The Okra Project’s Mutual Aid is Survival, Not Charity

How Executive Director Gabrielle Inès Souza and Program Director Max Rigano are scaling care for Black trans communities in a hostile climate.

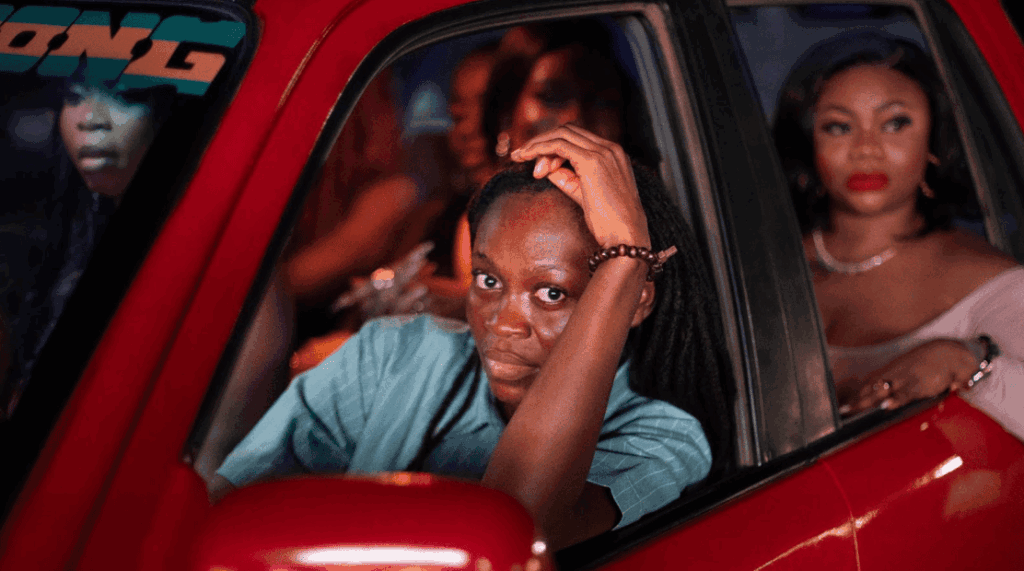

Featured Image: photo courtesy of The Okra Project.

In New York City, mutual aid is not a slogan for The Okra Project.

It is how people eat, how they get home safely, and how they find a therapist who sees them fully. The organization provides direct support to Black transgender people through meals, funding, and therapy resources.

Executive Director Gabrielle Inès Souza describes the approach in simple terms. This is solidarity, not charity. The distinction is the whole point.

“We are serving an already marginalized community within a marginalized community,” Souza tells GO. “It kind of adds a double layer to it. I speak and work from my own experience as a Black trans woman.”

Photo courtesy of The Okra Project.

Program Director Max Rigano, who is a trans man himself, adds the theory behind the practice. Charity asks people to prove they deserve help. Mutual aid starts from trust.

“Charity work is, by definition, conditional. You give me this, you jump through these hoops, you do what I need to do, and then once you prove your worthiness, Right? Who am I to determine someone’s fitness for mutual aid?” Rigano said. “It doesn’t work, because what we’re fighting against is a capitalist system [that] assigns different worth to different individuals. And really, our organization exists because not enough people find Black trans people to be worthy of the same social support systems.”

That choice shows up day to day. The Okra Project runs application windows for specific funds. Most of the fund comes from donations from the general public, with an average of $35 per donation.

People apply through a simple Google Form. The team screens out duplicates and ensures applicants meet basic criteria. Then the limits kick in. A typical cycle draws 400 to 800 requests. The funding might cover 50 people.

Related: Atlanta’s Trans Housing Coalition Steps In To Provide Much-Needed Resources

“If I could turn that 50 into 100, you can imagine the impact,” Rigano said.

Growth is the goal. Since becoming a 501(c)(3) in 2023, the Okra Project says it has delivered nearly three million dollars in direct mutual aid to almost 10,000 Black and brown trans and gender expansive people. Its programs include grocery and rental assistance, wellness stipends, and the Rides and Meals Fund.

In 2024 alone, the organization distributed $66,700 in direct mutual aid and secured $200,000 in in-kind support. Each program cycle can see up to one thousand requests. The numbers tell a clear story. Demand is high. Capacity is constrained by dollars.

Partnerships are another tool, and the team is candid about the realities. The Okra Project currently partners with BetterHelp to offer up to three months of therapy. The group previously had an in-kind partnership with Uber Eats. That formal funding ended in 2023. The Okra Project still uses Uber’s platform because it is accessible, and it lets people choose culturally specific meals and groceries. Souza is clear about vetting.

“Alignment, for me, is very important,” Souza said. “I’ve really stayed grounded in that thought process of only partnering with people who have our best interests.”

The political landscape shapes all of this. Corporate giving has cooled, and outreach has slowed, a shift that the Okra Project has felt firsthand. Earlier this year, a federal court ordered the Trump administration to reinstate $6.2 million in funding to nine LGBTQ and HIV nonprofits after attempts to cut equity and gender-affirming programs. The political climate has made it easier, Souza says, for corporations to quietly withdraw support from trans-led initiatives like Okra.

“This administration has made it much easier for corporations to be flagrant in their disinterest,” Souza said.

This is reflected in data policy, too. The failure to collect gender variance in the last census still reverberates.

“I think there’s not a lot of data collection, in general, on Black, trans and queer people, especially when we’re thinking about grassroots organizations like ours, there’s just not a lot of data out there,” Souza said. “No one’s also seeking to get data. And so I think that also creates a level of difficulty when we’re talking about policies and providing examples.”

Related: 700 Scholars, Activists and Artists Descend on NYC For Lesbian Lives Conference 2025

Rigano elaborates that the current administration is effectively erasing their community and their right to make a case for themselves.

“You can’t help people that don’t exist, right?” Rigano said.

Inside LGBTQ+ spaces, the inequities repeat. Souza remembers crowdfunding for gender affirming surgery early in her transition and not seeing recipients who looked like her.

“I think that other organizations, especially with larger followings and larger platforms, should and can do a better job at realizing that Black and brown trans people are a marginalized community within an already marginalized community, and oftentimes we are left behind in receiving the resources,” Souza said.

For her, mutual aid is personal. She describes a turning point on the way to Atlanta for surgery related to her transition. She started a fundraiser, and the community rallied. The support shifted how she saw asking for help and how she now leads.

Related: Texas Cities Face Deadline To Remove Rainbow Pride Crosswalks — And One Isn’t Backing Down

“The way that my community and people rallied for me and raised funds was just so moving and showed true solidarity,” Souza said. “Being needy in that moment and being heard because I put that need out there, really, really changed the trajectory of the way that I started to approach my own life, started to approach my own needs, and then also the needs of my community.”

Care for the caregivers is part of the job. The Okra Project is a small team, with contractors who step in as needed. Burnout is real.

“I am fighting for my community while also existing in my community,” Souza said. She leans on friends and peers, checks in with contractors, and builds what she calls networks of deep care.

The organization still needs funding. The Okra Project wants to move from sporadic distribution to monthly support. They want to double the number of people served in each cycle. They want to build a real housing channel. The logic is simple: Solidarity, not charity. Trust, not hoops. Autonomy, not stigma.

“The work that we do here is very important to me, and it’s built in that way of realizing what I’ve missed out on and what my community is missing out on from these other larger corporate organizations,” Souza said.

Donate or learn more at theokraproject.com