It’s my five-year sobriety birthday and I’m sitting on the cliffs of a Greek island, clutching my dog, Oliver. We’re on Lefkada, my father’s birth place, and we’re sitting where the original lesbian, Sappho, supposedly died. The energy is palpable and I wonder if the sensitive Ollie (he’s my namesake and a Cancer) also feels Sappho’s spirit; I bet he does. Afterwards, my brother, his girlfriend and I take Ollie to a beach where I share that it’s my sobriety birthday. No one in my family knows when it is; most of my friends don’t either. I never celebrate my sobriety birthday. But as I feel the wind in my hair and Ollie’s fur against my body and the ocean on my skin, I allow myself to open up. I still feel shame around my addiction but for now, I give myself a break from this shame. I let myself feel the fullness of this moment: that I am aligned and I’m okay.

***

It’s just after 9/11 and I live in New York City, so the vibe is end-of-the-world (sound familiar?). I drink, only a little, for the first time and write in my journal that “I just feel so free because I can say whatever.” Then I get blackout drunk “to have a little fun – to be in a state where I wasn’t self conscious about every fucking thing.” For this deeply closeted lesbian who’s (still) stuck in her head, drinking isn’t just a little fun; it’s a revelation. It gets me out of my head, into my body, and erases the overwhelming feelings of being different and wrong.

***

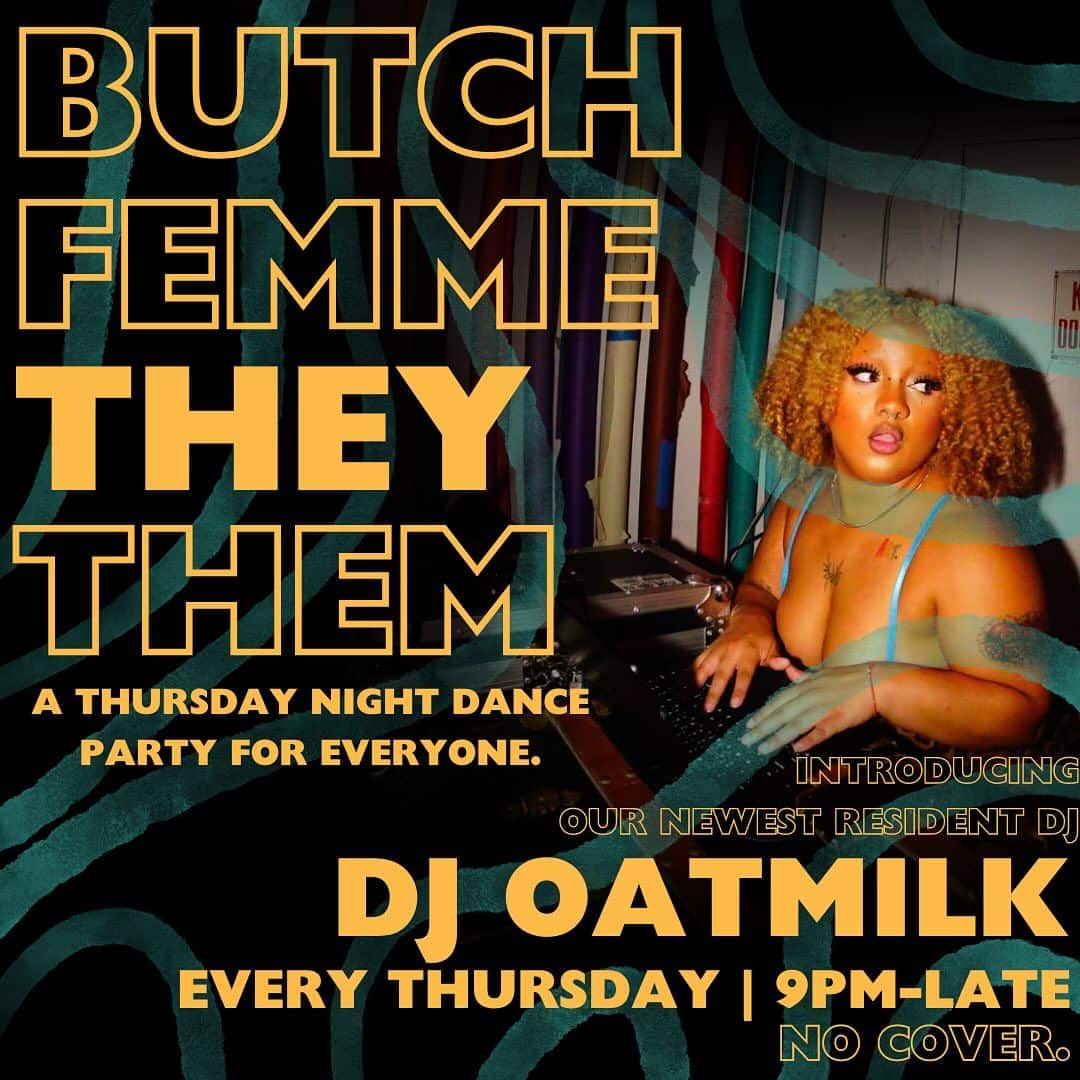

I come out as gay when I’m 22 and by this point, I’ve primarily used alcohol to erase my shame. When I come out, these self-destructive tendencies become self-celebratory as I discover sex, love, and community. The first days of my coming out are characterized by drinking, screaming, and crying on the dance floor of Akbar, a gay bar in Los Angeles. I’m ecstatic and terrified and horny all at once and I’ve never felt these sensations like this because like many queer folks, coming out aligns my mind and body as it helps me stop compartmentalizing and disassociating.

