Reflections From The Front Lines: Stories Of Survival And Resistance From Two Veterans Of The Stonewall Uprising

June 28 marks the 56th anniversary of The Stonewall Uprising. GO spoke with two veterans of the uprising to commemorate this day.

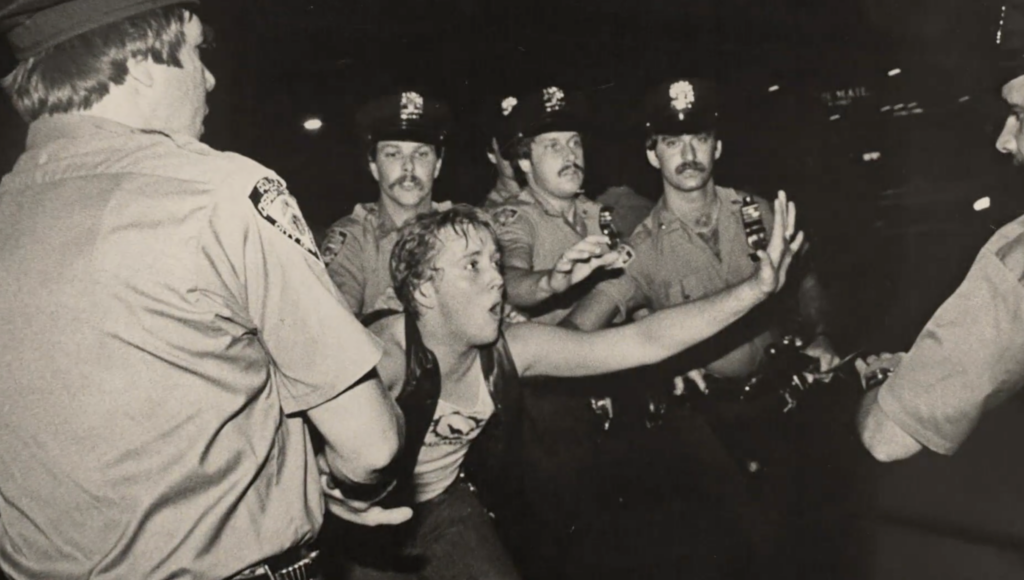

Featured image: Police clash with a protester at Stonewall in 1969. Photo by Bettye Lane via First Run Features.

