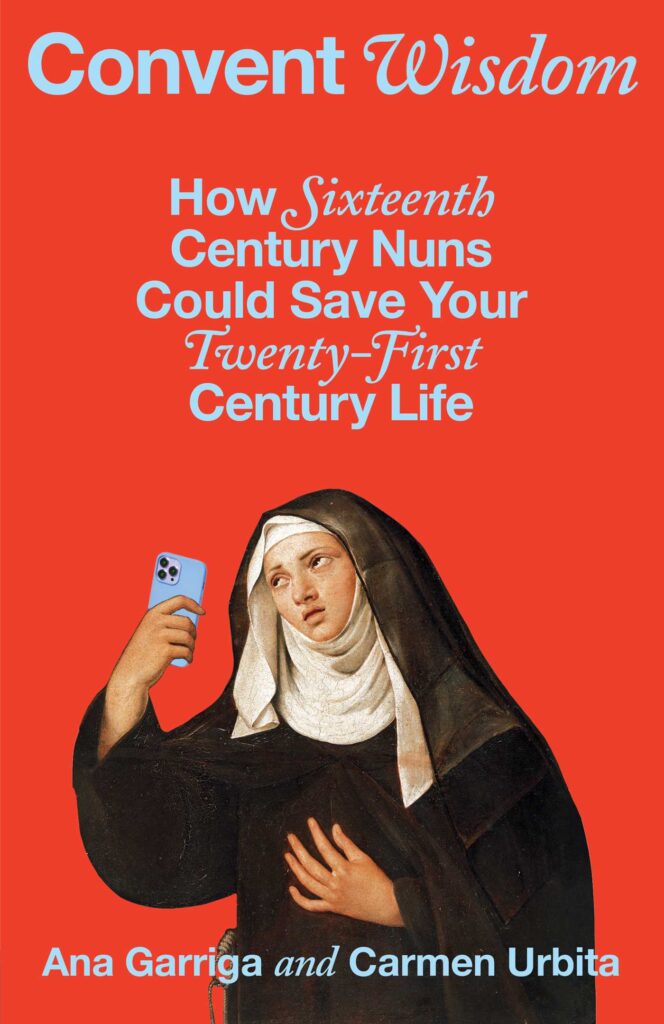

Your New Self-Help Guide: “Convent Wisdom: How Sixteenth-Century Nuns Could Save Your Twenty-First-Century Life”

Plagued by doom-scrolling? A lesbian situationship? A new book by two queer Brown PhDs offers monastic anecdotes to help with your modern conundrums.

Featured image: courtesy of Simon & Schuster/Avid Reader

Money troubles? Nuns who mass-produced liturgical manuscripts for cash have tips. Perplexed by a lesbian situationship? The poetic longings of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz might inspire. Can’t keep your focus? Mary of Jesus of Ágreda reportedly had the miraculous ability to be in two places at once. Convent Wisdom: How Sixteenth-Century Nuns Could Save Your Twenty-First-Century Life is a deliciously smart and funny self-help book that takes you into the secret lives of Baroque nuns.

This gem was penned by Ana Garriga and Carmen Urbita, two queer Brown University PhDs who all but took vows of poverty signing on to a life of graduate studies. Their collaboration got off the ground after they discovered a shared love of nuns and started a Baroque nun podcast during Covid. As is clear from the book, they embrace the sisters as much more than cloistered dependents; rather, relatable women as capable of a jealous fight as any modern day woman battling over make-up. Garriga and Urbita see convents as cells of resistance, and spaces where non-marriage-minded 16th- and 17th-century women could lead multi-dimensional lives and find their identities; families could avoid the cost of dowries that were going through the roof, and what’s not to love about communal living and wearing a Benedictine habit?

“I was then thirteen or fourteen years old, she was in the house, on that occasion…now, Sister, I wish another tongue than my own to tell of the transformation wrought in us all by her holy conversation and her practice of prayer and mortification.” It’s the friend crush we can all relate to – the first rapturous time María de San José saw Teresa, future saint and founder of the Discalced Carmelites. As documented in Maria’s 1585 Book of Recreations, Maria wasn’t beyond hurting her knees to get a good peek through the keyhole to Teresa’s room. She was one of many bedazzled teens who swarmed around Teresa, peering through tapestries to hear her prayer exercises and glimpse the spectacle of self-flagellations by someone “who at her earthly core, was a frail woman pushing fifty.”

Authors, Ana Garriga and Carmen Urbita

Convent Wisdom is structured with chapters on girlfriends, body, love, money, soul, fame and work (see sub-heading, “How to Say No to Your Boss With the Intricate Yet Unyielding Rhetoric of a Nun Putting Her Confessor in His Place).” For anyone who has felt the tedium of long work weeks, having ‘working remotely’ canceled by the new boss, or the indignities of being crammed in the subway: take heart from Maria who documented being ordered “to write over again everything that was written in those ten notebooks. I feel the greatest repugnance at doing this work again.” Like the authors who took to whispering “greatest repugnance” like a prayer when they sensed the end of another soul-crushing day, you too, might find solace in repeating this litany.

The section on Body opens with, “Nothing Tastes as Good as Holiness Feels: How to Turn Food Neurosis into a Regectory of One’s Own.” Let’s just say modern intermittent fasting is nothing compared to the deprivations sustained by many a Poor Clare. Some of the regimes made watery bean stew and a single egg look like Michelin-starred dining. If you’ve gotten in the pattern of starting the day with a shot of tumeric and ginger, or cultivating your own symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast, as the authors point out, the judgments faced by nuns “bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the looks of disgust that contemporary diets can provoke.”

Take Veronica, for instance (she “subjected her body to far more severe practices than the consumption of proteins of dubious origin”). For five years she lived on bread and water. Except on Fridays, when she allowed herself to eat exactly five mandarins, one for each of Christ’s wounds. Her superiors, alarmed, confined her to the convent infirmary trying to get her to eat at least a few spoonfuls of soup. Yep, women’s eating habits have always been scrutinized, and there was no shortage of folks who dared question whether Veronica’s fasting was genuine.

Those with heartier appetites might enjoy the section, “A Multitude of Freshly Baked Loaves and Rolls” – How the Mystical Visions of a Franciscan Nun Explain Your Obsession with Recipe Videos.”

Related: Convent Drop-Out Kelli Dunham Is Drop-Dead Funny

Seventeenth Century Catholicism had its perks, and offered ample opportunity to set oneself apart from the pack. Sister Juana de la Cruz, for instance, spared no effort distinguishing herself in the crowded race for the fame of sainthood. “She fasted for up to three days straight, levitated at the most inopportune moments, and experienced elaborate visions, which, in the throes of ecstatic alienation, she insisted on describing to her fellow sisters so they could hastily copy them down,” Garriga and Urbita write.

If you’re going through it, probably a nun has gone through it. There’s nothing new under the sun, not even trends like Taylor Swift–inspired friendship bracelets which it seems had a precursor in 16th-century demand for traded devotional items, specifically Saint Juana’s blessed beads.