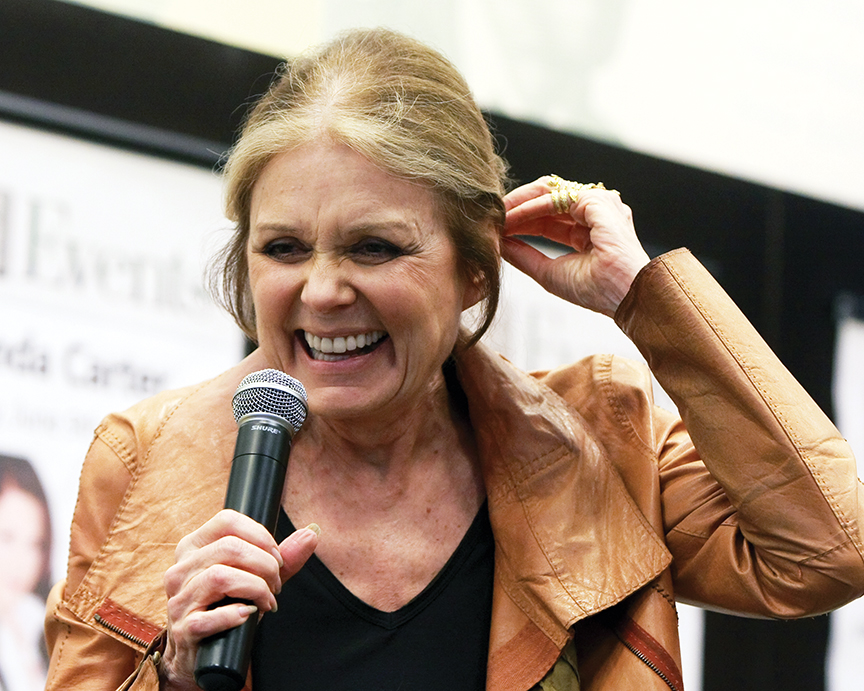

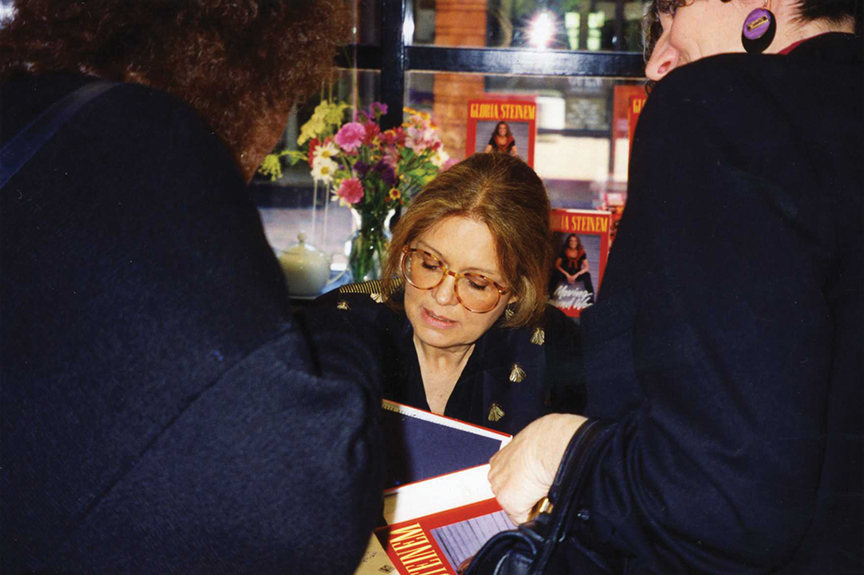

Steinem, Going Strong: The Feminist Trailblazer Reflects On The History And Future Of Feminism In This Exclusive Interview

In a candid tête-à-tête, feminist trailblazer Gloria Steinem and musician and activist Elizabeth Ziff reflect on Steinem’s ever-expanding legacy at the helm of the women’s movement, the history and future of feminism as #MeToo surges, and laughter as a measure of freedom.

Full disclosure: Gloria and I have been friends for many years. I first met her when she came to see my band BETTY in concert. I have been witness to her complete true understanding that all are equal.

