When I returned to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1972, I became Emily Alexa Freeman, my third alias, with a fairy tale for a backstory. I had one overriding rule: tell no one.

I had been convicted of four felonies for burning draft files in 1969, an act of conscience against the carnage of the Vietnam War and racism. Before the end of my federal trial, I fled with another defendant, but soon struck out on my own. It was damn risky to start over in a place where I went to college, but it was where I could be an out lesbian. Keeping my identity a secret was safer for myself and the people around me.

In a few months, I lucked into a trainee position in IT. On my secret twenty-seventh birthday, I decided to celebrate with a night out at a lesbian bar. I had a beer, ready to leave, even more bummed out than when I came in, when an athletic-looking woman offered to buy me another drink. I noticed her small breasts, trim russet hair, and neatly pressed slacks. Her name was Sherry.

After some small talk, I asked about her job. She was reluctant to answer, but I pressed her. “Is it that bad? Are you a dyke vampire?” Her reply: “I’m a military officer, part of a team on the lookout for incoming ballistic missiles.”

“Sherry, I’m a pacifist,” I couldn’t help but blurt out. She explained that a math grad who didn’t want to teach had few choices. The Air Force offered computer training and officer pay.

We couldn’t be more different, but loneliness awaited me outside. She was attractive, and I didn’t want to sleep alone that night. After a few dates, I was right that we flew in different skies. I had close gay men friends and liked to socialize with them in the Castro. Off work, she would mingle only with lesbians. She was accustomed to giving commands and following strict schedules, the farthest thing from who I was, a clandestine Berkeley grad.

But I kept seeing her, passing it off as a diversion from my “also known as” life. A few months later, I had a scary thyroid surgery (which turned out to be no big deal). Sherry took charge of my recovery and convinced me that she could do that best if I moved into her apartment.

After two trips in her Mustang, all my slim possessions were shuttled to her digs in San Francisco. Everything was planned with mathematical precision. I was under her management; her unflagging goodness was always coupled with control. I stayed on because I needed a distraction and some kind of anchor for my precarious existence. Sex with her soon became routine.

Sherry didn’t like questions or deep discussions. She rarely spoke about her drunken father. What was her childhood like in that seedy ranch house in rural Indiana? I had no standing to accuse her of being distant, as I was a fugitive cloaked in secrets.

Two years passed. She got out of the military to a good civilian job. Early in 1975, she talked me into buying a small house in the Oakland hills. The mortgage was under Sherry’s name and my alias. My signature on the closing documents was one anxious scrawl.

On the birthday of my real name, an event I couldn’t celebrate or even acknowledge, I retreated into a moody shell. That day, I was unable to bury my fear of capture, the loss of my identity, and terrible guilt for lying to her about my life before we met. I had made up a past and rationalized my dishonesty as necessary. It was too risky, plus potentially a felony to aid and abet a fugitive.

For the rest of the year, our busy domesticity was a kind of sorcery that warded off these thoughts. I could forget with her, but the price was molding to her ways. I sensed that she needed the stability that came from our commitment and settled home-life, but without understanding the source of her feelings. A taboo subject was our sex life. Strict roles in bed were a turnoff for me, but I knew not to bring it up. So, we didn’t have sex often, but we were loyal to this strange floating island. She even bought us matching gold bands.

On April 30, 1975, the Vietnam war ended with a frantic evacuation of American civilian and military personnel from Saigon. Families scrambled on crammed helicopters, shoving their children in front of them. Peace at last! My joy was mixed with a terrible sorrow for this long criminal war which had an appalling cost — millions of dead Southeast Asians and 58,000 plus American soldiers.

On that day, I remembered that I joined seventeen others to burn draft files and save lives. I had risked my liberty and entire future to protest against this slaughter. I awoke from my troubled slumber. The long, empty spell of forgetfulness with Sherry was over. It was not her fault. It was mine. She deserved to know who I really was.

A few months later, Sherry and I took a driving vacation to the Four Corners region of the Southwest. In northern Arizona on Navajo land, we signed up for a guided horseback ride to an ancient cliff dwelling ruin called Keet Seel. Bouncing for hours on a sweaty horse gave me time to figure out how to tell her. I settled on starting with the truth.

The trail wound upwards through ravines of salmon-colored sandstone. Our guide stopped at a wooden ladder rising dizzily upward to a deep shelf in the cliff. Keet Seel was a village built by people called the Anasazi, who abruptly left this place long ago.

I climbed the rungs, faltering at first. When we reached the top, Sherry and I sat on a stone wall away from the group. I drew my arm through hers, pulling her closer.

“Sherry, I’ve got to tell you something that’s been eating at me since we got together.” I took a deep breath. “I’m a fugitive because of an anti-Vietnam War action. Nothing violent, we burned draft records. I can’t say more to protect you. My real name isn’t Emily. I’m using someone else’s ID.”

Sherry didn’t flinch. “That explains some things, like why you don’t drive.”

Her first reaction was unbelievable. Avoid firestorms by sticking to practical details. I pulled my arm away, studying her face. She couldn’t look me in the eye. I saw her jaw moving, as she clenched her teeth. What was underneath that rigid exterior?

