United Must We Stand: Unpacking Anti-Blackness Within Queer Community Activism

With so much energy surrounding activism following November’s unfortunate election results, thousands of people—including the queer community—have begun to rally in political realms.

With so much energy surrounding activism following November’s unfortunate election results, thousands of people—including the queer community—have begun to rally in political realms. While it’s heartening to feel the energy of so many individuals fighting for social justice-based issues, it’s more important than ever that we begin to unpack the ways that oppression persists within marginalized communities.

A critical response to the Women’s March policies and practices came from the lack of intersectionality. Complaints were made about origins in appropriating and erasing The Million Woman March (a 1997 Philadelphia-based march organized and created by Black women to bring light to issues of injustice that they face), followed by the allowance of Black and other women of color into positions of power within the organization’s planning committee. That the latter only came after vocal criticism on a large scale illustrates how intersectionality isn’t as integral to mainstream feminism as the movement had hoped.

The only recently rising popularity of intersectionality as theory amongst mainstream feminists is concerning because it’s one of the ways that we begin to see a hierarchy of power unfold. As a term, “intersectionality” didn’t exist until it was created by Kimberle Crenshaw, a Black female scholar and civil rights advocate, in 1989. Its meaning has been expanded upon throughout the years by other Black women, but it’s clear that the term itself plays a critical part in understanding social justice and feminist practices. Today, we see that credit largely erased, as many self-identified feminists will begin to “adapt” intersectionality without truly understanding its roots or role within Black feminist theology.

Why is this important? Because in many social justice movements, the foundations of these frameworks—especially within queer ac-tivism—were built on the backs of Black people. To have that work go uncredited and unconnected to Black history is both a disservice and a complacency in anti-Black violence routinely practiced in our society.

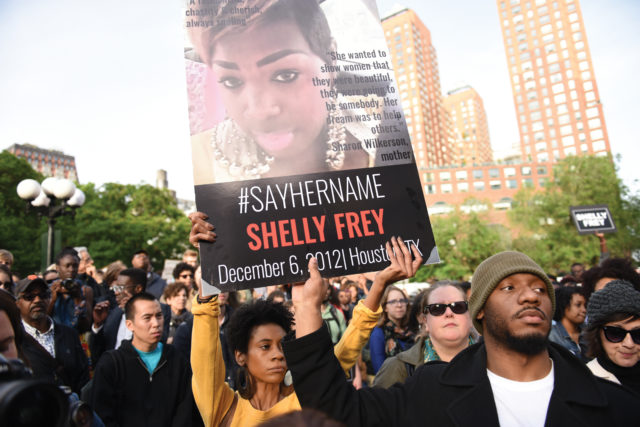

There’s no doubt that Black activism has played a role in almost every other form of mainstream social justice movements. Events crucial to the framework of queer activism it-self—the Stonewall demonstrations, Black Lives Matter—were all significantly formed by the work Black and trans women have achieved. And yet, we still see the queer community often complacent in erasing Black people from its history of activism and triumph by undermining the leadership of Black people involved. When we disconnect Marsha P. Johnson’s work and activism from the significance of the Stonewall demonstrations (along with her other contributions that she has offered though her bravery to live life as she was meant to), and erase the queerness of two of the Black Lives Matters’ organizers—or use their queerness to exist in opposition to their Blackness—anti-Black violence could and has sprung forth as a result.

The LGBTQ community must begin to do the work of unlearning these violent structures and recenter the roles of Black leaders into our communities, and to queer history and queer activism at large. We must begin to unravel the ways that anti-Blackness remains embedded within the structure of many queer activist movements: Do we make sure to include the contributions of Black labor when we think about queer activism today? How do we begin to decentralize whiteness as the default of the queer experience and allow for Blackness to exist in various queer circles? And, especially, how do we celebrate the lives of Black individuals in our community, no matter how much they “pass” or conform to our ideas of what queerness should look like?

Whether we want to admit it or not, the queer community can be complicit in the same violence and oppression that leaves Black and other people of color feeling like strangers in our own communities. It’s far time that we begin to examine the ways that we are complicit in anti-Black violence and begin to break down the structures that keep a hierarchy of white supremacy within the LGBTQ community.

This Black History Month and beyond, spend time learning about Black queer heroes. Marsha P. Johnson, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Bruce Nugent, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Kye Allums and Janet Mock are just a few of the more well-known Black queer individuals who have been brave enough to live their truth and use their voices to fight injustice. But there are others within the queer community—those who are not household names—who are also doing their part to bring awareness to what it means to be Black within the queer community (and queer within the Black community) that should also be recognized and celebrated. Black History Month is often used as a time for reflection on contributions that Black individuals have made in the past, present or future, but it’s also a call for action.

Cameron Glover is a journalist and an editorial fellow at Tech.Co.