The Isle Of Lesbos Is The Lesbian Paradise Of Your Sapphic Dreams

Lesbos freed me from my shame.

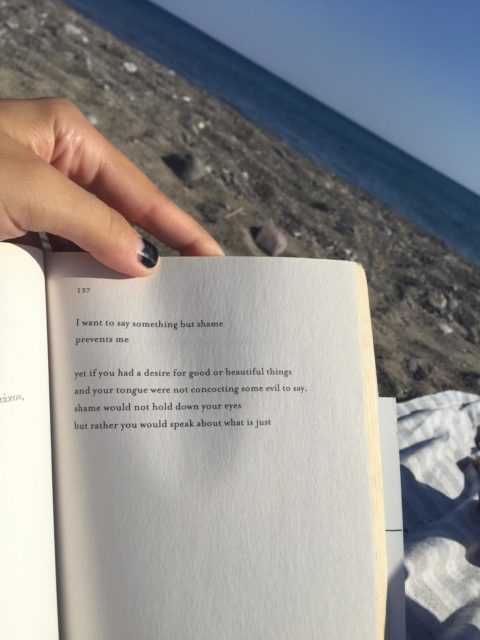

I want to say something but shame

prevents me

yet if you had a desire for good or beautiful things

and your tongue were not concocting some evil to say,

shame would not hold down your eyes

but rather you would speak about what is just

— “If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho” – translation by Anne Carson

I sit at a waterfront Greek taverna, listening to the waves of the Aegean lapping the sand below. The smells of rosemary, thyme, olive trees and the sea wash over me. I half-listen to the trivia night at the bar next door as I scan its patrons: they’re mostly lesbians, which both surprises and comforts me. It’s not every day that I’m in a space filled with gay women and that old feeling of shame nags at me: Is it okay that we’re being so openly gay? Is that man with his kids at the next table going to angrily get in the faces of the lesbian couple walking by? I wait, but nothing happens and instead, the winning trivia team gets their prize: a dildo. Surely this will ignite a disparaging comment by a straight person, but all I hear are cheers for the winners. I feel my shame getting replaced by a new, lesser-known feeling: safety.

This was my first night in the tiny beachside village of Skala Eressos on the Greek island of Lesbos. Skala Eressos is the birthplace of Sappho, the lesbian poet famous for her love of women and poetry so powerful that Plato called her the “Tenth Muse.” The island also birthed the term “lesbian” as the word, which describes anything native to Lesbos (yes, all gifts and cats from Lesbos are Lesbian), became so associated with sapphic love that its original meaning became secondary. Well, secondary to everyone except for Lesbians from Lesbos, some of whom sought to reclaim the term and ban the Homosexual and Lesbian Community of Greece from using the word “lesbian” in their name. Sorry, Greek Lesbians, the gays are keeping this one.

The native Lesbians of Skala Eressos seem fine with the gays’ takeover of the word, however, as queer women stimulate the local economy. In fact, signs of Sappho are all over the village: Sappho Cine, Sappho Travel, and Sappho Real Estate. It’s a surreal sight. In what world is not only a poet exalted to such a degree but a lesbian poet at that?

My dreams of a Mamma Mia-inspired lesbian commune finally feel attainable here, so I stop by Sappho Real Estate to speak with Ioanna, the owner, who also owns Sappho Travel and runs the International Eressos Women’s Festival. I ask Ioanna how the locals feel about Skala Eressos being a lesbian destination. She Greek shrugs like a real-life shrug emoji. It doesn’t bother anyone. Queer women bring in money and are respectful of the village, so who cares? Skala Eressos thrives on this symbiotic relationship between lesbian tourists and straight Lesbian locals, and there’s an acceptance of gays here that I’ve never experienced anywhere else.

I grew up in New York and live in LA, both of which offer infinite spaces for straight people or people like me who think they’re straight until they’re 22 years old. While heteronormative spaces everywhere are never-ending and diverse, the LGBTQ community is not so lucky. The spaces available for us are limited and even more so for women and trans people, who all remain less visible than cis men in our community. And these spaces are predominately bar-centric.

When I was closeted, I used alcohol to manage the shame of feeling different—and when I came out, I kept drinking to celebrate my new party-friendly community while trying to forget all my shame. I kept drinking until I drank half a handle of vodka, crashed my car and found myself alone in a jail cell, enveloped in the shame of knowing that this was the culmination of a lifetime of self-loathing. I was 28 when I stopped drinking and suddenly found myself without any spaces at all. I felt invisible as a sober gay woman in gay bars filled mostly with men, and over time, the idea of a non-party space for queer women became less real. I didn’t even know what it would look like.

Now I understand what this space can look like, as I sit on the nude beach of Skala Eressos skipping rocks. The public beach is to my left but the fully clothed men, women, and children there don’t care much about the naked women just a few meters away. I care, though. I’ve spent every day on this nude beach filled with queer women and am still moved by the visibility of openly gay women hanging out so publicly, so nakedly.

A friend is with me today, and I ask if she’ll photograph my book of Sappho between my legs. I want to birth Sappho in her birthplace in the way that I feel like she birthed me. After all, where would I, a half-Greek lesbian writer, be without Sappho? I position the book between my legs as the sun beats down on my own naked body and I feel the shadows of my old gay shame disappear with the light of something else: my gay pride, as I feel a connection to a lineage of powerful queer women that stretches from Sappho and those who came before to all of us after, to me and the women here on this beach, and all of those seen and unseen within our community.

Before I leave Skala Eressos, I walk through the village and take a last look at the beach, the Sappho-themed commodities, the women holding hands. I think of the gift that Skala Eressos has offered: a fixed place where you can just exist. A place where you can live outside the box because the box—or the boxes, rather, that are forced upon us—does not exist here. Skala Eressos showed me what possibilities there are in a world that has so often rendered me and my community invisible and unworthy of spaces of our own. It freed me from some of my shame, and that release is perhaps the biggest gift Lesbos offered.