She whispered, “Your birth certificate is someone else’s?”

“Yes, but my fingerprints are all too real. I’m sorry I never told you, Sherry.”

She slid off the wall and turned to face me. For a moment, I saw scorching anger in her eyes, as I had just thrown her life into chaos. Her face turned stiff, a steely calculator frantically searching for an answer that could restore order, something she valued most.

Finally, she said, “Don’t tell me your real name or any details. The cops could try to implicate me in something. What you told me about your background, that was all bullshit, right?”

I bit my lip, nodded yes, and waited.

“Bottom line, you’re Emily to me, and all that matters is our home and life together. The only real home I’ve ever had. I don’t give a damn about the rest, so don’t bring it up again.” Sherry picked up a small rock, turning it over in her palm, then flung it over the wall below us. “It took guts to tell me. It’s time I pony up too.”

I never saw her cry before, but her eyes were now swimming in bitter waters.

She made a fist. “When I was a high school freshman, my mother killed herself. I found her in the bathroom on the floor. She shot herself in the mouth with my dad’s shotgun. No note, nothing, but I knew why. She wanted out, because my father…”

I tried to wrap my arms around her trembling shoulders, but she pulled away.

“He was a violent, fucking pig, that’s all I’ll say. C’mon, let’s see the rest of this wreck.” With that, she sidled off the wall, stretching out her hand for me.

When we returned home, we didn’t talk about our explosive truth-telling. Instead, she decided to teach me how to drive. Through her military connections, she discovered that the DMV didn’t routinely run criminal checks on fingerprints. I almost fainted when I gave the clerk mine, and again when I faced the camera for my picture.

It took another nineteen months for our relationship to implode. One Sunday morning in December 1977, Sherry said, “I’ve been sleeping with someone else for a while. You don’t know her. ” Her tone was matter of fact; her revelation appeared scripted in advance. Perhaps she thought if it sounded like no big deal, it wouldn’t be, and the ship would sail on.

The room was emptied of air. I couldn’t stand to look at her. Trust was precious, more precious than love. “You chose betrayal,” I replied icily.

“I didn’t say I was leaving. I just want to have sex with her. Let’s leave things as they are and stay together.”

“I’ve been hiding out with you, Sherry. What you suggest is no life for me.”

Her face flushed with anger. “Did you expect me to become a nun? Be an asshole! We’ll sell the house then!” Sherry banged the dining room door as she left. She was right that I lost interest in sex with her, but that story was too long off limits.

Sherry moved into the guest bedroom. So many contentious decisions followed. I moved to a studio apartment, off the floating island at last. She decided to stay at the house until escrow closed.

A month later, Sherry asked me to meet her at a downtown coffee shop. She tapped the table, her eyes shifting back and forth. “Remember what you told me at that old ruin in Arizona.”

I slowly stirred my latte, studying her face, the one I’ve kissed, the front page of her changing moods.

“I won’t tell anyone if you give me $2,500 in cash.”

A wave of panic down my spine. My brain instantly calculated the risk of her informing on me. I heard sardonic laughter in my head. What did I tell you? Never tell anyone you’re a fugitive. I was facing a potentially catastrophic lesson about trust.

I didn’t think she was a bad person. I had broken her only home, a crash and burn like her mother’s death. This was her retribution. I agreed to pay her and returned the next day with cash in a manila envelope. She said not to worry. As it turned out, she kept quiet but I never saw her again.

My escape from myself with someone else turned out to be a floating island, not solid ground. I couldn’t flee from the hard truth – the freedom I sought in going back to the Bay Area had one fatal flaw. My secrets inevitably stunted any normal relationship, and the loss of my real self was devouring my soul. But it took some time and personal courage for me to finally throw open my invisible prison.

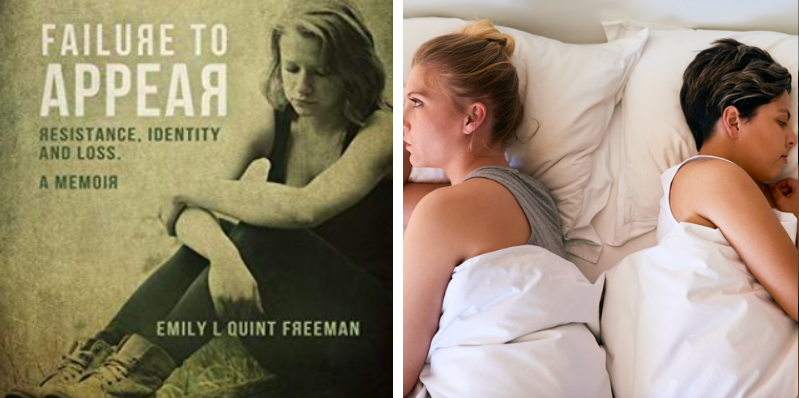

You can read my life saga from 1965 to 1989 (when I voluntarily surrendered) in my memoir, “Failure to Appear; Resistance, Identity, and Loss,” (Blue Beacon Books), published March 2020.

What Do You Think?