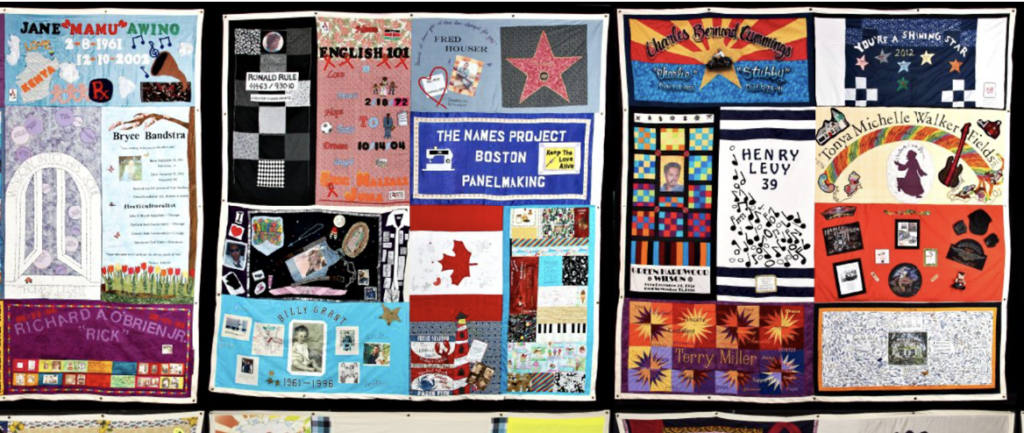

Remembrance and Love: The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, First Displayed Oct. 11, 1987

Today, the tapestry is too large to display all at once, at 54-tons, 50,000 panels and more than 110,000 names.

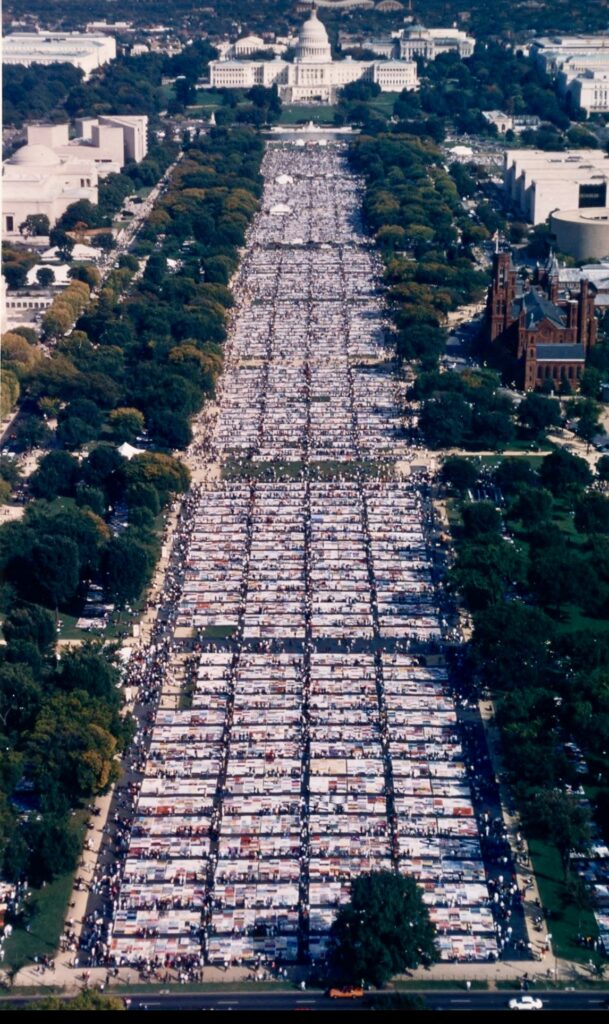

Featured Image: via Facebook, National AIDS Memorial, Oct. 11 1996

By the fall of 1985, most of Cleve Jones’ friends in San Francisco were either dying, or had died. It was five years after the onset of a baffling strange disease. Fear was rampant, as inexplicable symptoms were striking gay men in particular: lesions from Kaposi’s sarcoma, pneumonia and flu-like symptoms, debilitating fatigue and weight loss. Unlike today, there was no treatment for the then-deadly disease that we now know as HIV – the virus that attacks the immune system, which can lead to AIDS.

