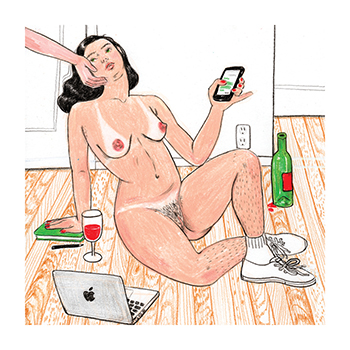

Spit and scratches. Sweat and selfies. Bruises and breasts. Blood and bikinis. Hairy legs and hot sex. Do I have your attention? Virginia Zamora sure has mine.

Virginia Zamora is a queer badass artist incorporating every deliciously sensual and uncomfortably real millennial experience into her drawings and paintings. She is an artist in every sense of the word, from the way she speaks, to the way she paints, to the way she draws, to the way she lives her life. Zamora’s career began with graphic design. Though she’s regularly drawn in her sketchbook since childhood, her illustrations weren’t public until 2017, after her work gained popularity online. When her Instagram following grew to 15 thousand and counting, Zamora’s confidence as an illustrator grew, and she became a full-time freelancer. Since then, she’s self-published a children’s book called “Hey Zoey! Get Off Your Phone!” and managed a range of commercial work, most notably a mural for Spotify’s 2018 Miami Pride celebration.

Now, Zamora continues to combine all the skills she’s acquired as a multi-hyphenated artist, entrepreneur, and creative consultant. Her last creative consultation was for Holyrad Studio’s Kickstarter and successfully raised over $50,000 for a second location. In addition, Zamora hosts and curates an annual birthday show every March featuring local New York artists and friends. Artists are not required to pay a submission fee or forfeit a percentage of sales, as Zamora feels strongly that artists need to create opportunities for other artists. She recently accepted a job as a Senior Art Director at an ad agency.

I had met Virginia on the GO float at WorldPride 2019. Okay, fine, I didn’t meet her; I just stared at her ass for 12 straight hours (so did everyone). Dressed in black pants and fishnet stockings and topped off with a full-body harness, she was definitely the highlight of our float. But beyond her gorgeous exterior was an even more beautiful mind and talent.

After seeing her first solo show “I’m Sweaty, Come Thru” at The Storefront Project, I found myself spellbound by the way she depicted femininity, pain, sex, and longing. Through a series of portraits, Zamora observes her own life and that of those closest to her. Depicting the spectrum of relationships that bleed from romantic to platonic in the queer community, Zamora paints the world as she sees it, surrounded by empowered women living in the disconnected dating reality of 2019. Hypermodern in its depictions, but flawless in its execution, Zamora’s work is the perfect balance between the perfect messiness of our lives and the imperfect meticulousness of an artist. It’s sort of the way that I want to write: edgy and deep, but accessible and raw. Looking at these jaw-dropping portraits, hearing their stories laced with lust and pain (it’s hard to decide between wanting to cry or cum), one might be shocked to learned that Zamora created and put together her first solo show in just three weeks.

I met Zamora on a brisk afternoon in Dumbo for rosé and a two-hour-long interview. She strutted in wearing a pale purple cropped tube top and mom jeans (only extremely cool people can pull off mom jeans). We talked mercury retrograde and swapped coming out stories, and she lifted the curtain to her artistic process, specifically what it was like to prepare for her first NYC solo show in only 21 days.

Virginia Zamora: Isn’t it, like, every planet is in retrograde right now?

Dayna Troisi: My prosthetic fell off when I was walking in here, and I’m like, “It’s Mercury retrograde.” It’s never fallen off my body in my life but it was like “SPLAT.” Some crazy shit is going on; it’s not your normal retrograde.

VZ: [Laughs] I felt so powerful yesterday, but then I was just, like, “feelings?”

DT: [Laughs] What’s your sign?

VZ: Pisces. That’s a very important question. What’s your sign?