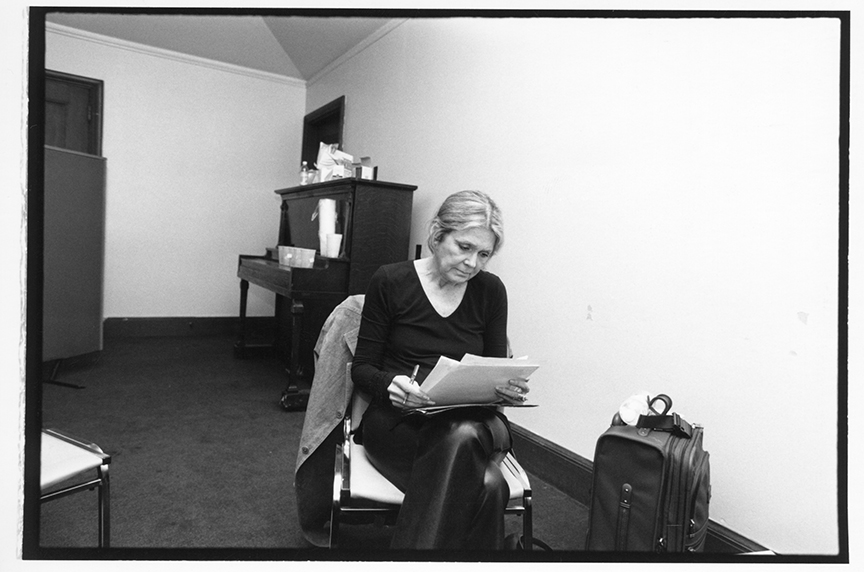

At 83, Gloria Steinem continues to work tirelessly for equal rights not only for women and girls, but also for people of all races, religions, sexual preferences and economic status. Gloria is easy to talk to, smarter than anyone I’ve ever met, has a fantastic sense of humor, and radiates hope.

In the Buddhist and Hindu belief of reincarnation, a person continues to come back and live different lives until they reach ultimate enlightenment. I believe that Gloria Steinem will not need to be reborn ever again.

I sat and had a conversation with Gloria in her New York City duplex apartment on the Upper East Side.

Elizabeth Ziff: Gloria, after everything you have seen and done and been through in your life as a feminist and as a woman, how are you not a lez? I mean, how? (laughs)

Gloria Steinem: (laughs) I mean, the same reason that you are a lez. You get born the way you get born, I think.

EZ: You don’t think anybody is skewed politically to a preference? I feel like I was.

GS: Maybe, and so maybe it’s part-way generational, because my generation was doubly skewed the other way.

EZ: When you were at Smith College, were you cognizant of the fact there were lesbians there?

GS: No, because remember, this was the 1950s.

EZ: But they existed in the ‘50s.

GS: Yes, they existed there, but [were] not really out. It was maybe literary. There was no, I’m glad to say, persecution. But there was persecution against gay men, I believe. I think the gay men on the faculty were persecuted, not by the college but by the surrounding cops and community who had a problem. I remember that.

EZ: That’s interesting. I’ve never heard you talk about that.

GS: That was not true of the very clearly lesbian, great professors like Esther Cloudman Dunn, whom I loved as a professor. I took an entire course in the literature of Shakespearean English — of which I had no interest — just because she was such a trip. She had beautiful suits and a big brooch and she called us all by our last names. She was so smart. She had a partner who was a theology professor, I think. Actually a wonderful play called “Wit” was written about her later. It’s about a woman dying of cancer who’s a professor. It was written just about her legend.

EZ: There is definitely a difference in literature now, that’s for sure.

GS: Absolutely. I think we have a long way to go, obviously, because we’re still trapped in gender. Which we made up. It’s interesting to me now at my age, too, because I’m beyond gender.

EZ: Why do you say that?

GS: Well, gender is all about reproduction, really. It’s all about getting you to do what you’re supposed to do in terms of playing a role and reproducing. It’s patriarchal, so the feminine part is definitely subservient and the others are not raising the children. But it begins to go away after 50 because that’s beyond the role.