During those dark days, while witnessing the decimation of his community, Jones happened to be attending the candlelight tribute to the gay activist Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone who were assassinated in 1978. He was struck with an idea:

“I asked people to write the names of their friends and neighbors who had died on placards. We marched to the old federal building and taped those placards to the wall,” Jones tells GO. “And this strange patchwork made me think of a quilt, which brought memories of my grandmother and great grandmother.”

At the root of his concept was the warmth and comfort of a quilt – composed of pieces of cast-offs. “Everybody told me it was the stupidest thing they’d ever heard of,” he says. But eventually others who shared his vision joined in. It was the seedling for what would become the extraordinary NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Jones created the first panel for the AIDS Memorial Quilt in memory of his friend Marvin Feldman. On October 11, 1987, during the National March on Washington, D.C. for Lesbian and Gay Rights, the Quilt was unfolded by 48 volunteers on the National Mall: 1,920 individual panels honoring a precious life lost to HIV/AIDS. Each name was read aloud, and more than half a million people viewed the Quilt.

“The Quilt was created to provide people with a creative form of collective grieving in hopes of helping people to heal,” Jones explains. “It was also created as a weapon to shame the government, and as a tool for the media to understand what was going on behind the mind-numbing statistics.” Jones vividely recalls the Reagan Administration’s slow response to the epidemic. He is grateful for scientific advancements but notes the “terrible irony” that due to current cutbacks to global health programs, “we are now on the precipice of an entire new wave of HIV infections.”

To date, according to UNAIDS, over 44 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the start of the epidemic.

Related: Nepal Turns Out For First Pride Rally Since US Funding Cuts Decimated Services

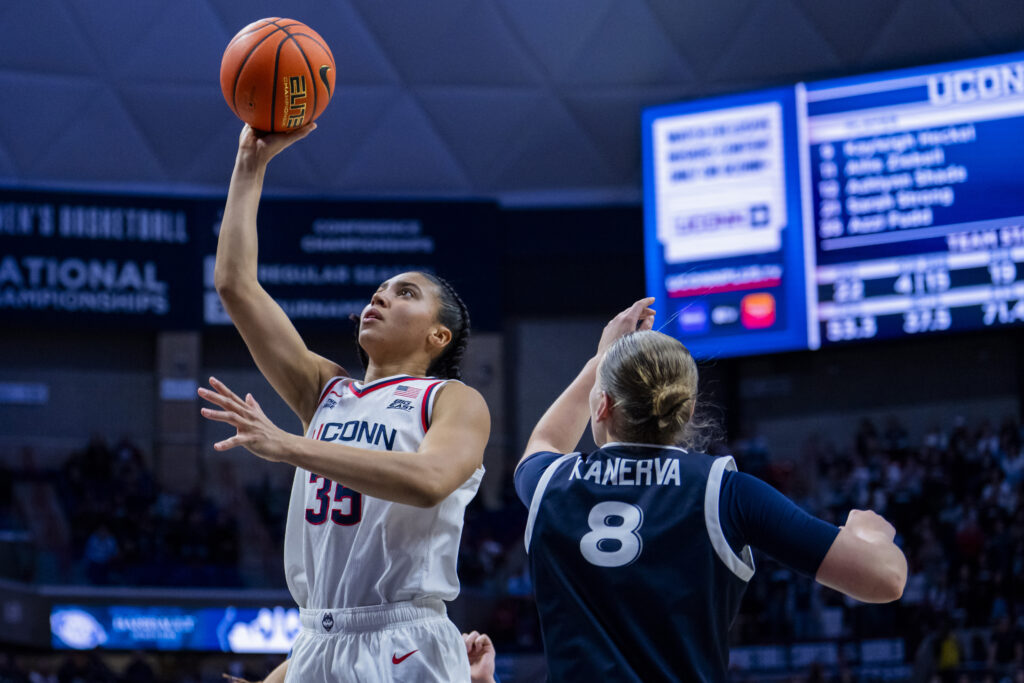

Image via YouTube

After the initial display of the Quilt, its size and and scope of messaging grew. The Quilt toured multiple cities where other tributes were stitched in, each 3 x 6 ft, the average size of a grave. It returned to Washington, D.C. in October of 1988 with 8,288 panels on view in front of the White House.