DT: Leo! Were you always an artist? How did you come into yourself as an artist?

VZ: Always an artist. I used to get in trouble for drawing on top of my parents’ drawings at home. Always, always—ever since I was eight. My parents wanted me to be a dentist or a rich man’s wife, but it didn’t work out that way.

DT: And were you always interested in drawing and painting women?

VZ: My journaling started when I was around eight, and I remember my earliest drawings were my sister and I being punished for something. I would literally draw me and my sister crying, along with maybe two or three sentences about what had happened. Everything has always been very autobiographical, therefore naturally surrounding the women in my life. For a long time, it was this abstract narrative of what I was telling myself, and then it started becoming my friend’s narratives. I just felt it was more interesting to be authentic.

DT: I completely agree. That’s why I could never jive with writing fiction. It’s such a talent that I wish I had, but I’d much rather just pull from life.

VZ: Yeah, because that’s really where the meat is.

DT: Would you say you pull a lot of inspiration from your childhood, or is it more of things just happening in real-time?

VZ: You know, it’s interesting. Me and my therapist have gone over it: it’s a very acute coming of age time that I like to draw about. There’s a sweet spot when you’re 18 where it’s just, like, you’re becoming an adult. It’s probably because I left everything I knew when I was 18 to move to New York.

DT: And you were born in Miami right?

VZ: Yeah.

DT: And did you have a plan for New York or did you just, like, “YOLO?”

VZ: My parents obviously didn’t want me to come. They operate from fear and I get it. They were just like, “You’re going to get pregnant. You’re gonna fail.” And they love me, and I know they were saying that out of love. The reality is that I was terrified. I only applied to one school, the School of Visual Arts. I got in, I got financial aid, and I busted my ass.

DT: Icons only. How do you identify, and how would you say queerness informs your art?

VZ: I identify with she/her pronouns. I’ve never felt comfortable with calling myself bisexual. I also don’t like the terminology pansexual. So to answer your question, definitely queer. Feminine men excite me, masculine women excite me. I like being very masculine myself. I guess what I love about queerness is the element of play. I feel like, as artists, we’re constantly in that space where we’re questioning society. Underneath the queer label, I get to question my relationships with my platonic friends that often become sexual and then slip back into something platonic. That happens a lot in the queer community. We can also maintain relationships with people that we’ve been sexual with, and I admire that.

DT: So would you say that ebb and flow of how relationships change is part of your work? You had mentioned that you only paint and draw people you know in real life.

VZ: And sometimes it’s out of my head, completely. The last drawing I did was out of my head, but it’s a scene that I remember. It was just this man that was entertaining me and a friend and we were like, “We kind of just want you to leave.”

DT: Oh, the one with those two women with the big lips who were like “eh?”

VZ: Yeah, like, “Now? We can’t handle this.”

DT: I’m obsessed with that painting. I’m really drawn to paintings of women that intersperse modern iconography, like selfies and phones and colloquialisms and things like that. I have my MFA in poetry and I was always taught “Don’t do modern things. Don’t put a Diet Coke in your poem, no one will know that in the future.” And I was like, that’s what’s happening to me now. I think about Valfre, and Polly Nor, and Amber Carr, and all these women artists that very much represent what’s going on with women now. So I’m interested: did you have to break away from the way that you were trained at SVA? What inspired you to break rules?

VZ: School is hilarious. I did not paint the way that I paint now in school. And I was actually told all the time: “You have to do this. You have to do that. You’ll get jobs if you do this.” My senior year, I ended up getting two mentors, and it made me realize that what I need is conversations—I don’t need institutions. As far as dictating the branding and my art being influenced by 2019; again, I work from such an autobiographical place. I understand the beauty of something that is timeless, but I also understand that, for me, the greatest art form is humor. There’s nothing in humor that isn’t out of context. Everything has context. Whether it’s political, whether it’s narcissistic because of the selfie lives that we live right now, it’s important to, at least for me, incorporate into my work. I came from being an illustrator to fine arts, which means I’m essentially a storyteller. Brands are a big part of our lives. Andy Warhol and a lot of other people have pointed at that kind of iconography in the past, and those are the kinds of pieces I relate to. It’s like, oh there’s a phone there, there’s a this there. I want [my work] to definitely be a staple of my time.

