Sierra Leonean Trans Activist Finds ‘Home’ On The Island of Lesvos

It all started with a broken heart.

Roxy* kept her queerness to herself as she was growing up in Freetown Sierra Leone. Her mother – a pastor – was too preoccupied with her congregation to notice Roxy’s true identity; her stepfather however, became fixated by it. “This boy is gay, I am telling you that this boy is so gay,” he would proclaim to anyone who would listen.

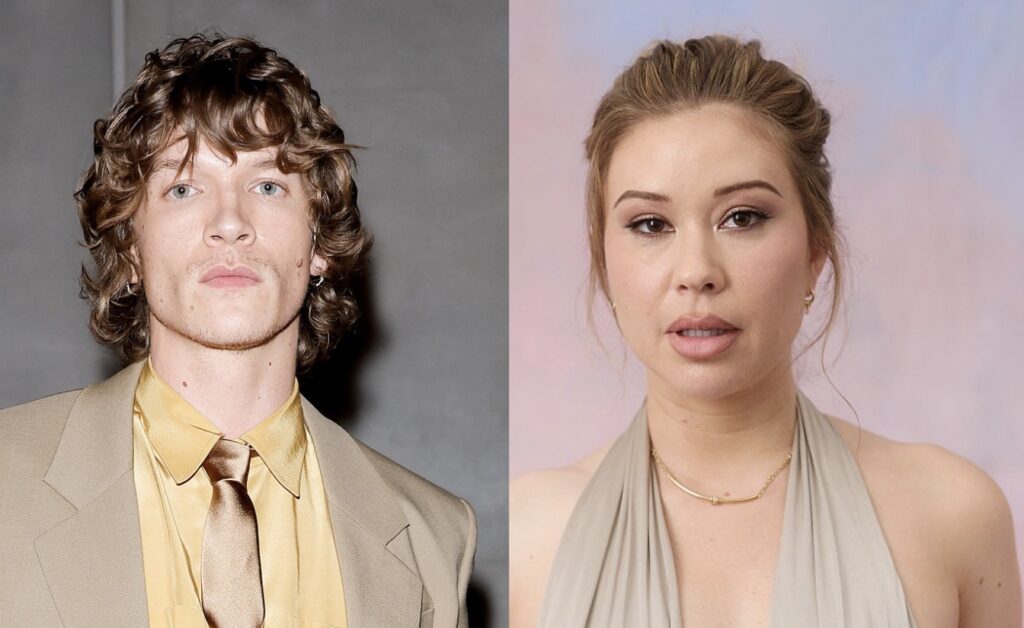

“Somehow my stepfather was the first person who actually knew I was queer, I mean I hadn’t actually done anything, but I was always so feminine,” Roxy tells GO, her model-esque features and fierce femininity radiating through her living room. Roxy is now a 28-year old trans woman, and has always known she was queer, “I was born like this,” she says proudly.

Since last October, Roxy has been staying in LGBTIQ+ Refugee Solidarity’s safe house in Mytilene, the capital of the Greek island of Lesvos. She, like many others, seeks asylum in Europe, because the risk of discrimination in her family and community was so great. In Sierra Leone, acts of ‘buggery’ (a British colonial law) carry a maximum penalty of life imprisonment for men. Though the law contains no direct reference to queer women or trans people, and there have been no recent legal prosecutions, Roxy says that queerphobia is deeply embedded in the Sierra Leonean psyche. She was outed at the age of 18 by the wife of her then lover, though no one had actually “caught” them having sex. She explains that most queer people are allegedly “caught” and then outed. “It’s all sex, sex, sex with them,” she says, “they’re going to penetrate you, they’re going to penetrate you, is such a fear in our culture.” Though the law lies dormant for now, there are regular reports of family and local communities taking things into their own hands; perpetrating assaults, blackmail, rejection, denial of basic rights and services. Roxy modestly describes her experience of coming out in Sierra Leone as “not easy,” before she shares the tragic day her family threw her out on the street and publicly flogged her with a cable.