The last display of the entire AIDS Memorial Quilt was in October of 1996. It covered the entire National Mall, and over 1 million people came to honor the lives woven and painted onto fabric. Atlanta resident, Ronnie Ricketts, 62, was there.

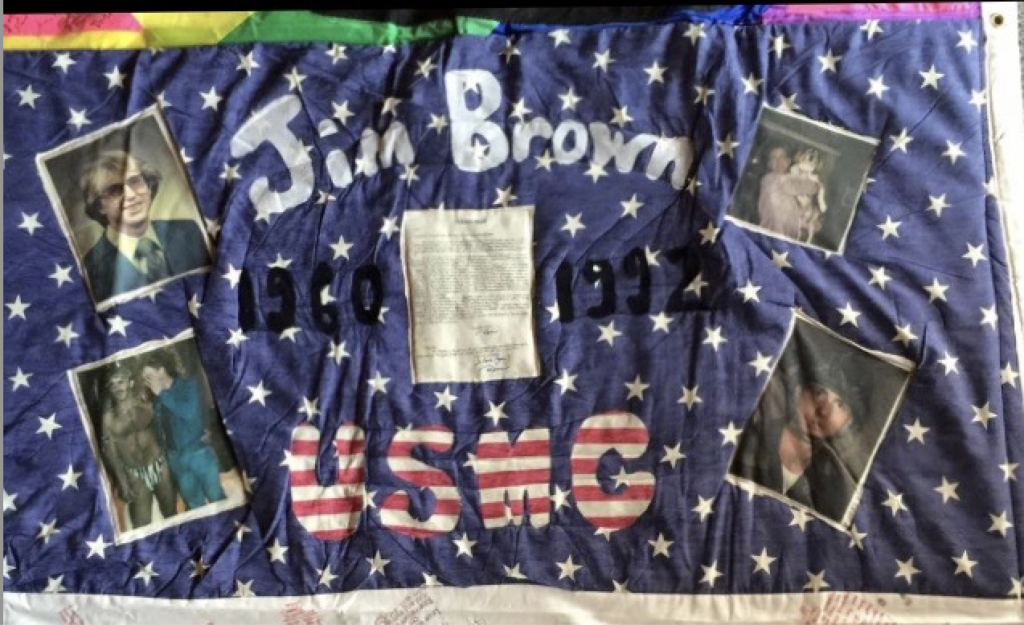

“I have a poster from the event, framed, with two pictures at the bottom of it,” he tells GO, “where I was sitting on the Quilt and reading the letter I wrote to Jim.” Ricketts lost two partners to AIDS, and has been HIV positive himself for 36 years. After losing James McKenzie Brown III in 1992, he says “I drank myself to death for six months.” Then he got sober, and involved with a self-help group that had an assignment: do something you would not normally do overnight.

Ricketts got cloth, padding and iron-on material to make a tribute panel. He wrote a letter to Jim and ironed it on, adding white stars as his partner was a Marine. His friends joined him in D.C. to support.

Image: Memorial panel to James McKenzie Brown III, made by partner Ronnie Ricketts (1996)

At the laying out of the Quilt, he was invited to read the letter aloud to others. “Of course, it was emotional, but it was healing,” he says.

Image: letter from Ronnie Ricketts to the late James McKenzie Brown III, sewn onto Quilt in 1996

What stayed with him? “The love that everybody that was there shared – whether you knew them or not, you knew why you were there, and they knew why they were there, and you just couldn’t help but love everybody.”

Today, The AIDS Memorial Quilt is considered the largest community arts project in history. Each year, National AIDS Memorial, stewards of the Quilt, orchestrates over 1,000 displays across the country and manages the interactive, searchable online Quilt. The patchwork is too large to be displayed all at once, at 54-tons and with 50,000 panels with more than 110,000 names – each, an enduring memorial stitched with love and remembrance, and the wish to say to the world: this life mattered, you were loved, you were missed.

Image: one of 50,000 panels of The Quilt, via National AIDS Memorial