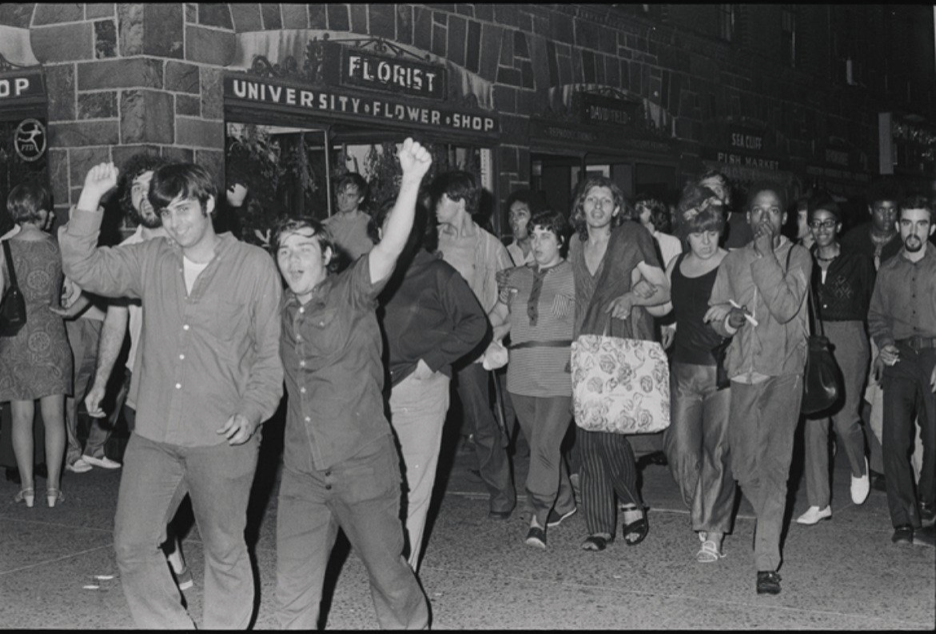

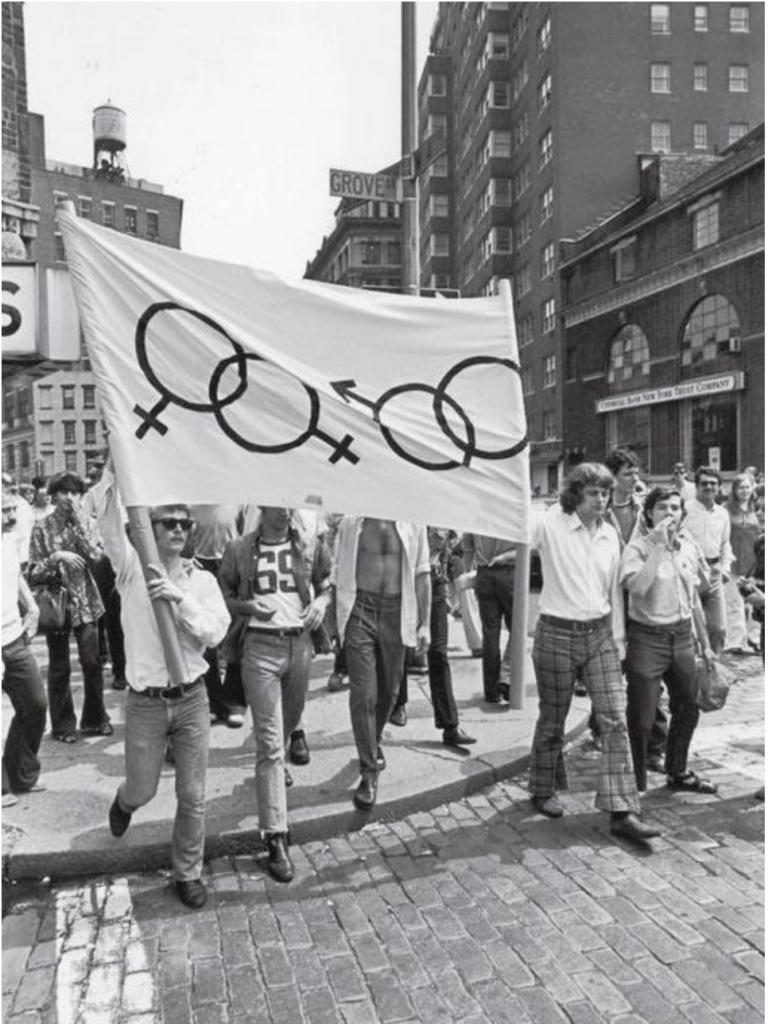

It’s one of queer history’s biggest milestones and the spark that galvanized a movement: June 28, 1969, the first night of the Stonewall Uprising. NYC police raided The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in The Village, one of the few safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community at the time. Patrons responded with a resounding “hell no” when police began pushing and beating customers inside. Protests and violence ensued in the days that followed, growing in intensity and culminating in historic gatherings that would be the precursors to New York City’s first Pride Parade one year later.

June will always be our month, and 56 years later, that rebellion is still regarded as the launch pad for the LGBTQ+ rights movement. GO joins you in commemorating that pivotal moment, as we remind ourselves that no matter how oppressive the climate, we will never go back, and we will not hide.

Victoria Cruz

A drag queen checks on her cheating boyfriend when all hell breaks loose

Video from The National Park Service’s Stonewall Oral History Project,

in partnership with The LGBT Community Center and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Original sign from the Stonewall Inn.

It was close to midnight on June 28, 1969 when Latina trans activist Victoria Cruz, now 78, arrived at The Stonewall Inn. Raids weren’t uncommon at the bar. After a pay-off with cash in a bag, the police usually left. “They used to come in and raid the place, and the house would put the lights on as a signal. If you were two men together, you’d look for a lesbian to sit or talk to,” says Cruz, who was 23 at the time. “And if the queens had makeup on, they’d make you take it off with the dirty mop water from the bucket that they used to wash the floor.”

That night felt very eerie, hot, and humid as she remembers. The moon was full. “Judy Garland had just been buried, and people were down – it was like her little bluebirds were depressed. The Village was very solemn. It was like the calm before the storm,” she tells GO.