EZ: Then how does that apply to transgender people?

GS: Transgender people have way more of a battle and a fight and difficulty in the central years of life. In older life, gender is — I don’t want to over-generalize because it depends on the individual, but gender is less important, and many women authors have written about living beyond gender and how free that is. The premise is that you’re your own self as a little girl up to say 9, 10 or 11, because you aren’t a prisoner of gender yet. Then you’re either for, against or struggling with it. Hopefully, this will go away eventually. And after 50 or 60 the best indicator of who you will be is who you were at 9 or 10.

EZ: I’m going to get into a deeper question because that’s where we’re going. I’m wondering how you think America can move forward in a progressive and enlightened way, when this country was actually built on the genocide of Native Americans and then cultivated through slavery and indentured servitude by women. It’s a light question.

GS: Well, I know we’re all dealing with this, and I would say we are inhibited from moving forward even if we don’t remember it or read about it, because, as you point out, the remnants are still with us. So we are inhibited if we don’t talk about it. I have never been to Germany, but I have the distinct impression from reading and meeting people that Germans have done a way better job of dealing with their painful past than we have. I think that every schoolchild there learns about it. We begin our history literally when Europeans came here; we don’t explain. Maybe some schools [do], but mostly we don’t explain that this was the biggest genocide in history. I mean, 90 percent of the 500 or so language groups that lived here were eliminated by war and disease. It’s still the biggest genocide in history.

EZ: We really don’t learn about it or talk about it. Or about slavery.

GS: We learn a bit more about slavery, but I fear that we don’t learn the sequel of it, and actually, those two things would help each other. For instance in Native American cultures — or at least I only really know about the Cherokee culture — they say it takes four generations to heal one act of violence. So if we are raised with violence or coercion or hierarchy or gender or racism, it’s hard to get over it and not pass on at least some of it. I do think that the idea that it takes four generations is wise.

EZ: I agree. What would you tell an LGBTQ person who identifies as a feminist now, how she or he or they would find their community? What’s the best way to get involved? GS: I don’t know if I would tell. I would listen first, because everybody’s different. I would say, “Who do you feel comfortable telling the truth to and who do you feel you’re getting the truth from?” Because that’s an internal measure, which might be more accurate than how somebody was born or what their choices are.

EZ: Yes.

GS: I would say don’t go any place you can’t laugh. Laughter is a measure of freedom.

EZ: It seems like your sense of humor has truly guided you through all of the bullshit you’ve had to deal with.

GS: I’m grateful that I had parents who were funny. My father was into terrible puns, but both my parents had a sense of humor, and it was okay.

EZ: I love reading about your parents, specifically about your father. You wrote about your mother before but you wrote more about him in this last book.

GS: Yes. I first wrote about my mother because she needed rescuing and my father, however crazy he was, lived his own life, so I didn’t feel the need to rescue him by writing about him in the same way. But I did want to write about him because I’m grateful to him.

EZ: He seems like he was fun.

GS: He was. It’s back to the generational thing. For women especially, well men, too, if you have a cruel or dictatorial or absent or an otherwise difficult father, it’s hard to know that there are good men out there. Because my father was a good guy, I realized that there were good men out there.

EZ: And lots of bad ones. Something you’ve always said was if you look into people, dictators or terrorists, homegrown or otherwise you see abuse at home and abuse they also inflicted on their wives and their girlfriends. That is their stepping stone to bigger violent acts.

GS: What drives me crazy is that it’s not out there in the media coverage, nor is it out there in a practical way to do something about it. Violence in the home is the biggest predictor of violence everywhere else and the people who go out and senselessly shoot people in the post office or the street or whatever, have almost always been in a violent home.

EZ: Why isn’t that true for women? So many women are abused and violated and have violence thrust upon them.

GS: I think because of the gender roles. What the gender roles do is they equip men to be victimizers and women to be victims. So more women who have seen violence in their homes or been abused as kids are more likely to feel they have no choice but to put up with it in later life, because they haven’t seen the choice.

EZ: You’ve said women of color taught you feminism.

GS: Mostly. I don’t mean entirely, but disproportionately. Way disproportionate to the population.

