“Dear Queerantine” Is Building A Living Archive Of Queer Stories During Covid-19

Quarantine won’t last forever. But Dear Queerantine will live on.

As the coronavirus pandemic rages on, queer people know this strange new era by one name and one name only: “queerantine.” It may be a scary, lonely, and disorienting time, but queer people are coming up with ingenious ways to survive the ordeal, because survival is what we do best.

A new platform, lovingly titled “Dear Queerantine,” seeks to make space for queer stories during this uncertain time by building a living archive of crowdsourced stories from all around the world.

Anyone is welcome to send a (digital) letter to Dear Queerantine; in return, you’ll receive a letter from someone else in your inbox. Meanwhile, the collection of letters and stories keeps growing. Snippets are available for anyone to read through the Dear Queerantine newsletter and on social media.

The letters contain raw glimpses into the queer imagination, with stories about love, coming out, friendship, family, and so much more.

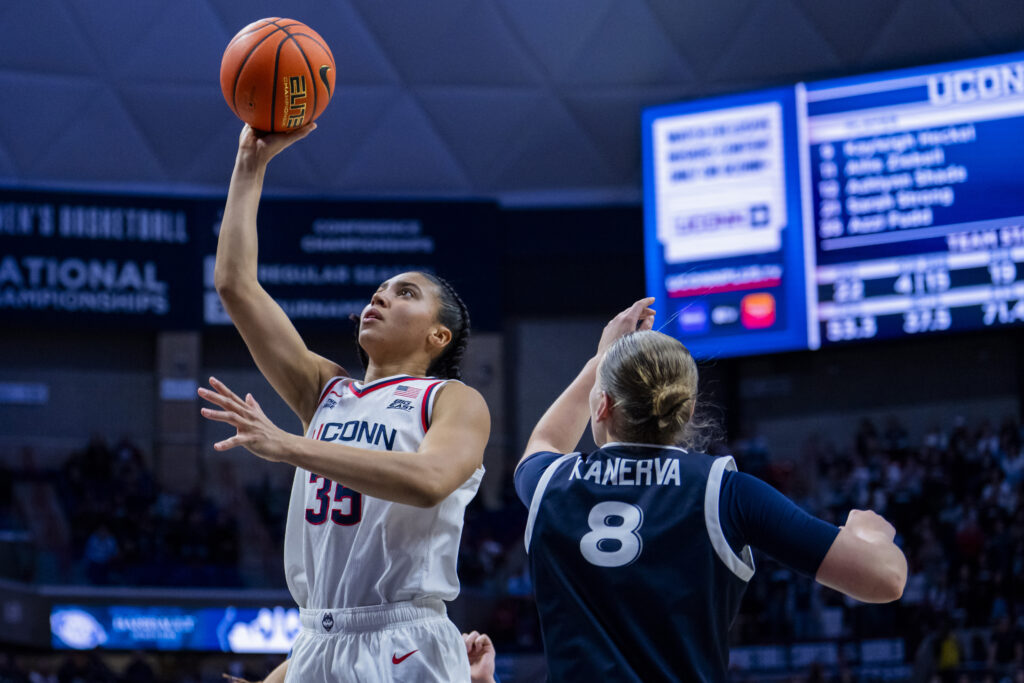

View this post on Instagram

Video journalist Meghan McDonough and data analyst Wa Sappakijjanon founded Dear Queerantine from their home in New York, the epicenter of the U.S. coronavirus outbreak. They were motivated, in part, by the dearth of dedicated spaces for queer women and non-binary people to tell their own stories.

“Representation matters, especially when so many films considered canon for us are directed by cis men,” McDonough and Sappakijjanon told GO in an email. (Films of that sort include the lesbian favorites “Blue is the Warmest Color” and “Carol.”)

By contrast, Dear Queerantine is “a living archive, written by us and for us.” McDonough and Sappakijjanon felt particularly inspired by a few recent examples of the queer female gaze in the media: “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” a Dutch mini-series called “ANNE+,” and a New York Times essay about coming out by journalist Jazmine Hughes. “All these pieces spoke to us because they were based in real feelings,” McDonough and Sappakijjanon said. “We hope others will feel the same when they share their stories and read those of others on Dear Queerantine.”

In a world where queer women remain underrepresented in history, film, TV, and even within LGBTQ+ media, storytelling is important for all queer women, no matter where they’re at in their journeys. But it can be especially life-changing for people who are just starting to come into their queerness.