For the “Friends of Dorothy” (code for gay at the time), the loss of Judy Garland may have added fuel to the flame, but the fire had been raging for years. Back then, gays were deemed deviant, and homosexual acts were illegal in all states but Illinois. Some queers lost their minds to forced lobotomies, or a skull to a club wielded by the cops. “Masquerade laws” targeted drag queens, requiring them to wear three articles of clothing deemed appropriate to their designated gender.

When the paddy wagons came that night—not an uncommon happening at downtown gay bars—Cruz was hanging out on the streets with her friends, like drag queen Sylvia Rivera. She was scheduled to work early next morning at the beauty parlor, but was suspicious of her boyfriend Frankie, a Stonewall bouncer. She decided to check in on him. “He was a cheat.”

Victoria Cruz and her then-boyfriend, Stonewall bouncer Frankie. Spring 1969. Photo Courtesy of Victoria Cruz.

“The cops went inside. Then the crowd started getting a bit rowdy outside, and they started throwing pennies at the cops, calling them names, like dirty copper – all kinds of names, pigs and camarones—Spanish for shrimps—because most of them were Irish, and when they drank, they turned a little pinkish,” says Cruz. She recalls how people were brought to the paddy wagons outside, and how the queers started moving toward those who had been apprehended.

“When they saw that one queen got punched, a brick came out of the shadows and cracked a window,” Cruz recalls to GO.

There was no turning back.

Years of hostility toward gay people had erupted, bolstered by other uprisings taking place across the country, during that turbulent time in the ‘60s. It was “the riot that built a community,” according to fellow Stonewall veteran and author Mark Segal, PhD, and Curator of The Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center.

“You got to remember, this is the height of the Cultural Revolution in America,” Segal tells GO. “Blacks are fighting for their rights, women are fighting for their rights. Latinos are fighting for their rights. And I said, ‘What about us?’”

Mark Segal

The Boy Next Door, who followed the gay migrant wave to NYC.

Mark Segal (R) with Jerry Hoose (L) in the foreground of the photo. Sylvia Rivera in the background. June 1969.

Photo Courtesy of Mark Segal.

“We were people who were invisible,” says Segal, who moved to NYC at 18 from Philadelphia, where he thought he was the only gay person in a city of almost two million people.

“I knew for some odd reason I couldn’t talk to my parents. I knew I couldn’t talk to my friends, and one day I went to the library and discovered, gee! The word that I am is ‘homosexual.'” The literature directed him to look up religion, immorality, psychiatry, and criminology.

“And I didn’t feel like that. It was obviously very depressing,” he says. “So I decided when I graduated high school, I would move to New York, where I thought there were other people like me.”

The self-described boy next door arrived on May 10, 1969. He’ll never lose the memory of that first brilliant night when he went down to the Village. “Nirvana. I found Christopher Street, which in those days was the major neighborhood. I mean, we were invisible.”

“You have to realize that it was illegal for us to be appear on TV or radio,” the Founder of the Philadelphia Gay News tells GO. “There was an FCC regulation about having immoral people on TV. Therefore, I had no role models. There was no one for me to ask: Why am I the way I am? Will I find happiness in my later life? Will I be able to get married? So for me, the answer was, let’s go to New York and find more people like me.”

As a young person, he immediately made friends around Christopher Street, which was THE place to hang out. At the end of the night, the guys always went to Stonewall.

