Ezra Furman is wearing a Velvet Underground t-shirt, her black chin-length hair swoops towards her cheeks, and she leans low in her chair, almost sinking to the bottom of my computer screen. In the past, she has fronted the bands Ezra Furman and the Harpoons and Ezra Furman and the Boyfriends, but at the time of our Zoom interview, she seems eager to step out of the spotlight and just talk.

“The good news,” she says, “is that the world fucking sucks right now, and it has to change. The empire falls either now or later. We’re going to adapt by making big, important changes that could improve everyone’s lives, or we’re going to get hit so bad, and the empire falls that way. The tragedy, of course, is that the poor die first and suffer the most.”

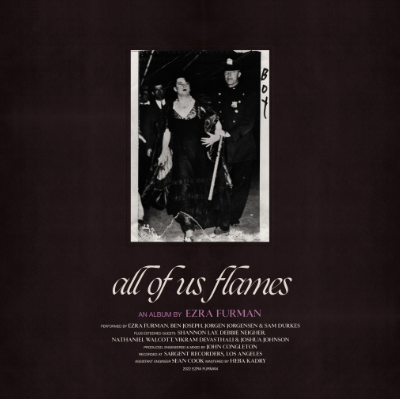

She has a thoughtful tone and parses ideas deliberately as she talks. One image bleeds into the next, the way phrases and genres from doo-wop to girl group to indie rock mutate and evolve across her albums. Her ninth album, “All of Us Flames,” released last month, is structured like a prayer.

“It opens with the universal and then zooms in. The Bible does that too,” Ezra says. “You start with the creation of the world, the fate of humanity kind of stuff. Then you have this man, this family, the specific part of the family. You get narrower and narrower until we’re talking about what kind of instruments to measure goods at the market.” It’s not incidental that the album is structured that way, Ezra–who has been taking a Talmud class at a local Rabbinical school–says. “It’s a worldview.” In prayer and writing, she says, “Establish the terms of the conversation, and then talk about what that means for how you live.”

–

Before our call, I thought about the time I first saw her perform at a student bar in Sheffield, England. I had stayed the night in a loud little hotel above a bar with Sandra, my one friend in that country. So I typed every detail of that show I could remember into Google. Google results showed a video of the show– most likely the last video taken of me as a boy, but it didn’t feel like me at all.

The video begins with the gray-green countryside of South Yorkshire rolling past a train window: wet fields, narrow canals, and sheep. It cuts to a concert. Three women–The Big Moon–play guitar on stage, and a pair of leather loafers reflects pink and purple light. Another abrupt cut. Ezra Furman, strumming rhythmically, gives the slow horizontal wave to the crowd.

There are moments where, as Sandra takes another sip of her drink and Ezra dances wildly, causing the pearls on her neck to bounce, the camera shakes and turns toward me, with short curly hair and big glasses, drunk on UV Blue, on screen for a second.

I don’t remember much of that night or that year. But I remember looking around the crowd and being surrounded, elbow-to-elbow, toe-to-heel, by other trans women for the first time in my life.

I think about the me in that moment now stuck on camera and so unaware of what would happen a month later in Brussels. How I would wake up early to catch a train from the medieval part of the city to the airport but stop when I saw an older woman drinking coffee and orange juice in the rising sun. She would be beautiful. The seconds spent watching her would cause me to miss my train and save my life.

It was March 22, 2016. I was supposed to be at the Brussels Airport when the bombs went off, but I wasn’t. I don’t like to think about it: those days, wandering around Belgium and Amsterdam. I was drunk every night and went for runs every morning. I was trying to keep my mind turned off. I was trying to keep moving. In the quiet moments of thought, I wondered if I had died, would anyone know who I was.

Furman’s songs have always followed queer characters, outcasts, and tired and desperate people with haunted heads. When I felt aimless, her songs were a compass. When I felt so disconnected from the earth that I would float away, her songs were an anchor.

When I arrived home, I sat on the bank of the Iowa River, thought about the queer people and women that surrounded me at Ezra Furman’s show that night, and knew I was one of them. I couldn’t stay static anymore. If I were going to be buried, I wanted to be buried by people who knew who I was in a body that belonged only to me.

–

“Point Me Toward the Real” comes midway through “All of Us Flames.” On it, Ezra sings, “Now, ever since I was a little child, I have felt this same old fear. / That I alone will freeze while the world proceeds / I’ll be forever stuck right here. / But I can’t live the old way. That way nearly left me dead. / I need someone new who can tell me the truth, and I don’t care who it is.”

In the three years since 2019’s “Twelve Nudes,” Ezra has come out as a transgender woman, become a mother, and provided the soundtrack for the Netflix show “Sex Education.” “It’s something I’ve said before, and I’ve heard a lot of other artists say, ‘let’s not make another [album],’” she tells me. “In 2019, I wrote a bunch of good songs, and I am still thinking about what should become of them. Some of them I gave to the hungry maw of Netflix, but it didn’t matter that they were good songs. They’re not glowing with what I need to say.”

“Then,” she tells me, “…I wrote ‘Point Me Toward the Real’ and ‘Book of our Names.’ They were like soul-talk. This is stuff I need to say, and I don’t have any other way to say it.”

Like me, Ezra kept her name when she came out. But I wonder if there is a part of us both that keeps looking back, that wants one thing and one thing only to stay the same as we careen towards a future.

“I want there to be / a book of our names,” she sings on the album’s title track. “None of them missing / None quite the same. / None of us ashes / All of us Flames.”

It’s an unknowable future, and it occurs to me that not all of us made it here. Some of us got stopped at airports or street corners, and some got stopped by police or poverty. But the system, Ezra knows, can’t last forever. “And our names will be heard,” she sings, “through prison walls, / the wet city streets / and international calls. / And we’ll read it until / this whole empire falls.”

And then, she sings, “We will continue to read it.”

In the video from years ago, the Big Moon, Ezra Furman, and I dance and bob. We will dance and bob there forever. But for now, we are living in a blessed moment I used to believe I would never live to see.

What Do You Think?