Both McDonough, who grew up outside of New York, and Sappakijjanon, who is from Bangkok, know firsthand that it can be tough to come out as queer into a vacuum. Without many stories about people like you, it’s tough to make sense of fledgling feelings and desires. “Though we’re both lucky enough to have supportive communities, neither of us were exposed to many stories about queer women early on,” they said. “We had to overcome pretty significant mental and emotional hurdles to accept feelings we had.”

They added, “Desire is complicated. We’re shaped by our surroundings, and we can’t be what we can’t see. It’s hard to express what we don’t know we can feel.”

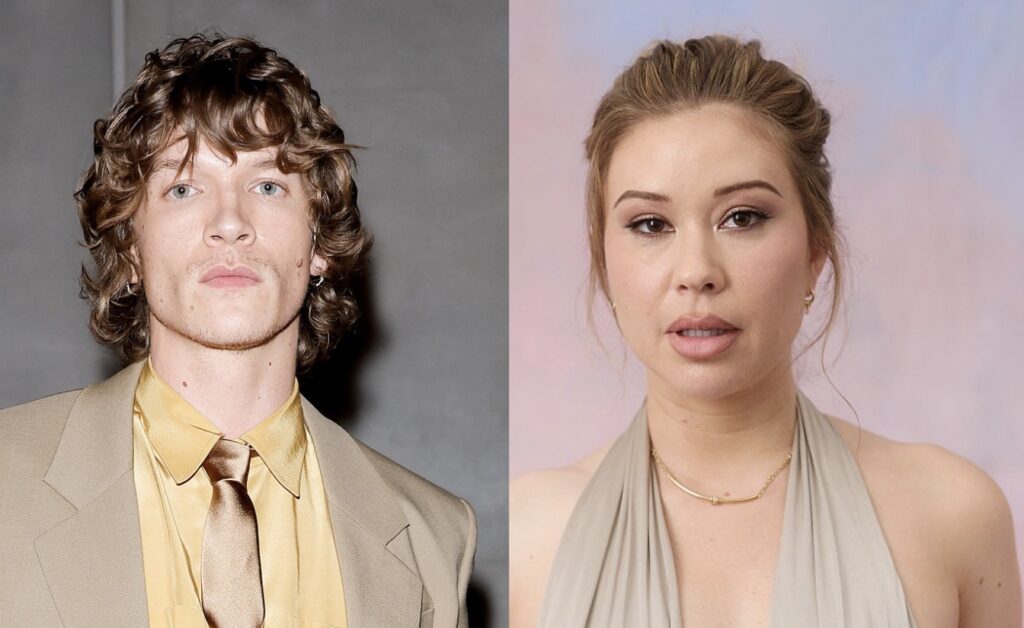

View this post on Instagram

Dear Queerantine offers more than just representation; it also offers community. Unlike a lesbian movie or book or TV show, this project requires your participation. It involves introspection, vulnerability, and connection.

For queer folks, community is everything, but it’s not always easy to access. The coronavirus pandemic has made it especially difficult for many queer people to connect with the non-blood relationships that normally keep them afloat. With Dear Queerantine, McDonough and Sappakijjanon have combined two of the best tools to help people feel grounded “in times of uncertainty and information overload:” writing and virtual community-building.

The project is still quite new, but already, the pair have received letters from all over the U.S., South America, and Asia. “Someone even messaged us from Australia asking if she could get involved,” they said. “This showed us that these experiences are universal, which reaffirms the need for this space — worldwide.” Above all, they say, the letters have been “joyful and liberating.”

“It’s honestly been a delight,” they said. “Any creative act is an invitation to play. You send it out, then you get to see what happens.”

View this post on Instagram

Quarantine won’t last forever. But Dear Queerantine will live on, even after the crisis ends. “We plan to continue collecting stories indefinitely,” McDonough and Sappakijjanon said. “We want this to become a self-generating resource and community. That could mean pen pals or however people want to connect.”

“As for what will happen to this archive long-term, that could mean anything from a book to a public art project,” they added. Because the archive is a community effort, they hope that participants will help decide upon the ultimate fate of the collection.

“For many of us, coming out felt like a confession,” McDonough and Sappakijjanon said. “Our hope is that Dear Queerantine will help people tell their stories as they want history to remember them — in all their beauty, rawness, and messy feelings.”

You can write your own Dear Queerantine letter here or read excerpts here.