EZ: Who in particular formed that part of your feminism?

GS: I think in terms of sheer force, Flo Kennedy. Margaret Sloan[-Hunter], who was another one of my speaking partners.

EZ: Were they lesbians?

GS: No, Flo was not.

EZ: She would have been a good one.

GS: Yes, she would have been. Totally true.

EZ: In 1970, Kate Millett was on the track to being the spokesperson for the women’s liberation movement.

GS: Time magazine put her on the cover because of her wonderful book, “Sexual Politics.” EZ: Right, but then they pretty much destroyed her because she came out as bisexual.

GS: Which is completely ridiculous.

EZ: Then a bunch of you held a press conference. I’d like you to tell our readers about that, because I think it’s really important that young women and LGBTQ people understand that the feminist movement was inclusive of lesbians.

GS: It was disproportionately lesbians. For the same reason, in a way, it was disproportionately women of color, because you were less likely to be supported by a man, so more likely to be in the labor force to experience discrimination and to understand what was wrong.

EZ: You held Kate Millett’s hand during that press conference.

GS: Yes. I don’t know that I did it as a big political thing, I just wanted to be connected to her because it was just so wrong that the media first picked her up and said, ‘Oh, well, if she’s a lesbian, she can’t possibly be a spokeswoman for the women’s movement…’ I said, ‘Are you kidding me? Of course she can!’

EZ: Also, you were involved with Shirley Chisholm, who was the first Black woman to run for president and the first woman to run for a major party’s nomination in 1972. She was also the first Black Congresswoman elected in America. I wanted to ask you to tell the readers how that all went about. Did your group or did Shirley Chisholm decide that she should run for president?

GS: She decided. She was a little older than me, and she was already established. She was already a political figure in Brooklyn before the second-wave women’s movement. She was a loner because she had to be a loner. She had come along without movements, really. She’s a kind of miracle. I don’t know how she survived but when she declared for presidency, then Flo Kennedy and I and Brenda Feigen, a whole raft of people, were her delegates. So we ran on the ballot as delegates, pledged to Shirley Chisholm. We lost of course, but we all ran. I like to say that she single-handedly took the ‘white male only’ sign off the White House door.

EZ: How do you deal with the burnout and the constant criticism of the feminist movement—although I think it’s less now?

GS: Yes, nobody is ever again going to say to us post-Trump that the women’s movement is not necessary anymore. I think the most important thing is that we have each other, because we are communal animals as human beings. So even though there’s a lot we can accomplish by ourselves to survive and do well, we do need each other. The most important thing I would say is to make sure that you have some friends, colleagues, people you trust, however different you may be, and who support each other. I think that’s absolutely crucial. It’s also crucial just to pace yourself. I think in the earlier years of the women’s movement we burned out because we were naive. We kept thinking, “This is so unjust; surely if we just explain it to people they will want to do something about it, right?” And once you realize that this not something you’re probably going to be doing for a year or two, it’s probably a lifetime endeavor, it helps to pace yourself.

EZ: So you didn’t think it was a lifetime endeavor?

GS: No. Probably in the beginning I thought, well, I’ll do this for a while and then I’ll go back to my… I don’t know what I thought.