DT: Can you tell us a little bit about your process, especially in regards to the huge number of paintings you created in three weeks? That f*cking blew my mind when I was looking at that.

VZ: Yeah, it was insane. I would think: What is the story I want to tell of my friend? What is the story I want to tell myself? How is it that I want the audience to feel or engage at this moment? Sometimes I take polaroids of my friends. And the important thing for me is I have to fall in love with whoever it is that I’m drawing. I have to care so deeply. If not, I can’t care about the painting. There was a moment that I wasn’t in love with the girl in the red bikini, and once I gave her the attention that she needed, I was just like, “Oh, I know what this story is.” Or, for example, in the last piece “Waiting For You To Leave,” I was having a hard time naming it. I often name before I paint, because it dictates the narrative. I name things based off conversations I hear, text messages I get; It’s interesting. And for that one, that was weird because the image informed it. I started developing it, and I was like, “Oh, my god, I’m gonna put a cigarette here.” I remember when I shifted the bottom figure’s eyes to something else—so she was glancing forward—I was like: that’s the story. We’re waiting for you to leave.

The three weeks was insane. So I essentially got the show and I was like, “I see you, Universe!” You’re f*cking out here for me, you’re looking out for me. This woman was like: “Do you want to do it in three weeks?” And I’m like, absolutely. I got into the space and had a complete breakdown. It’s huge. I know size doesn’t matter, but all my work is 6 inches by 6 inches.

I’ve always wanted to have a solo show in New York. I actually said that and wrote it in my journal every day for two months, and then I got it. And I was like, “I’ve always wanted to do big paintings!” Straight up: I got a new credit card, put myself in credit card debt, and for those three weeks, I just spent the money that I wanted to spend, created the routine that I’ve always wanted, and created the work that I’ve always wanted to create.

DT: And did you ever feel stuck? Or did you just slay under pressure?

VZ: Slayed under pressure.

DT: I can tell, and that’s just mind-boggling that you did that.

VZ: I couldn’t stop. And once I came up with a rhythm I was like, “Okay, we can do this. We’ve got this.” And then I would start working on multiples at the same time and giving each one their moment. It’s very much like a relationship.

DT: That’s so cool. I know there were a lot of skin lesions and burns and things. I know you had told me that it’s kind of like representing emotional pain in the physical, but can you talk a little bit about that?

VZ: I feel like people think that I’m definitely deep in the BDSM community. … But there’s so much emotional pain. My mom used to hit me, and I would get weirdly upset that it didn’t leave bruises. Because I didn’t think it was real.

DT: Yeah, that’s really powerful.

VZ: I used to draw on top of my skin when I was a teenager. I would put a little smear of lipstick, a little bit of green eyeshadow, and then it looked like a bruise. And it wasn’t to show off to anyone: I liked looking at it by myself at my home and being like “Oh, that happened.” And I think that so much of this 2019 culture is, like, ghost culture, getting over it, when we don’t realize the lesions, the pains, the bruises that past lovers have left us. So sometimes, we’re just reacting to pain; we haven’t taken a moment to look back at a trauma. We kind of just compress it. I also think that—my best friend Tina has highlighted this—I think that I do have a lot of rage against people that take advantage of someone’s vulnerability and someone’s openness. A lot of queer women have that narrative, especially with men, and the ways that they’ve harmed them. I’m very tough on [men], and then I have to remember that I do have male relationships in my life that haven’t harmed me. Not romantic, but platonic. And even with women as well, it’s just like everyone has their shit. I wish we could all see it.

DT: Yeah, definitely. I loved the painting of the man and he had scrat