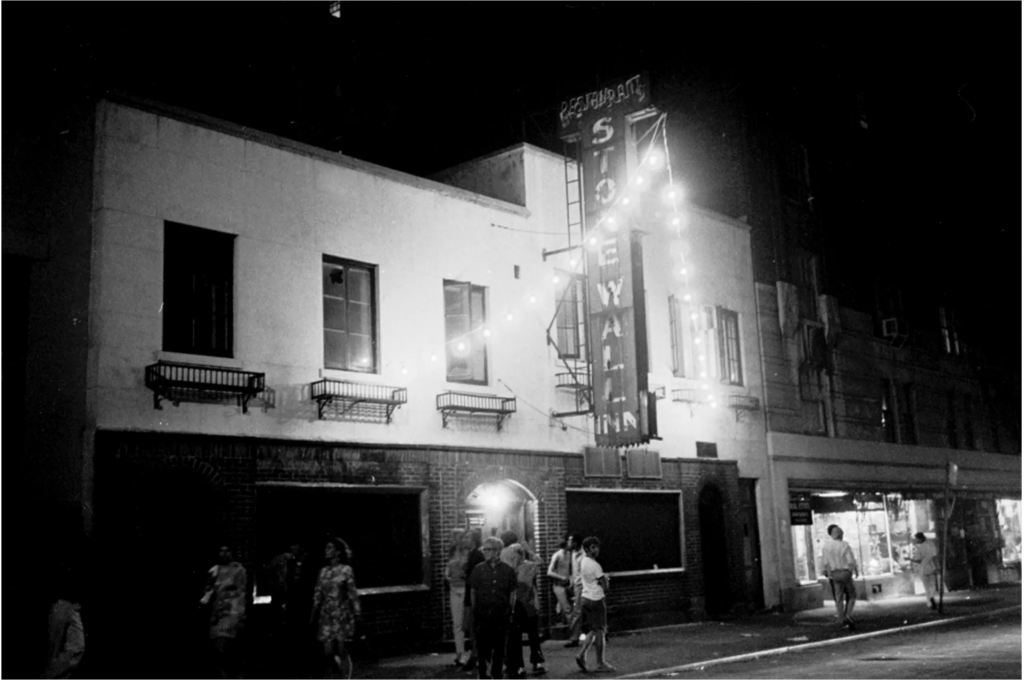

“It was the only place in the entire city where people like me could dance, hold hands, kiss someone that I loved or liked or wanted to date,” says Segal, now 74. “Even though it was an illegal club—it was dirty and sold watered-down drinks—it was a safe place for us to dance. It was a safe place for us to meet, until that night.”

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Manhattan, 1969. Photo by Larry Morris/The New York Times.

Segal didn’t see the cops take the usual payout. Something was different. They burst through the door. “They started busting up the bar. They started throwing people up against the wall. They took bottles of liquor and threw them against the wall or towards people. People were intimidated in every way, shape, and form. I had never seen such violence in my life before.”

Everyone in the bar was stunned and shocked, from the young men like him who made up the majority, to the women (typically butch) and drag queens, who, along with People of Color, were allowed in smaller numbers that the bar owners deemed best for business, according to Segal.

In fact, there were more trans people outside at the riots than you would expect, he says. The reason: “Those people with jobs, good jobs, and family in the area, the minute they got outside, they ran. More marginalized people – the street kids, the homeless – we were all the ones who stayed.”

Segal was trapped inside. Scared to death. Until they finally let him out. One cop went to an older guy and demanded money, Segal recalls. Eventually, all were released while workers and cops stayed inside. He estimates about 50 people outside that first night; some who were there recall hundreds.

“Most people cannot think of what it felt like to be LGBT back then,” Segal reflects. “But you got to remember—we were not only invisible, the entire society disapproved of us to the point where the police could do what they did inside Stonewall. Therefore, most people – 99.9% of our community – were in the closet, and most people just ran when they got outside. They didn’t want their name in any newspaper. They didn’t want their name in any file in the police department. They just ran, and those of us who stayed didn’t have much to lose.”

Despite the mayhem and bloodshed, Segal says that night was one of the best things that ever happened to him. Marty Robinson, an LGBTQ pioneer whom Segal regards as an unsung hero in our community, gave him some chalk and said, ”Go up and down Christopher Street and write ‘Tomorrow’s Night Stonewall.'”

“And that’s what I did,” says Segal, “I didn’t realize I’d become an activist, but I did, and I think within the next few hours or the next night, I said, ‘This is what I’m going to do the rest of my life.’

“I think there were a lot of people who thought about coming back the next night and continuing the battle, in a sense. I think at that point, we were radicalized and decided it was time to fight back.”

Within 30 days, more than 500 people marched from Washington Square to Stonewall to commemorate the riot’s one-month anniversary, organized by the newly formed GLF.

Mark Segal, far right, marching with the Gay Liberation Front during the first post-Stonewall March in July 1969.

Photo courtesy of Mark Segal.

“Gay Liberation Front would be the organization that came from the ashes of Stonewall and took that spirit forward,” Segal proudly says.

One year later, thousands came together for New York City’s first-ever Pride March, exceeding organizers’ expectations. Fast forward to Pride Month 2025, with a whole lot of love and rebellion along the way. June will always be sacred to our community, and the Stonewall Uprising, revered as a catalyst that advanced the civil rights movement in the U.S., and LGBTQ+ rights across the globe.