January 27th is International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In the 1920s, Berlin was world-famous for its queer scene, especially for having a number of drag cabaret bars. Queer people were far from equal in Germany, but they enjoyed a freedom and community prior to the Third Reich. Queer rights pioneer Magnus Hirschfeld founded the first LGBTQ+ rights organization in the world in 1897 in Berlin and also established the Institute of Sex Research in 1919 in Germany. The Institute was the largest collection of books and research about sexuality in the world before the Nazis destroyed it in 1933, and Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish men, subsequently fled Germany. The Institute had previously helped in medical advancements for groundbreaking surgeries for transgender transitions.

In concentration camps, prisoners were classified by their “crime” with different-colored inverted triangle badges: socialists wore red, emigrants wore blue, Jehovah’s Witnesses wore purple, Romani men wore brown, and so on. Jews wore two yellow overlapping triangles to form a star. Non-Jews who had helped Jews, the physically disabled, prisoners of war, military deserters, and communists were all among those persecuted by the Nazis in the camps as well.

“Homosexual men” wore pink triangles, but the exact identities of these people weren’t always known. They could have been gay men, bi men, trans women, or straight men falsely accused. Pedophiles and other sexual offenders also wore the pink triangle. It’s estimated that over 50,000 people were convicted of homosexuality between 1933 and 1944 and that only 40% of those sent to the camps survived. Exact numbers are hard to come by, but we know that thousands of people perished solely for their sexual identities during the war — likely over 10,000

The black triangle was sewn onto uniforms of various “asocial” people, including lesbians. Prostitutes, pacifists, alcoholics, the mentally ill, Romani women, and others also fit under this category. Transgender people were not officially on the list of those prosecuted, but they likely would have been classified as mentally ill and worn the black triangle.

After the liberation of the camps in 1945, homosexuality was still a crime under German law. Paragraph 175, the lines criminalizing sexual acts between men, was in effect from 1871 to 1994, so the Nazis just enforced a long-standing statute with greater severity than in other periods of German history. This meant that some queer prisoners were moved from concentration camps to regular prisons after the end of World War II, instead of being liberated.

The pink triangle, and to a lesser degree the black triangle, were reclaimed by gay activists later in the 20th century as Pride symbols. In the 1970s, the rainbow flag was created as an original symbol based in joy and celebration instead of the horrific history of the pink triangle. Still, reclaiming slurs and hate symbols is a long-standing and continuing queer tradition and the pink triangle, famously used by ACT UP, remains a powerful Pride symbol.

On this day, we remember all of the nameless queer people and all others lost during the years of the Holocaust. Several countries from Australia to Israel have erected memorials specifically to remember the gay men, lesbians, and other LGBTQ+ people who were killed for who they were and who they loved. Those monuments, seen below, serve as important physical spaces to honor those who otherwise could be forgotten.

Frankfurter Engel, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

This was the first gay-specific Holocaust memorial erected in Germany. It also recognizes the continuation of the persecution after the war. The English translation of the German inscription reads: “Homosexual men and women were persecuted and murdered in Nazi Germany. The crimes were denied, the dead concealed, the survivors scorned and prosecuted. We remember this, in the awareness that men who love men and women who love women still face persecution. Frankfurt am Main. December 1994.”

Gay and Lesbian Holocaust Memorial, Sydney, Australia

This memorial features both a pink and a black triangle and a surface that reflects light during the day and lights up at night. It is in an area known as Stonewall Gardens in Sydney’s gayborhood and is close to the Jewish Holocaust Museum. After a group of activists raised the funds for the memorial in the 1990s, it was handed over to the Sydney Pride Centre upon its dedication in 2001.

Gay and Lesbian Holocaust Victims Memorial, Tel Aviv, Israel

Standing near Tel Aviv’s LGBTQ+ community center, this concrete memorial was the first in Israel to honor both Jewish and non-Jewish Holocaust victims. The writing on the monument, which is made of three pink rectangles laying in a disconnected triangle formation, reads: “In memory of those persecuted by the Nazi regime for their sexual orientation and gender identity” in English, Hebrew, and German.

Homomonument, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

This was the first LGBTQ+ Holocaust memorial in the world, erected in 1987. It’s made of three different pink triangles spread across a plaza that are connected into one larger triangle. One triangle points towards the nearby Anne Frank House, another towards the National War Memorial, and the other towards the offices of the Dutch LGBTQ+ rights organization.

