When GO Magazine asked me to write a piece about Cheryl Burke, I felt an ironic pang. Cheryl told me she was a lesbian in 1992. I said, “No you’re not.” I had come out the year before and was struggling with feelings of self-hatred. It was a time of “gays bash back,” when an activist group, the Pink Panthers, roamed the streets protecting queers. I didn’t want my friend to be counter-culture in an anti-gay world. Cheryl wasn’t afraid, I was.

Everyone knew her as Cheryl B, but I knew her as Cheryl. Cheryl Burke—girl from New Jersey, brilliant writer with a sharp eye for satire and relentless humor, the antithesis of the Jersey girls she depicted. We met at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She was my friend.

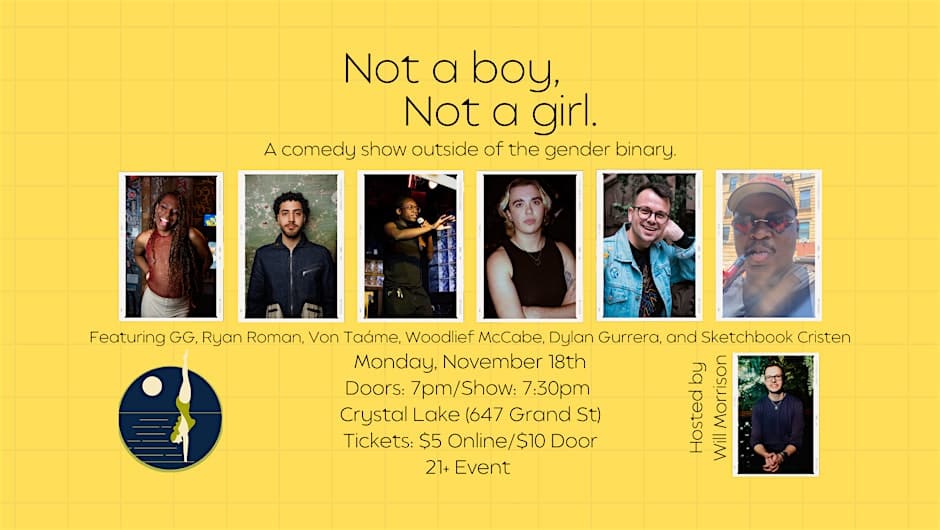

Cheryl died on June 18, 2011 of complications from the treatment of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Cheryl was an accomplished writer, with dozens of publications. She created and produced PVC: Poetry vs. Comedy Variety Show, and was the co-founder/co-host of the popular New York City monthly reading series, Sideshow: The Queer Literary Carnival with Sinclair Sexsmith. In 2011, she was named one of GO Magazine’s “100 Women We Love.” Heartbroken witness to Cheryl’s life, I offer up fragments: memories, snippets of conversation, gestures that defined her; an attempt to honor Cheryl—writer, friend, community leader and teacher—whose contributions to our culture will reach far beyond the years she was given.

Nothing stopped Cheryl from writing. Even in her final months she had her laptop at the hospital, working on articles for GO. She was a professional and she loved GO. In a visit with Cheryl shortly after she had been diagnosed, she talked at length about her work at GO Magazine and the value she placed on the relationship she had with the editors and the GO community.

Cheryl was a fearless writer. Sitting at Bluestockings, listening to her read from her memoir in progress, time crumbled for me. Her selection was set in the early nineties, our college years. “Cheryl, it’s your mother!” she said. Cheryl’s mother called multiple times a day, a category 5 enmeshment. At the time, we, Cheryl’s friends, knew about the situation. We laughed, oblivious in the way of 19-year-olds, to the pain Cheryl was experiencing. While the rest of us spent energy trying to write ourselves out of our pasts, Cheryl confronted hers. She was determined to expose the truth regardless of consequence. She made the pain accessible and bearable, using her humor to engage us. Cheryl inspired me to be a more courageous writer; to run toward what I feared most.

Shortly after college, Cheryl and I lost touch. We reconnected at a reading in 2004 and the effect on my life was dramatic. Our shared history somehow propelled our friendship past the point where we’d left off. I have never experienced this with anyone. Cheryl was extraordinary, as an artist and as a human being.

In 2008, when my father had a stroke, I sent Cheryl an email. I still remember the message she sent back. I was alone and gay in ultra-conservative Florida. Cheryl comforted me in a way that no one else could. Even if all my fears came to fruition, I had someone who got it. I had Cheryl. Cheryl took care of me. Looking back, I recognize that she took care of everyone. Kelli Dunham, Cheryl’s partner, was the first person Cheryl let care for her. When Cheryl was in the hospital Kelli never left, sleeping on the heating grate next to Cheryl’s bed. The care and constancy that Kelli gave to her started before Cheryl got sick. The night Cheryl told me about Kelli, we were at Ozzie’s in Park Slope. She smiled. “It’s good,” she said suspiciously, confounded by her happiness. That night, I saw a change in her. Cheryl felt loved.

I spoke at Cheryl’s memorial, joking that “Cheryl was not the best matchmaker.” In the nineties, she had introduced me to women with whom I had disastrous relationships. I liked to give her a hard time about it. “What were you thinking?” I said.

Cheryl looked at me and I expected a wisecrack. For all her compassion, Cheryl had a biting wit. She shrugged. “I just didn’t want you to be lonely,” she said.

Cheryl, through her generosity and intrepid examination of the world, helped me carry my burdens. I felt less alone just knowing her. I think that’s something she gave to all of us, whatever role she played in our lives. In the work she left behind, those incisive, sardonic words that unveil the things we guard, she continues to heal us. —