Pastrami Tacos, 7-Eleven Passover Seders, & Baby Strollers In Tompkins Square Park– Fuhgeddaboudit!

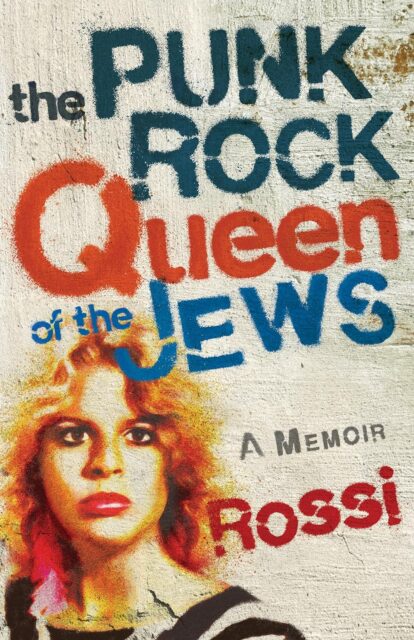

In “The Punk Rock Queen of the Jews,” Rossi explores her eccentric childhood, her time as a runaway teenager, and her devotion to 1980s NYC.

NYC chef, radio host, painter, acclaimed playwright, queer Hungarian Jewish feminist: Rossi is a true multihyphenate (in fact, she was one of GO’s 2016 Women We Love). “Published author” has been part of Rossi’s skill set since her first memoir, The Raging Skillet, was published by Feminist Press to wildly enthusiastic reviews. In her follow-up, The Punk Rock Queen of the Jews, Rossi explores her eccentric childhood (including a mother who communed with the dead and held Passover Seders in a 7-11 parking lot), her time as an ex-runaway teenager trapped into submission by a Brooklyn “cult-busting” rabbi, and her devotion to 1980s New York City that led her back to her faith. GO spoke with the punk rocker about surviving a misspent youth, NYC then and now, and the power of telling your story.

GO Magazine: You have spoken a lot about your unusual childhood, calling it “half trailer park trash and half Orthodox Jewish, with an eccentric, mentally questionable Yiddish mama.” Tell me more about that childhood and how it’s shaped you as an adult.

Rossi: As a kid, you think that everyone’s parents are like your parents. I was about seven years old when I realized that other kids’ mothers didn’t sit at the kitchen table talking to dead relatives and that ketchup actually came in a bottle, not a pile of a hundred tiny packets stolen from Burger King. My mother was an over-the-top, 300-pound Yiddish mama, who managed to meld her Hungarian Orthodox Judaism with practicality. So, when my folks bought a crappy piece of land in the Florida Panhandle, it put us on the path to be the only family you will ever meet who had kishka and grits for supper. Don’t even get me started on having Passover Seders in the parking lot of a 7-11. Fuhgeddaboudit. Having such a kooky absurd childhood actually set me up perfectly to be a caterer in New York City. I am famous for my wacky fusions. Jerk chicken on latkes anyone? How about pastrami tacos with half sour pickle confetti?

GO: You ran away at 16, only for your parents to put you with a “cult-buster” Chasidic rabbi known for reforming “wayward Jewish girls” in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn. While there, you endured not only boredom, but violence and abuse. Can you tell me more about this time in your life?

R: It took me a long time to really write about it. I wrote about it gingerly and got into it in a few chapters in my first memoir The Raging Skillet, but I always kept it, let’s say, G-rated. I don’t think I could have really written what happened there while my parents were alive, because it would have killed them.

They thought they were shipping off their wild child to be among safe religious people. They didn’t realize they were sending me into worse danger than I’d ever experienced before or since. A lot of the kinds of things a teenage girl might have nightmares about came true for me on Kingston Avenue. It wasn’t until I started writing about it in a deeper, more honest way that I started to feel sorry for that teenage girl. I was like, “Holy hell. That poor thing. Wait a minute. That poor thing is me!”

GO: There has been a lot of media lately about the “troubled teen” industry, and how young people have been kidnapped and put in dangerous situations–by their own parents. Are you familiar with these narratives, and if so, how are they similar to/different from your experience?

R: My parents dropped me off with Chasids and left me there, but I suppose I could have left. I didn’t have any money or anywhere to go and didn’t have options, but it wasn’t like I was locked in a cell. I was scared out of leaving by being told I’d be sent to reform school if I left. Even if I did run away, NYC was so dangerous in 1981. Not a great time to be a homeless teenage girl with no money. I know now that what they were really trying to do was pray the gay out of me. Took me a while to figure that out.

GO: Can you talk a bit about how you finally broke free of the toxic culture you were embedded in, and what obstacles lay ahead?

R: I woke one morning and decided that I was living a lie. I was letting the Chasids think they might bring me around to be one of them in exchange for food, a warm bed, a safe place to stay, but it was not me. I decided to throw out my maxi skirt and put on ripped jeans and a Blondie T-shirt, damn the consequences. The free dinners dried up very quickly after that.

GO: What made you decide to tell your story, and why now?

R: After being very distant for most of my life, in the last five years of his life, my father needed my help. He had no one else he could trust. It was ironic that all those years later, he turned to his black sheep. Some of my old friends asked me how I could jump in and care for my dad, who had mostly abandoned me when I needed him, and I said it was a way of going back in time and saving myself, too.

Caring for my father in the last five years of his life was the greatest honor of my life. In the last few months, when he was in hospice care, I rented a hotel room near where he was in LA. I couldn’t sleep at night, so I started writing, and out came 300 pages in an avalanche of pent-up stuff I’d been carrying around for many years. It uncorked me. I didn’t want to tell the Crown Heights story. It was too painful. But now it was demanding to be heard.

