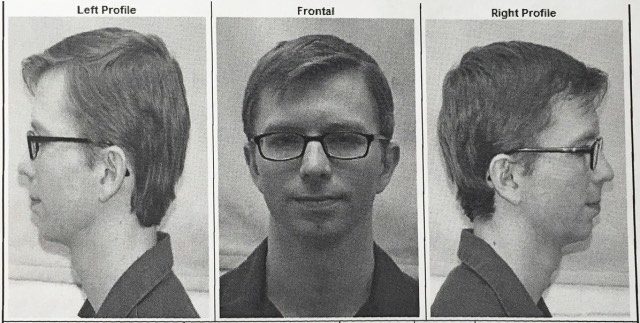

Guys We Love: Chase Strangio

Guys We Love is a feature that highlights the guys, men, boys, and bois who serve as role models in our community and allies to women and femmes alike.

“I vow to be kind and joyous and creative. I vow to dream and strive for whatever seems impossible.” Chase Strangio shared this pledge with his community on the eve of Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration. A staff attorney at the ACLU and longtime activist, Strangio has been bringing this determination and care to the fight for LGBTQ rights for years, beginning with his time as a student of history at Grinnell College, where he learned about the white supremacist origins of the country’s legal system.

“I was particularly interested in the telling of history—how we recreate historical narratives, how those narratives themselves build our systems of white supremacy, including the legal system,” Strangio said. “I never really imagined I would go to law school.”

Strangio did not initially see working within the legal system as the best way to bring about justice, but that assessment changed through his exposure to lawyers fighting to abolish the current prison system while still working within that system to protect vulnerable people.

“I started to learn more about the leadership of queer and trans people in the prison abolition movement,” he said. “I thought I would be able to contribute to movements for LGBTQ liberation by following a more radical path of lawyering in the style of the Sylvia Rivera Project.”

The Sylvia Rivera Project, where Strangio worked for several years, is a legal aid organization that serves and centers the leadership of low-income or people of color who are transgender, intersex and/or gender non-conforming.

Strangio describes a deep understanding of the legal system’s limitations while remaining committed to fighting for marginalized people within that system.

“The way we engage with the law as lawyers is always going to be reinforcing and building it. And there is also a huge demand for the work of lawyers in our community,” he said. “I’m always navigating the political idea of abolitionist work with the reformist impulse of service-based work. In the context prison advocacy and criminal defense it makes a really big different to have a lawyer versus to not have a layer but our vision cannot begin and end with legal intervention.”

Strangio is quick to describe marginalized communities’ legacy of providing for themselves outside of the systems that oppress them: from queers organizing to access life-saving healthcare traditional avenues fail to provide, to immigrants pooling money to pay criminal bail and immigration bonds for each other and sharing resources like housing, food and clothes.

“We need to keep in mind all the creative extralegal strategies for survival that have always been in place,” Strangio said. “Those should be the centerpiece of our work moving forward. Legal work is about supporting and supplementing that.”

Strangio’s ultimate vision for his work is to dismantle the systems predicated upon the exploitation of queers, trans people and people of color. And while those systems still exist, he’s fighting to give his community the best chance for survival possible. This vision is evidenced clearly in Strangio’s work as Chelsea Manning’s lawyer. In 2010, Manning, a Private First Class in the U.S. Army, leaked thousands of military and diplomatic documents containing information about U.S. military conduct in Iraq.

“She deployed to a war zone and witnessed the atrocities of war that our government was doing in our name,” Strangio said. “She wanted the public to understand. From my perspective, she shared information at great personal cost that was important for us to know, and she has faced incredibly severe consequences.”

In 2013, Manning was sentenced to 35 years in prison, the longest sentence for a whistleblower in U.S. history. “During her imprisonment, she has had to suppress her transness,” Strangio said. “She has faced harassment, denial of health care, and suicide attempts that were punished with more solitary confinement. Seven years in prison is a really long time for anyone.”

Strangio describes how Manning’s queerness and transness have deeply influenced her experiences in the military and prison.

“Chelsea was a young queer person who grew up poor and joined the military when Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was still the formal policy on gay people serving and the ban on openly trans service members was still in effect,” he said. “She joined in large part to be able to pay for an education as many people without economic security do in the United States, and also out of an abiding sense of patriotism that was fomented in a post 9/11 world.”

Since 2013, Strangio and the ACLU have been leading a broader community fight for Manning’s release. In the final days of his presidency, President Obama commuted the rest of Manning’s sentence. She is now due to be released on May 17, 2017.

“It’s been a whirlwind for her and all the people who have been working with her and known her for a long time,” Strangio said. “For now she’s just grateful that she can start to imagine a life beyond 28 more years in prison. This really is a chance for her to live, and she’s incredibly grateful for that opportunity.”

While Manning is still figuring out her plans for after her release, Strangio said continuing to fight for her community is her top priority.

“One of the things that keeps coming up is her sense of commitment and responsibility to the trans community and supporting queer and trans people who remain behind bars,” he said. “I know that she will continue to be a voice of advocacy for the community no matter where she ends up.” Strangio expects to organize financial, emotional and professional support for Manning from her community as her release date approaches.

For both Manning and Strangio, the fight continues. As the onslaught of anti-LGBTQ legislation sweeps across the country, Strangio and the ACLU pursue ongoing battles for LGBTQ rights. Strangio’s work includes the case of 17-year-old Gavin Grimm, whose high school barred him from the boy’s restroom because he identifies as transgender. Grimm’s case is likely headed to the Supreme Court by mid-2017.

As he looks ahead, Strangio speaks frequently and emphatically of his intersectional vision of liberation, of an LGBTQ movement that sees all struggles for justice as irrevocably linked.

“The LGBTQ movement has benefitted from so many people stepping up for us and sort of recognizing that their own liberation is tied up with ours. I just hope that, under this coming administration, the leadership in the mainstream movement really show up to fight against all of the ways in which most targeted members of our community are going to experience harm and have been experiencing harm related to their queerness and transness,” Strangio said. “I want us to do mobilizing around Medicaid and anti-immigrant policies and anti-Muslim policies as LGBTQ issues. Laws may not be explicitly anti-LGBTQ, but instead, criminalize sex work or drug use or deport people with criminal records. Those are LGBTQ issues.”

Strangio speaks passionately about his trans elders and contemporaries alike, from Marsha P. Johnson to Reina Gossett, from Dean Spade to Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst. Queer and trans art, so often an act of resistance, also buoys Strangio in his work.

“The things that keep me going really are the creativity and brilliance of the generations of queer and trans people who have established extralegal survival networks for so long,” he said, noting he has the work of trans artist Micah Bazant hanging in his office. Recently Strangio been finding motivation and inspiration in the words of Hoda Katebi, a Muslim-Iranian writer and activist who urges us to “abolish and build together” and “love our people intensely and intentionally.”

Strangio frequently chronicles his work on Medium.com, and his words there reverberate with equal parts honest grief and fierce optimism. At a time when so many marginalized people are weathering tremendous violence, Strangio holds space for our fears and despairs while urging us forward.

“We will build beautiful spaces,” Strangio wrote in one piece. “We will claim collective love; we will unrelentingly stand up for one another.”

What Do You Think?