With the rug of familial support tugged from under her feet, Roxy moved between friend’s places as her physical and emotional wounds healed, and she soon trained as a make-up artist. She started to build a small, covert community in Freetown, “of gay boys, trans women and also straight women who worked the streets,” she says.

Roxy and her trans women friends lived with a consistent threat of violence, as is the case around the world. “I was always wondering, what is the way forward for trans people in this country?” In 2017, Roxy tells GO that a transperson was “mobbed and killed” in the streets in Freetown. Roxy knew her community needed more; more support, more advocacy, more safety; so she created a Whatsapp group where transpeople could share information, advice, and before long, the Trans Alliance Sierra Leone was born. They held weekly meetings in “low-key venues,” says Roxy. They had to operate completely under the radar, often in a friendly, quiet bar, or someone’s apartment.

Lesvos LGBTIQ+ Refugee Solidarity, Roxy’s current community and home, is a similarly underground grassroots collective, incidentally launched in 2017 too. They have lively weekly meetings with their 25 members, all of whom are seeking asylum in Europe, and herald from countries where their queerness cannot live freely (namely, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, Congo, Cameroon, Haiti, Somalia, Turkey and Ivory Coast). The organisation provides an invaluable chord between lawyers, psychologists, caseworkers and the island’s queer refugee population. They help applicants to better understand procedures, help officials to better understand queer asylum seekers, work in solidarity with other LGBTIQ+ organisations in Greece, and offer emergency support and accommodation for people in their two safe houses.

View this post on Instagram

Roxy relays her life story while sharing a sofa with Ria*, one of the group’s coordinators, who moved to Lesvos a year ago from Germany, where she had lived in squat and activist communities for many years (and has the tattoos and piercings to match). Throughout our interview, the housemates sit side-by-side, singing each other’s praises and listening intently to one another, already acting like old friends.

“We’re always excited to meet new people, but we were so hyped to meet Roxy,” says Ria, noting that Roxy had written an extensive message, plus photos and videos, explaining all the activism she’d already done in her country. The Trans Alliance Sierra Leone work in collaboration with various other trans and intersex organisations in Africa, focusing on security training, recording human rights violations, providing basic amenities (food and shelter) for unhoused trans people, and emergency health systems (most significantly, accessing condoms, PrEP, and support for those living with HIV & AIDS). Crucially, Roxy adds, “in Sierra Leone, there are a lot of trans people who cannot fend for themselves if they are sick, they couldn’t go to a government hospital because when the nurses, or perhaps the doctors see them, and see that they’re queer, they’ll start spreading the news around the hospital and no one would want to touch them.”

“Life felt full for me,” Roxy says of her years in Freetown, despite the lingering danger and discrimination. She had stability from her makeup job and the life affirmation from providing support to her trans community. So Roxy was blindsided by the rapid sequence of events that led to her departure from Sierra Leone, to the island of Lesvos.

It all started with a broken heart. “My partner left me for someone in Ghana,” says Roxy, “they moved to England together and I never saw him again.” Without a loving partner, combined with the social ostracism she experienced as a queer person in her city, Roxy sought solace for her heartache in drugs. Substance abuse is common in young people in Freetown, most notably Kush and “zombie-drug” Spice are very cheap, highly addictive and easy to find in a country where two-thirds of the population fall below the poverty line. Research shows that in numerous cultural contexts, drug addiction is much higher in LGBTIQ+ populations. In the US for example, addiction rates are 30% in queer and trans people, compared to 9% in the general population.

Roxy describes the exhausting cycle of substance abuse as; “being high and calm, and then as soon as the drugs wear off, it’s like I’m starting all over again.” It had been a couple of months trapped in this loop before she woke up one morning, looked around her room, looked at herself in the mirror, and saw how lost she’d become. “This is shit,” she spoke aloud to her reflection, and she instantly got up, cleaned her room, cleaned her face, and got herself clean. Roxy hasn’t touched a substance since, a resilience that shines through her radiant smile and defiant tone of voice.