***

I’m at a glam house party in Hollywood Hills, July 2015. I’m in the pool, blackout drunk and in my underwear. When I try to get out of the pool, I fall in front of everyone, then I yell at my crush in front of her friends. I don’t remember any of this. I’m told what I did the next day by a mutual friend who wasn’t even at the party, let alone the state of California. This moment isn’t my rock bottom but it does make me ashamed enough to get sober. I quit drinking and doing drugs cold turkey and I refuse to make a sober community because that would mean my external behavior is actually tied to something internal. And I’m fine, okay? I’m totally fine.

***

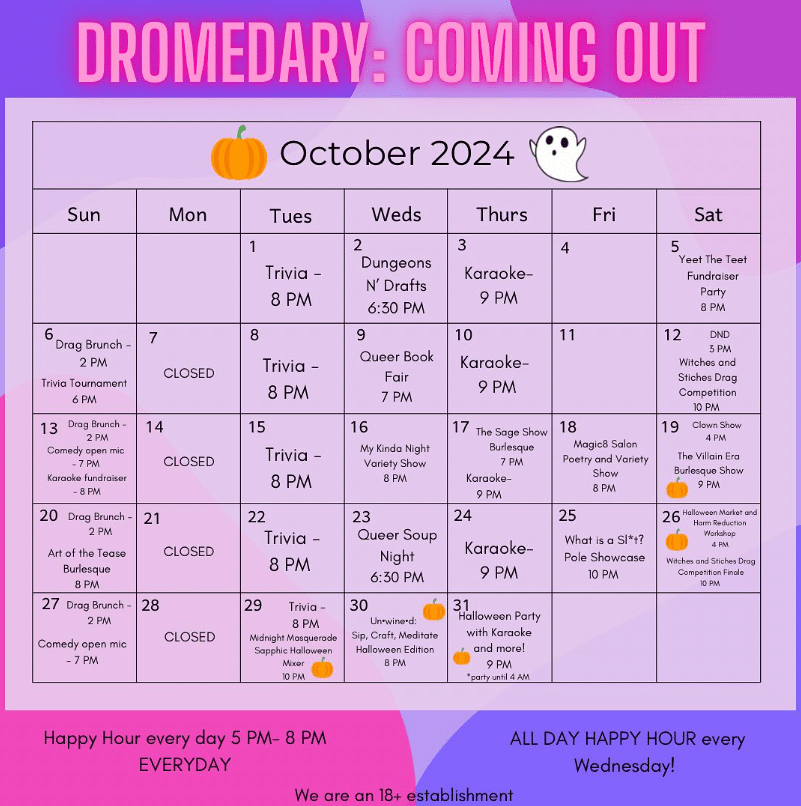

When Covid starts, I experience a collapse of time. The shame around my sobriety comes into glaring light as the pandemic triggers my addict brain, which loves having control as much as losing it; strangely, partying taps into both of those spaces. It allows me to lose control and numb the need for it while simultaneously maintaining the semblance of it by clinging onto the idea of “it’s MY body! It’s MY life!” The existential dread of the pandemic catches me on that addict’s loop of spinning out, fixating, and crawling out of my skin with anxiety. My usually minimal urges to break my sobriety increase as others go buck wild in quarantine. I wonder, if I don’t end my sobriety in a pandemic, then when?

With the loss of public spaces, I have struggled to get out of my head and into my body during Covid. Or rather, out of my shame and into acceptance. There’s a saying that guilt is the feeling that you did something wrong whereas shame is that you are wrong. When I feel aligned with myself – my mind, body and spirit – there is no shame because there’s no sense of being “wrong.” Before the pandemic, being with community was a powerful tool in sobriety to get me into that alignment.

In Covid, nature is what I have and so I go into the magical landscape of Greece constantly to find that wholeness. I frequently hike Mount Hymettus and find the most spectacular views of the Acropolis and sea (plus a mythical “dragon house,” one of the oldest buildings in Athens); I often go for sunset swims in the Aegean with my girlfriend (and sometimes Ollie); and one night, I sleep on a Greek beach under the shooting stars of the Perseids and a strip of the Milky Way nestled between the constellations of Sagittarius and Scorpio.

Communing with nature is now necessary, as my year abroad in Greece brings up shame, particularly around my sexuality (hello, closeted country) and around my substance abuse. I’m still so humiliated by some of my addict behaviors that I want to hide this part of myself from my family. Both addiction and queerness can be shrouded in shame as the messaging feels the same: there’s something “wrong” with me. So, I approach my sobriety with the same secrecy of my closeted teenage self – dealing with it totally on my own without asking for help – but Covid challenges this attitude: it’s made me realize just how much work I haven’t yet done.

I’ve been lonely in sobriety because I’ve alienated myself in it. Also, shame is super lonesome. For the first time though, I’ve realized that just cutting out my self-destructive behaviors isn’t enough. I have to cut out my shame. The shame that both led me to party and also that which marks my sobriety – and which requires an acceptance that I struggle to find on my own. I know that I have to find a sober community and surround myself with people who ask “Are you okay?” before asking “What’s wrong with you?,” much in the same way that my queer community did with my sexuality. So now, years after deciding to get sober, I’m shifting from the internal to the external and asking for help. And I’m terrified.