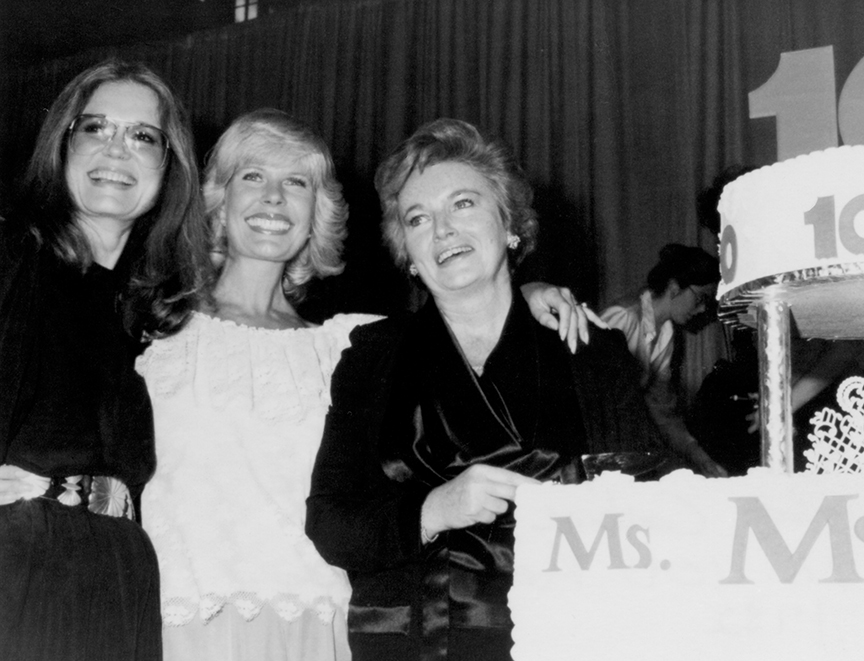

EZ: You and other great women started Ms. magazine in 1972 and put Wonder Woman on the first cover. You said it was very difficult to get the rights from DC comics, right? GS: The thing was that at that point, after World War II, she had lost all of her powers. She had turned into a carhop. She was not the Wonder Woman who was originally invented from Paradise Island with her Amazon sisters. We were partly trying to restore the original Wonder Woman, so we took the original Wonder Woman and put her on the cover — not the carhop. EZ: I think that the original Wonder Woman was definitely in the movie.

GS: Yes, I liked the movie a lot; I thought it was great!

EZ: Gal Gadot is amazing. She’s embodied the character so well. It was thrilling to watch. So if you’re reading this, Gal, thank you! Does it feel like a circle to you, from putting the stronger Wonder Woman on the cover of Ms.?

GS: Yes, I feel that we played a role, because we literally campaigned. We reprinted some of the comic strips from the golden age of the original Wonder Woman, and we literally campaigned to bring her back to herself. I remember the kind of funny Italian guy who was in charge of keeping the strip going. He called me up one day and said, “Okay, she has her magic lasso back. She has her invisible plane back. She has her bracelets back to bounce bullets off. Paradise Island is back and she has a black Amazon sister named Nubia. Now will you leave me alone?”

EZ: Ms. magazine campaigned for that?

GS: Yes. We published a whole book, actually, of the golden age strips. I wrote an introduction with Joanna Edgar, who was one of our editors and also grew up on Wonder Woman. The widow of the creator used to come in the office in her little hat and encourage us.

EZ: So Patty Jenkins, Gal Gadot and all of us have you to thank for bringing back the kickass real Wonder Woman. Thank you. You dedicated your last book, “My Life On The Road,” to Dr. Sharpe, who was the doctor in 1957 in England who referred your abortion. When I read that dedication, I burst into tears. It was so moving and sets such a tone for your book. I think if he were alive, of course he would be proud of you. Knowing firsthand how terminating your unwanted pregnancy was so important, how do you feel right now about the incredible backlash and propaganda and vitriol choking America surrounding reproductive rights?

GS: I think I know and you know and they know, our adversaries know, which is the single most important thing. All hierarchies, as far as I can see, begin with controlling reproduction. All matrilineal cultures begin with not doing that, because that means that women decide over their own bodies, so you don’t have the first step in the hierarchy. We know there’s nothing more important and they know there’s nothing more important.

EZ: Lesbians don’t live on television; they seem to be killing us off. For a long time, it seemed that whenever lesbians were on a television show or a series, the writers killed them off— at least one half of the couple. It’s really interesting that there are so few loving lesbian relationships on television series.

GS: Not even with more shows on cable?

EZ: No. We [BETTY] recently played at a conference called ClexaCon; the word is from two women who were girlfriends on a show called “The 100.” The writers killed one of them off, and people were up in arms about it. I didn’t know about this big thing, and I’d seen the show. It never even occurred to me, but there is this whole subculture of women who are desperate to see women, lesbians, on television. But every time there is a lesbian couple on television, one of them inevitably gets killed off. That’s why “The L Word” was so popular.

GS: Couldn’t “The L Word” come back?