Coming back to herself, Roxy received a final blow in Sierra Leone, when someone started harassing her online by uploading photos and hateful posts about her. Lots of unwanted, venomous attention befell Roxy; someone even slashed her car tires, boys started throwing stones at her house, and all around, a dark miasma of unsafety grew around Roxy. “The country was getting smaller and smaller for me,” she says. It was time to make the same journey many of the most influential queer people in her life had made (her first boyfriend had fled to America, her trans mentor and her latest boyfriend had left Sierra Leone too). Roxy sold her car and everything she owned before boarding a flight from Sierra Leone to Turkey. From there, she made the formidable crossing to the island of Lesvos, to face the nightmarish cocktail of traffickers, thrashing waves, flimsy boats and border police illegally pushing boats back. Upon arrival, Roxy was taken to Mavrovouni camp to register as an asylum seeker – another unexpected risk point for queers, as Ria explains; “if someone states that they’re gay, the translators can sometimes tell other people in the community, and once you’re exposed, you’re exposed.”

“In recent months there have been repeated and massive increases in queerphobic attacks inside the [Mavrovouni] camp,” says Ria. Five people in LGBTIQ+ Solidarity’s group recently reported harassment, while another member was violently attacked because they were outed. “It was always difficult to be a queer person in the camp,” she says, “but right now it is over capacity and the protection possibilities that rarely existed in the past are even more decreased,” she says. Ria notes that “vulnerable” people were once able to make themselves known to officials and could be hosted in a separate area, so, for example, trans women wouldn’t be put in a tent with eight straight guys. Throughout the summer of 2023, the camp population swelled: “there were days with 200 new arrivals on the island,” says Ria, “at times there were over 5000 people in the camp,” she says, adding that max capacity is 3000 people.

In January this year, UNHCR reports that 5531 people live in the camp. Conditions are dire: bitterly cold, overcrowded, overburdened facilities, understaffed, and lengthy food lines. When Roxy waited two hours to receive a box of boiled beans in salty water, she almost cried. “I am very flexible with food, but this is a thing they give to people in jail in Sierra Leone. I looked down at it and thought, why is my life so difficult?” she says. With scarcity and overpopulation in the camp, tensions are heightened, and vulnerable minorities are the first to receive the wrath of people’s frustration.

Roxy lived in the camp for a month before she moved to LGBTIQ+ Solidarity’s Safe House. In that period, she didn’t personally experience any abuse, save an ultimately harmless Sierra Leonean bunkmate who drunkenly slurred about Roxy’s queerness, and a young volunteer who exclaimed, “Oh my god, are you gay?” in a playful, though unconscious attempt at connecting with Roxy. “I am this type of person,” she says, jovially, “I’m very frisky, I’ve been out in Africa, so being out in Europe would be a pleasure for me.”

Lesvos LGBTIQ+ Refugee Solidarity is a significant space of connection and healing for vulnerable minorities at an incredibly vulnerable moment in their lives. As soon as she arrived on the island, Roxy searched “LGBT support Lesvos’ – Ria responded immediately. “When I got to that first meeting, I was so drained; from the camp, the journey, everything,” she says, “it was so good to be able to connect with other group members, all LGBTQ+ from all different countries.” In the stability of the safe house, and under the wing of her newfound international queer community, Roxy continues her work with Trans Alliance Sierra Leone from afar, while it’s likely she’ll step into a coordinator role in Lesvos too.

“Today I’m feeling deep in my heart, in my body, and mentally I’m getting stable,” Roxy says, “this was a tremendous effort from Lesvos Solidarity, and I’m so grateful.”

“The group is very happy to have you,” says Ria. The housemates turn to each other, smiles blooming across both of their faces.

To find out more, donate or support Lesvos LGBTIQ+ Solidarity head here.

Last names are kept private to protect the identities of the interviewees.