GO: What advice do you have for young people who are facing similar challenges and pressures to be someone they’re not?

R: Living a life that is not who you really are, is like killing yourself bit by bit every day. My heart breaks in a thousand places for our youth who have taken their own lives due to being bullied, isolated, misunderstood, cast out. But you can take your own life and remain alive, too, by throwing away who you really are, just to be left alone, just to not be abused, just to fit in, just to not be shunned. But in the end, what’s left of you would just be a shadow of your true glorious self. Not a lot of glory in the shadows. I say, rise up, rise up and live!

GO: How do you balance your Jewish faith with your queer identity?

R: For a long time, it felt like I had to leave Judaism to be happy and gay. But then I found CBST, Congregation Beth Simchat Torah, the world’s largest gay synagogue. The first time I walked into services I watched a spunky, young female rabbi, Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, give a heart-wrenching, powerful, speech! A woman rabbi?! That alone made me celebrate, but that she was a lesbian, too! Oh my god! I knew I’d found home.

I feel deeply Jewish. It’s in my bones, in my soul, in my kishkas. But I know that in the end, if there is anyone up there or out there who is judging us, it’s not about did we keep kosher, or did we light candles on Shabbos. It’s about did we share love? Were we kind? Did we open our hearts to others? Did we live our lives openly and honestly?

GO: You are also “Chef” Rossi! Tell me about your relationship with food and how it evolved into a career path.

R: At a bar I was working at called Trivial on 21st in Manhattan, the kitchen would close, and my regulars never wanted to leave, so I started going into the back to invent things for them to eat. I’d cook up things like Buffalo chicken nachos–they were a huge hit. All the kooky dishes of my childhood really opened me up to avant-garde cooking. I constantly invent and have fun with new dishes. Or take a new spin. It never gets boring. Two nights ago, I fused Indian and Mexican and made Lamb Vindaloo tacos with pineapple ginger salsa.

The ’80s were a terrible time for female chefs. No one wanted to give me a break. They all wanted to sexually harass, degrade and abuse me. But I’d gotten so tough from surviving Crown Heights, that I gave it right back to them– Don’t mess with this lady!

GO: You are a lifelong New Yorker, and you have witnessed the city endure its own hardships–the AIDS crisis, 9/11, racial unrest–as you were enduring your own. What keeps you in NYC?

R: I used to think of NYC as heroin. It made you sick at first. Many didn’t survive it, but then after you got through the first few years, you were hooked. I don’t think of NYC like that anymore. Now, I think of it as my baby. Well, I think of 1980s NYC as my baby. Sadly, it’s disappearing more every day. The Second Avenue Deli is a Chase now. Feels like a crime against humanity. There are baby strollers in Tompkins Square Park instead of punk-rockers. The piers off Christopher Street where I used to sunbathe topless surrounded by gay boys are filled with tourists and jogging yuppies. It makes me sad every time they tear down a beautiful pre-war building and put up another boring glass skyscraper. But there are still jewels that warm my soul: long walks along the East River (if they ever finish the construction), latkes and applesauce at Veselkas, margaritas with my gal pals at the Cowgirl Hall of Fame where I had my 29th birthday more years ago than I care to count…and got one of the best kisses of my life at the payphone. Back when we had payphones.

GO: The Punk Rock Queen of the Jews is your second memoir. You’ve been published in many outlets including The New York Post and McSweeney’s, you have a wildly successful radio show, and you’ve written plays and even a one-woman show! What first led you to writing, how do you choose what to write, and what keeps you writing?

R: I’ve been told that I should be more structured and write every day, no matter what. But I don’t write like that. It’s more like my inner writer-creature forces me to the pen. There’s a voice somewhere deep inside me, it’s usually funny, often laced with melancholy, demanding to be let out. I love to write during rainstorms, when I’m sick, when I’m sad, when I’m lonely. I very rarely feel like writing when I’m happy. Some might say, that’s not a good thing, I don’t know. Isn’t happy writing terribly boring?

GO: Any advice for those who want to write a memoir? Do’s, don’ts, general encouragement?

R: It took me 14 years to get my first memoir published. Fourteen years and 30 rewrites and almost a hundred rejections. I kept pushing because my story was burning inside me demanding to be let out

A good memoir is revealing, humiliating, makes you feel exposed, embarrassed, open to painful rejection and more. The writing of it forces you to open yourself up and look deeply at things in your life you may not want to dwell on. If you do dwell on them, you may not want to really tell the truth, to really make yourself possibly look like a jerk or a bad guy. But you must tell the truth! Or don’t do it.

You are putting your life out there for the world to see. You want to ask yourself, “Do I HAVE to do this?” If your answer is yes, proceed. Onward!!! If your answer is “No, but it might be fun,” play bingo instead.

GO: Anything else you’d like to add?

R: People in my life know that I’ve had a spectacular amount of loss in the last few years. I lost Suzy, one of my dearest friends since I was 11 years old to esophageal cancer, then a few months later my sister died unexpectedly and shockingly the day before Gay Pride. The following year, my baby brother was found dead on Halloween night. All of them, only in their 50s.

I painted Suzy’s portrait, and she’s smiling at me as I write this. I wrote a full length play about my wild and zany sister called Ms. New Jersey. I painted my brother’s portrait, and he lords over my living room now, much as he always wanted to. My first memoir was a way to honor my mother. She lives on in the book and the play. My work gives life to my father, sister, brother, and Suzy. I feel blessed to have found a way to keep them in my life forever and to share them with you.

Being a writer saved my life. Now, I pray that it will save other people. That young gay boys and girls will read my book and know they are not alone. They just need to hang on a little longer. It will get gorgeously, beautifully, amazingly better.

The Punk Rock Queen of the Jews is out now.