EZ: It is coming back. It’s a reboot.

GS: You know the other thing that I think would be interesting that I haven’t seen happen is that in the same way that we’ve been urging and supporting women to just turn up for casting calls when it’s a judge or a cop or something, or the same way that now on Broadway there are a couple of plays in which one of the characters is African American, even though it’s a European play. Good actors are good actors. So maybe we should do that with couples. Heterosexual couples in plays; just two women should play it.

EZ: I’m in!

GS: That would be interesting.

EZ: The one thing I thought when I was watching “Hamilton,”— and I loved it, obviously, it’s an incredible piece of theater — is how easy it would have been to make George Washington a woman, right? Or any one of those four main characters could have been a woman. I mean none of them were Black or Hispanic in real life. So why not make one a woman. Or two?

GS: We’ve done it with race, but we haven’t quite done it with sex yet.

EZ: It would have made them queer too, because George Washington cast as a woman, would have had a wife. So we could have killed two birds with one stone, right?

GS: Have to think about that, the parent of our country.

EZ: Exactly. Whenever I hear forefathers it makes me want to cringe.

GS: I never say forefathers; I say founders.

EZ: Whenever I hear someone refer to mankind instead of humankind I automatically turn off.

GS: Right. Language is really important, I agree.

EZ: What’s always interesting to me is somebody who identifies as a lesbian but doesn’t identify as a feminist. I don’t understand it.

GS: I mourn women who don’t identify as feminists.

EZ: What do you think of the sea-change revolution, and the reckoning sought by the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, that seems to be happening after the catalyst of the Harvey Weinstein allegations?

GS: Until I was 40 or so, there was no word for sexual harassment — and it was generally seen as the fault of women for daring to be in public spaces or workplaces with men. Then, in the early 1970s, women students at Cornell University invented the phrase to describe what they were experiencing at summer jobs. Ms. reported on that as a cover story, which was banned on some newsstands as shocking, and Catharine MacKinnon defined it legally as a form of sex discrimination. Several brave Black women brought cases against the U.S. government and a bank, then also the public testimony of Anita Hill against Clarence Thomas informed the TV-watching nation that “sexual harassment” was both a phrase and a crime. I’m just saying all this because seeing how far we’ve come tells us how far we can go, especially now that millions of women — and some men, too — are speaking up and being taken seriously. That’s huge. Now we need a wave of recognizing the difference between and among men who have never been abusers, or who have been but apologize and change, and those who re-victimize women by attacking accusers, in what you might call the Trump Syndrome. We have to understand and change the reasons why 51 percent of white married women voted for Trump, a self-confessed sexual abuser, but 95 percent of Black women voted against him and for Hillary Clinton. As long as white women especially are dependent on men for economic and social identity, they’re likely to vote against themselves. This always makes me think of Harriet Tubman. Whenever she was praised for her daring trips into the South to lead slaves out to freedom, she always said, ‘I could have freed a thousand more — if only they knew they were slaves.’ Freedom begins with consciousness. Democracy begins with taking back our own voices and bodies.

EZ: What do you want your legacy to be?

GS: That’s not up to me, I don’t think. I mean…

EZ: But you can want something.

GS: That I was a good person, I guess. I don’t know. I’ve noticed in my life that I don’t know which thing that I do turns out to be important. Some little thing I did will have great impact and something I worked my heart out on will have no impact at all. So I suspect that will be true after I’m gone, too.

EZ: I don’t want you to go.

GS: I’m not — are you kidding me? I have to live past 100 just to meet my deadlines that I already have.

For more on Gloria Steinem, please visit gloriasteinem.com

Singer, musician and composer Elizabeth Ziff has performed in and written for the pop band BETTY for over 30 years. She writes for television and was a co-executive producer as well as writer on the Showtimes series The L Word. She is a freelance writer and is working on her first novel. Ziff believes in the power of women and girls and has lived her life working for equality and justice. Elizabeth is a board member and founder of the nonprofit The BETTY Effect.

hellobetty.com facebook.com/bettyverse

twitter.com/bettymusic

youtube.com/bettyverse

instagram.com/bettyrules

nonprofit:thebettyeffect.org