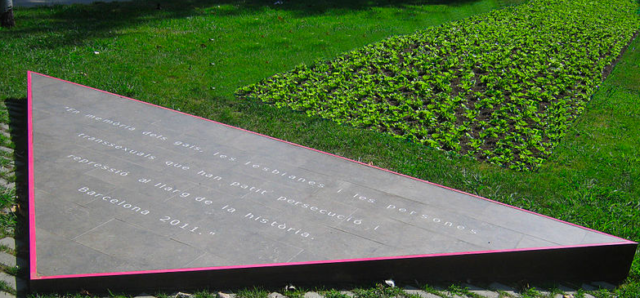

LGBT Monument, Barcelona, Spain

Unveiled in 2011 near the Catalonian Parliament, the inscription on the stone triangle monument outlined with pink metal reads in Catalan: “In memory of all the gay, lesbian and transsexual people that have suffered persecution and repression throughout history.” It is located in the Parque de la Ciudadela, in part in remembrance of Sonia Rescalvo Zafra, a 45-year-old trans woman who was murdered in that same park in 1991 by a group of skinheads.

Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism, Berlin, Germany

One of the most famous of the LGBTQ+ Holocaust memorials in the world, this is one of the only ones not to incorporate a pink triangle. The third of its kind in Germany, it was opened in 2008. The concrete cube has a hole in it, and when visitors look in, they can see a never-ending short film of two men kissing.

Memorial to Gay and Lesbian Victims of National Socialism, Cologne, Germany

Unveiled at the 1995 Pride celebration, which fell in the same year as the 50th anniversary of Germany’s liberation from Nazi rule, this memorial sits along the banks of the Rhine near a bridge where men used to cruise. The text reads in German: “Killed — Silenced: The gay and lesbian victims of National Socialism.”

Nollendorfplatz Memorial to Homosexual Victims of Nazism, Berlin, Germany

This is one of two memorials in Berlin but is considerably smaller than the one that incorporates video. The first two large words on the pink triangle affixed to a wall near a subway station read in German: “Killed. Silenced.” While it is modest, it was the first marker of its kind in the German capital.

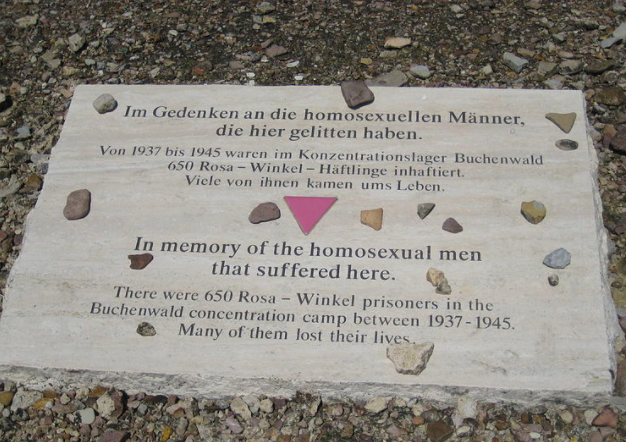

Pink Triangle Memorial, Buchenwald, Germany

Germany did not always acknowledge gay victims of the Holocaust, so this plaque at the Buchenwald concentration camp is especially significant. The inscription in German and English says that 650 pink triangle prisoners were kept at the camp from 1937 to 1945.

Pink Triangle Park, San Francisco, USA

Dedicated in 2001, this first American memorial of its kind is in the Castro district near Harvey Milk Plaza. The 15 triangular columns are arranged in the shape of a triangle inside a triangular park. An informational plaque includes a photo of concentration camp prisoners.

Too few stories of the LGBTQ+ people who died — or survived — are available or shared today. Rudolf Brazada spent three years wearing the pink triangle on his uniform in Buchenwald until the camp was liberated in 1945. When he died at the age of 98 in France, he was the last known gay Holocaust survivor to pass. His story, along with the stories of others like Josef Kohout, must not only be preserved but told. We should remember every group the Nazis deemed undesirable in the Holocaust because the oppression all of those groups then experienced continues to this day. Without understanding the history of the oppression, there is no way forward to undo it.

photos via wikipedia.

What Do You Think?