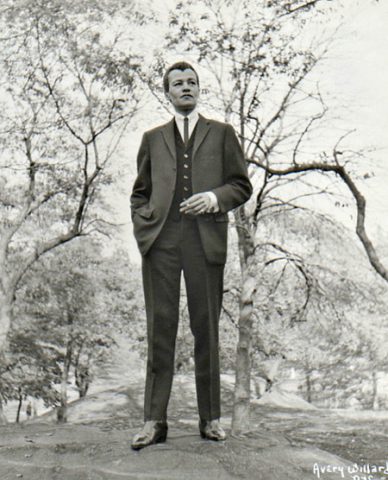

For decades, Stormé performed with the legendary Jewel Box Revue, a touring company of female impersonators. (She was the act’s sole male impersonator.) In 1987 a film by Michelle Parkerson, “Stormé: The Lady of the Jewel Box,” captured Stormé’s life in the 1950s and 1960s touring the black theater circuit. During those decades, she was photographed by Diane Arbus and Avery Williard.

In the 1969 Stonewall rebellion, Stormé played an integral role. Her confrontation with police at the Stonewall Inn during the early morning hours of June 28 was considered a flashpoint in the riots, igniting the crowd to fight back. Later she would become a founding member of the Stonewall Veterans Association.

Stormé lived an incredibly rich life and never turned her back on our community. I wish that I could say the same was true of the community in Stormé’s last years.

In 2010, while facing housing and legal issues, Stormé took a bad fall. As a patient at St. Vincent’s Hospital, where she received care, she underwent testing to determine that she was also battling dementia. I had the pleasure of finally meeting her during this time, when my friend Lisa Cannistraci (the owner of Henrietta Hudson and a longtime community activist) called me hoping that my former boss, Congressman Jerrold Nadler, might be able to help Stormé.

At the time, the Jewish Association for Services for the Aged had become her guardian. Stormé was now living far from her community and with much concern, Lisa—along with Michele Zalopany, a resident of the Chelsea Hotel—began the process to obtain legal guardianship.

The congressman connected Lisa and Michele with attorney Peter J. Strauss, who in 2012 was named New York City’s Elder Law Lawyer of the Year. With his help, Lisa and Michele successfully became Stormé’s guardians.

Stormé was transferred to Cabs Nursing Home in Brooklyn, and for the final years of her life, visited by a handful of dedicated and committed friends. In recent years, Stormé received honors from Brooklyn Pride, Inc., New York City Black Pride, and just a few weeks ago, the Brooklyn Community Pride Center.

But I believe that a funny thing happened on the road to equality. We slowly began forgetting those who paved it.

Much like Stormé’s dementia caused her memory to dim in her later years, the rich histories of our elders are fading from our consciousness. People who celebrate the LGBT movement’s victories forget the roles our elders played in making them possible. We, as a community, by failing to care for, protect and befriend our elders, are leading ourselves down a path in which these phenomenal lives and stories will be forgotten. If we forget our own history, we are doomed to repeat it.

Looking around the room at Stormé’s memorial, something struck me: I saw longtime friends of Stormé’s, but what I noticed largely missing was my generation. And while mourning the death of a hero, I struggled with feelings of anger and frustration. Where was my generation? Where were our elected officials? Why did almost a week go by after Stormé’s passing until a major publication reported on her death?

I spent the weekend connecting with friends in the community my age, mentors who knew Stormé. I was reminded of how many of our seniors are without families to care for them, some living in shelters. And if the names we are reciting in chants are fading from memory, then what’s going on with the rest of our seniors?

Back in the office on Monday, I spoke with the Brooklyn Community Pride Center’s ElderPride group. I wanted to hear from them, get their thoughts on what I was feeling: that my generation isn’t showing up for our elders.

Many of our seniors agreed; many wanted young(er) people to ‘give them a chance’—and those who have participated in formal and informal intergenerational gatherings, to love them. Much to my surprise, I also noted how in many ways they too had turned their backs on the generations before, as if they were the ones who came up with the idea of gay liberation. A college intern spoke about his concern regarding technology and how it is dividing generations. Pretty much everyone in the room agreed that spaces for intergenerational gatherings to occur are critical. It goes beyond a school curriculum; it is not the mere recitation of dates and facts. We should be connecting with our seniors.

As Robert West, a longtime friend of Stormé’s, reminded those at her service, as long as we’re breathing we must honor and visit our elders. I am calling on all of us to act—to lift up the lives and stories of our elders. We represent multifaceted and rich communities, and it is our obligation to pay tribute to those who came before us. And not just those who came before whose names are on buildings and faces on stamps, but all of our seniors who in their own ways paved this road to equality.

SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders), GRIOT Circle, the Audre Lorde Project, and the LGBT Centers throughout the city have programs for elders and to connect with elders. Learn from them, honor them and tell their stories. They are too important to lose. They cannot be forgotten.

There will be a memorial service planned for Stormé in the fall.

Erin M. Drinkwater is the executive director of the Brooklyn Community Pride Center.

What Do You Think?